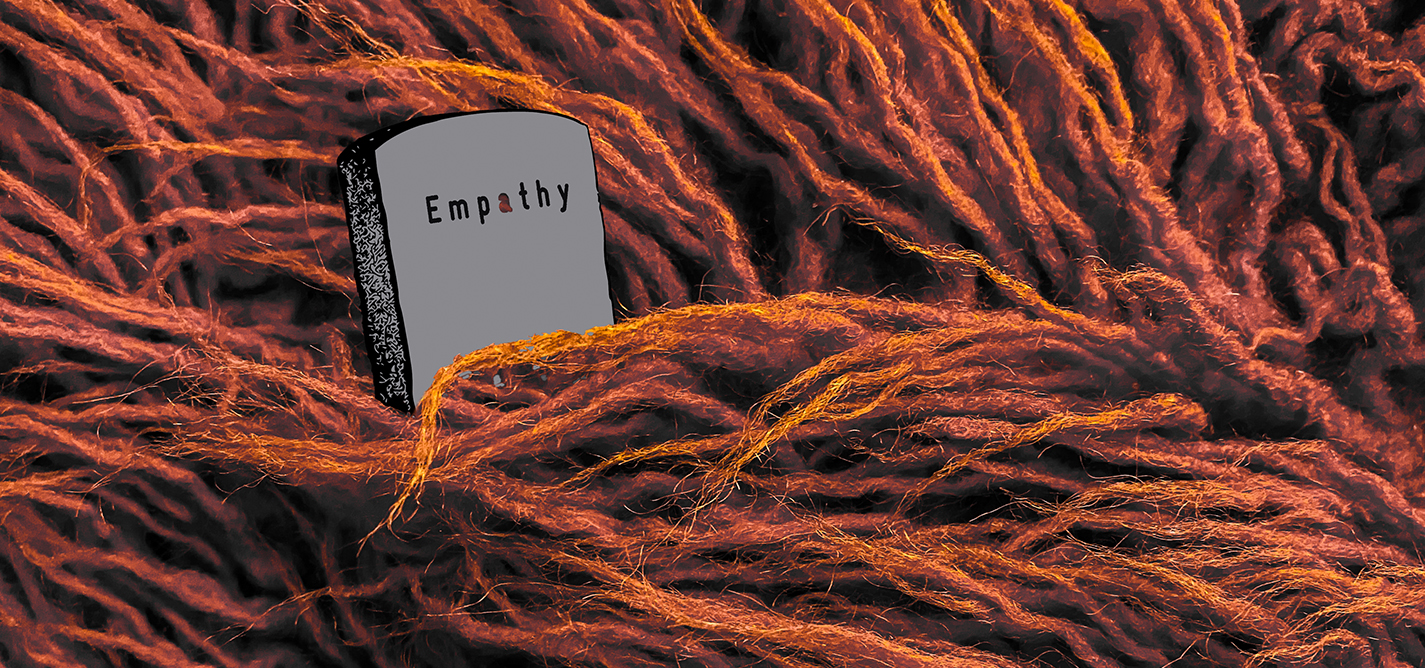

Empathy in Europe might not be only dead, but long buried

Will European leaders ever learn their lessons?

The true extent of the tragedy for those who found themselves in Turkey, of which 80% are Syrian, however, can be gleaned by the fact that they all live below the poverty line.

As refugees and asylum seekers move toward EU borders, officials respond to them as if they were a plague.

Because history doesn’t necessarily repeat itself, tragedy and farce of it aside.

Aleksandar Brezar

Aleksandar Brezar was born in 1984 in Sarajevo. Presenter and reporter for the Bosnian public broadcaster BHRT, he has also worked as a journalist at Radio 202, and on several documentaries for PBS, Holocaust Memorial Museum United States of America and Al Jazeera English. He also works as a literary translator.

DISCLAIMERThe views of the writer do not necessarily reflect the views of Kosovo 2.0.

This story was originally written in English.