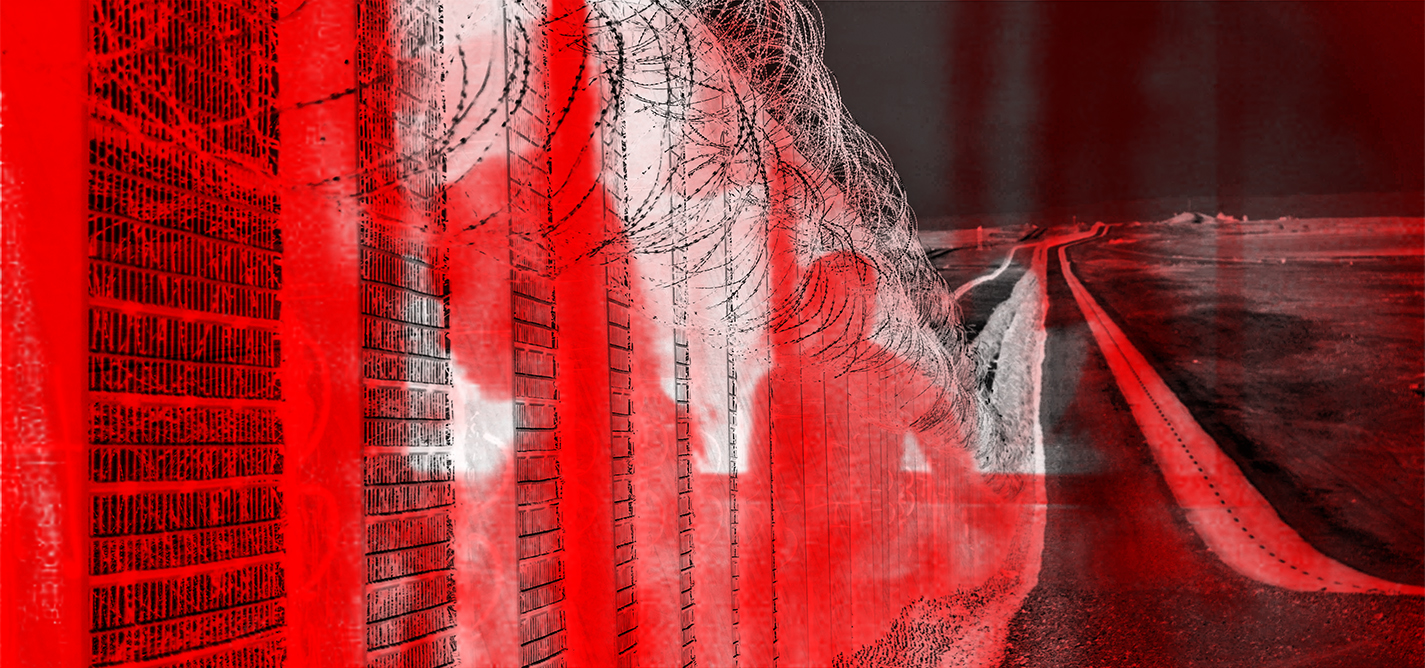

Kosovo’s battle with human trafficking

Issue prevails beneath the radar, despite improved response.

“Traffickers understood that trafficking within the country is easier and turned toward Kosovar women.”

Teuta Abrashi, Center for Protection of Victims and Prevention of Trafficking in Human Beings"A number of massage parlors have the required work permits — and massages are offered — but human trafficking cases have been identified as being behind them."

“They are traumatized and one needs to spend a good amount of time with them. At least to convince them that it is not their fault.”

Dafina Halili

Dafina Halili is a senior journalist at K2.0, covering mainly human rights and social justice issues. Dafina has a master’s degree in diversity and the media from the University of Westminster in London, U.K..

This story was originally written in English.