Walk down Prishtina’s popular kafet e vogla (‘little cafés’) drinking quarter on a Friday evening, and the idea that the lively young people spilling out onto the street from crowded bars might conform to the conservative views of their parents seems rather far-fetched. Yet contrary to standard expectations in modern society, a considerable argument exists that the young people of Kosovo are actually as conservative as the older generation, if not more so in some respects.

In a country where over half of the population of 1.8 million is under 30 years old, the attitudes of these young people towards issues like family, education, work, politics, and lifestyle are crucial indicators of the dominant future tendencies of an entire society.

A 2012 study published by NGO Friedrich Ebert Stiftung (FES) surveyed 1,000 young Kosovars aged between 16 and 27 to give an insight into their lifestyles and beliefs. “Our study has verified that there is a tendency among young people towards more conservative, traditional and religious beliefs,” said Besa Luzha, FES Program Coordinator.

The findings show that the vast majority of Kosovar youths live at home, envision themselves as married by their mid twenties (with over half wanting large families), see virginity as an important trait in a future spouse, and often turn to religion. Many of them are uncomfortable with open discussions about sex and struggle to accept homosexuality.

Kosovo 2.0 looked into the reasons why so many young Kosovars today uphold these conservative values.

Pocketmoney for sweets, and for survival

Besa Shahini, senior analyst for the European Stability Initiative (ESI), argues that the findings of the FES study are less as a result of conservatism, and more down to the strong economic reliance of young people on their family.

Socio-economic conditions in Kosovo have left a staggering 60 percent of young people aged 15 to 24 unemployed, a statistic that helps to explain why over 90 percent of respondents to the FES survey between the ages of 18 and 27 live with their parents. The majority also reported that significant, life-changing decisions were made together with their parents. Shahini suggests that a reliance on the economic and emotional support of family means that young people also have the social pressure of conforming to traditional values and conservative attitudes.

The study also found that the majority of youths surveyed envision themselves as married and creating large families of three or more children by the relatively young ages of 24 to 26, and virginity was identified as one of the most important traits to look for in a future spouse; these attitudes are firmly in line with traditional patriarchal values.

On top of these values, in modern day Kosovo it seems that economic dependence is all too often what forces young people into marriage. Shahini argues that for a young person struggling to find employment, marriage is often seen as the only way out of a reliance on economic support from parents. Even then, many continue to live with their parents or in-laws and remain dependent on their income. “They get married and begin a lifestyle that gives the impression that they have now transitioned into adulthood and independence, even though nothing has really changed,” Shahini told Kosovo 2.0.

In the 2008 ESI film “Cutting the Lifeline,” which explores the effects of independence on Kosovo’s stability, it is argued that the lack of a welfare state is replaced by solidarity with the family. Shahini, however, argues that social welfare and benefits alone would not be enough to break down the patriarchal family structures typical of Albanian society and the conservative attitudes associated with them. “To help young people gain independence, you must give them a good education and opportunities for work,” she said.

A is for apple, B is for book, C is for conservative

Improving Kosovo’s poor education system, however, is no easy task. The Kosovo Basic Education Program (BEP), funded by USAID and the Government of Kosovo, aims to address the major issues of overcrowded schools, teaching in multiple-shifts, a shortage of learning materials and equipment, disparities in education quality among municipalities, and differences in dropout rates for girls and boys and for students from ethnic minorities or with disabilities. According to USAID, the current university curriculum — specifically at the University of Prishtina — has not been modernized and is of poor quality, leaving many graduates “ill-equipped to meet today’s workforce requirements.”

“Textbooks are particularly important in Kosovo because there are no other resources for teaching,” said Shahini, who worked on a recent ESI report on education in Kosovo. “A lot of the stories and extracts included promote conservative and patriarchal values.”

She illustrates her point by describing a folk tale in a year three textbook called “I Love My Wife Like Sugar and My Mother Like Salt.” “A story about a man’s relationship with his mother and wife is not an appropriate theme for an eight-year-old, especially not when it is teaching this value that a mother is indispensable, while a wife is nice to have but not essential,” said Shahini.

Another inappropriate and conservative story from a year four textbook teaches children that if a woman is in a relationship and her fiancé leaves her, she must hide her face in public. In an article on social norms towards family and marriage, Sibel Halimi, a lecturer in the Department of Philosophy at the University of Prishtina, also points out that textbooks often reinforce traditional gender stereotypes of a woman as a housewife and a man as a figure of authority.

Linda Gusia, a sociologist at the University, argues that textbooks sometimes make conservative judgements and marginalize certain groups in society. One example is a criminology textbook, “Kriminalistika,” by Vesel Latifit, that describes women who are victims of rape or sexual harassment as “prone to lying, negligent, easily manipulated, and reckless.” The basic message that victims are actually the ones to blame sparked outrage and resulted in the textbook being banned from use at the University.

Another recent example is the year nine citizenship textbook that defined a “complete and harmonious family” as one with two parents and their children, and a “deficient and erratic family” as one without parents, with a single parent, or with children born outside of marriage. These examples highlight that all too often, patriarchal values continue to prevail.

It is clear that these textbooks are written without thought of the psychological and social consequences they may have, and that teachers, authors, publishers, and the Ministry of Education, Science and Technology (MEST) unthinkingly promote these conservative values. Halimi argues that in the absence of a professional revision, including new definitions of family and marriage, the content of these textbooks may well influence children’s personalities.

Kosovo’s weak and unreformed education system makes it easy to “plant seeds of conservatism” in the minds of children, according to sociologist Gusia. She argues that there is no open-mindedness or critical thinking, adding: “In the ’70s and ’80s there existed a belief and confidence in education. In particular, the opening of a university in the Albanian language contributed to more progressive, tolerant and open-minded views.”

A prayer for our time

Alongside the impact of poor education standards, a perceived religious resurgence is often referenced as evidence of a creeping conservatism among Kosovo’s younger generation. In a foreword for the FES study, Dr Klaus Hurrelman, Professor of Public Health and Education at Hertie School of Governance, noted that in the political and economic uncertainty of the present day, young people “resort to their religious backgrounds, sometimes even more than their parents do.”

The study found that almost all respondents belonged to a religion, usually Islam. Twenty seven percent reported that they practiced their religion on a regular basis and over half practiced occasionally.

In a 2009 essay entitled “National Identity, Islam and Politics in the Balkan,” Bashkim Iseni argued that religious revival in Kosovo is a normal change that has affected all post-communist and post-conflict countries. “The end of the communist regime and of the wars in the Albanian-populated areas in former Yugoslavia have allowed Islamic religious institutions back into the public sphere,” he said. Although as Shahini argues, the perceived increase in religious belief among young people could simply be due to more people practicing their religion openly.

In a book published in 2013, “Rediscovering the Umma: Muslims in the Balkans Between Nationalism and Transnationalism,” author Ina Merdjanova argues that politicians in Kosovo sought to redefine national identity as “modern, Western, and European” through a renunciation of Islam, citing the example of a 2003 visit of a delegation of Kosovo government officials to Germany. The female translator for the delegation, a Kosovo Albanian, insisted on wearing a headscarf. However, Merdjanova explains how “the overwhelmingly male delegation saw this as a false representation of the nation as backward, oriental and Islamist,” then cut its trip short to avoid being seen with a veiled Albanian woman.

Controversy over headscarves has also manifested in schools since 2009, when the then Education Minister, Enver Hoxhaj, banned “all religious symbols” in public schools, based on the reasoning that Kosovo is a “secular state and is neutral in matters of religious beliefs.” Over 5,000 people protested in 2010, arguing that in a country where over 90 percent of the population is Muslim, and freedom of religion is guaranteed in the Constitution, a headscarf ban was unfair. The lack of definitive legislation regarding headscarves in public schools across Kosovo has led to some schools allowing girls to wear headscarves while others ban them.

It is this sense of confusion that has led to the notion that young Kosovars today face an identity crisis. In an article for bi-monthly publication New Eastern Europe, Ida Orzechowska suggests that young Kosovars today are unable to define who they are. “Kosovars are Albanians but feel distinguished from the Albanians in Albania; they fought for independence and sovereignty, but they feel their country is run by foreign embassies,” she wrote. “Religion offers a clear identity and a sense of belonging.”

The headscarf ban sparked debate over Kosovo’s identity, and points to an entire society struggling between a politically-motivated desire to present Kosovo as “Westward-looking,” subscribing to what it sees as “European values” and a tendency towards religious practice as a support mechanism in times of political and economic uncertainty in a society that no longer restricts religious freedom.

Around the world in 80 denied visa applications

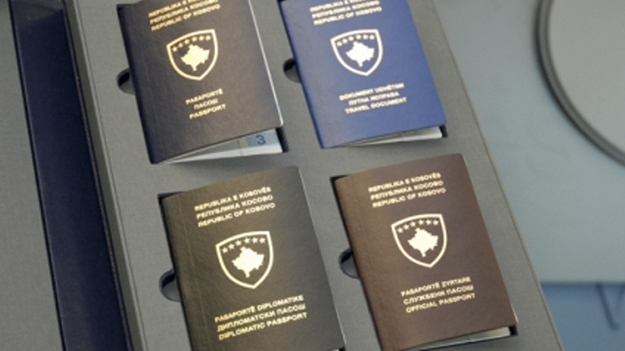

While religious freedoms have been liberalized in recent decades, freedom of movement has moved starkly in the opposite direction. Until 1991, Kosovars could travel freely throughout Europe; the Yugoslav passport was considered one of the best in the world, allowing holders global mobility. Following the breakup of socialist Yugoslavia at this time, most European countries imposed visa requirements on holders of Yugoslav passports, but Kosovars could still travel to a few dozen countries.

Today without a visa, Kosovars can only travel to Albania, Turkey, Macedonia, Montenegro, Serbia, and the Maldive Islands, making Kosovo one of the most isolated places in the world, and the last country in the region with such severe restrictions on movement.

This has created not only feelings of isolation, but also a sense of unfair treatment among young Kosovars today, who often have little exposure to different countries, societies, cultures, politics, and traditions. This could explain why many exhibit the conservative attitudes of older generations, and have not subscribed to the more progressive views of modern society.

But Shahini argues that just because young people in the 80s had family with Yugoslav passports, they did not necessarily have the means to travel: “The children of urban families in Kosovo could travel to Europe and the rest of Yugoslavia. Their children cannot today. But the rest of Kosovo, the 70 percent in the rural areas, could not travel.”

Shahini speaks of a “vicious cycle” that has driven conservatism among young people. Isolation means not only a lack of exposure to new ideas and perspectives, but also has a negative impact on an economic situation that has arguably forced young people into upholding traditional conservative views.

According to Shahini, if people had the opportunity to travel and work or study elsewhere, and then invested money or ideas in Kosovo, that would contribute to the economy. Greater integration would also help to attract foreign investment in a country which is currently isolated from the EU’s free markets, damaged by corruption and hampered by its lack of universal recognition – these conditions combine to detract potential lasting foreign investments. Under these circumstances, Kosovo cannot, for the foreseeable future, create enough jobs for the 36,000 new people entering the workforce every year, leading to mass unemployment, particularly amongst young people.

“Lost in a cloud of music and cigarette smoke”

The youthfulness of Kosovo’s population has not resulted in economic dynamism or a progressive society. The evidence points to a social condition that is not conducive to modernization and feeds conservatism. As philosophy lecturer Halimi argues: “Our society continues to struggle with conservative beliefs, insistently cultivating intolerance to certain values that developed countries treat as basic human rights.”

The phenomenon of young people displaying conservative values is not only observed in Kosovo, according to sociologist Gusia. She argues it occurs as the result of economic, political and social instability, and the rapid changes of modern life. “This uncertainty means people may revert to old-fashioned views, based on the belief that life was better back then,” she said. In her opinion, there is more safety and security in holding conservative views — it is easier to conform to a predetermined thought process than to conceive new opinions of your own.

Kosovo’s unique conditions and context seem to have accentuated this trend. Speaking in an interview for “Cutting the Lifeline,” writer and publicist Migjen Kelmendi puts it eloquently when he says: “With 70 percent of the population under 30, the whole of Kosovo can be seen as a coffee house, packed full of young people who cannot move, lost in a cloud of music and cigarette smoke.”

It is impossible to say decisively whether young people in Kosovo today are more conservative than their parents. However, there is no doubt that it will take years of economic development in order for the smoke to clear and for young Kosovars to break free from some of the conservative attitudes that patriarchal traditions and the current socio-economic environment have forced many to uphold.K