The year 2020 will, of course, be remembered for the pandemic — the fears and uncertainty, the lockdowns and restrictive measures, and the countless personal struggles and conflicts we’ve endured as we’ve sought to cope with an imposed lack of freedoms.

However, not even in times like these have the rebels across the region taken a back seat.

They have refused to give up on protesting or speaking out in public, fighting legal battles or various other forms of exercising democracy in practice — fighting for rights and liberties for all. Undaunted, they have continued to challenge those in power, seeking accountability and above all, demanding change.

In order to learn what motivates citizens across the region to take the lead in the fight against various injustices, K2.0 has identified six rebels living around us in the region. They are the people who stand firm against the many absurdities of life in the Balkans and continue the fight, often with the odds seemingly stacked against them and in the face of personal threats and abuse.

Of course, there are many more rebels, as reasons for dissent are endless. But those selected for this series represent a diverse group of individuals and issues; people who have taken one step further, mobilized others and found a way to achieve change in their respective fields.

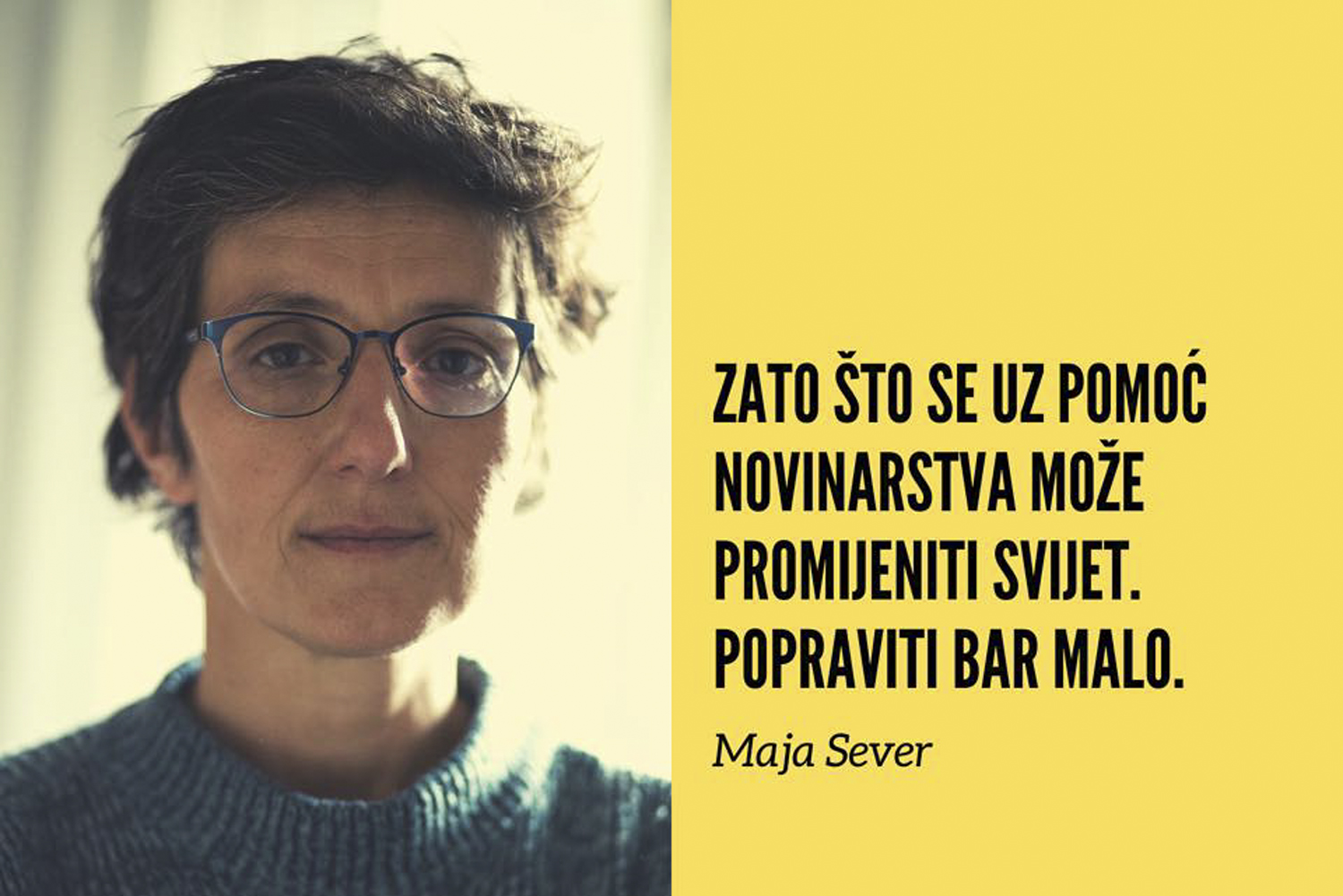

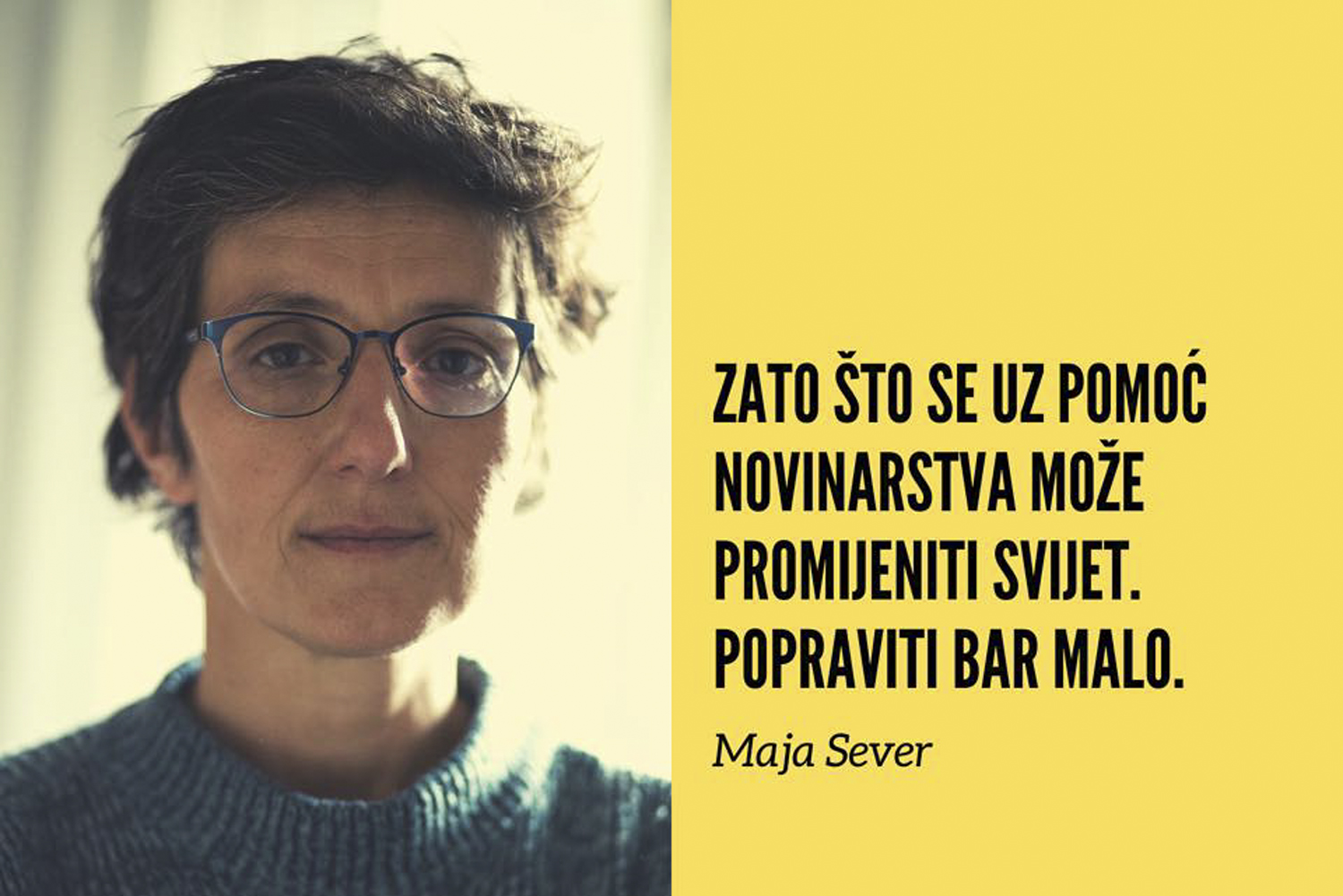

K2.0’s rebel from Croatia — with a strong motive for revolt — is Maja Sever. A journalist and TV presenter in charge of Croatia’s Trade Union of Croatian Journalists (SNH), she is known for her social involvement and dedication to freedom of speech and the media, as well as for not hesitating to speak her mind, take to the streets or help those in need through direct action.

One of the campaigns supported by Maja Sever is “Mjesto pod suncem,” (A place under the sun) a charity “for childhoods of equal opportunities.” Photo: Maja Sever private archive.

K2.0: If tomorrow you were to hold a protest that you knew would attract a lot of people and use it to draw attention to a topic you deem of major importance, what would you protest for or against?

Maja Sever: There are so many things I’d want to change! Still, I suppose one should always start from one’s own field of work, so I’d keep to the world of media and journalism.

I’m willing to put a lot of energy into the struggle for public television. I believe it’s important, no matter the fact that some of my friends or coworkers would say it’s pointless. It isn’t. Every society should fight for public television, but not with the aim to have a television licence or keep the system the way it is at all costs. It’s not that we’d take to the streets against whatever management. Instead, I think it’s worth fighting for a television model encompassing public broadcasting and a common good.

As for journalism overall, we’re in dire straits, both in Croatia and beyond. Journalists are now taking the blame for everything; they’ve become a target. Fewer and fewer people have faith in journalists, fewer people trust them. To me, restoring the trust in journalism is a significant struggle — not because we should be saving our positions or jobs, but because journalism is important in itself.

Accurate and timely information as well as investigative journalism that would bring to light malfeasances and various affairs both in politics and other walks of life are extremely important for everyone. It’s a battle we’re currently losing, even though it’s got to do with an aspect that’s crucial. It’s something I’d personally want to devote my time and effort to, something I’m willing to put loads of energy into.

What is the current state of affairs regarding public television? Your “Hrvatska uživo” program was cancelled in 2017 virtually overnight, even though it was popular.

I can’t talk about how HRT [Croatian Radiotelevision] fares business-wise since I’m still under contract with them. However, what I can talk about — and this is something no one could stop me from discussing — is my faith in the idea of public television.

All countries need public television, especially societies like ours, burdened with the past and the recent war. A public radio and television service ought to perform duties held by a public broadcaster, namely to be open to all facets of society and all social actors as well as to report on every occurrence, every politician and every party in a fair and truthful manner.

The reason why I’m still on television is precisely my faith in a public broadcasting service that’s available to everyone, a public broadcasting service that should serve everyone: A small theater in Virovitica, children with a rare disease and some local football club alike.

This idea of common good is important for me on an intimate, personal level. It’s important for me and it’s important for journalism in general. The battle for such a broadcaster continues and we shouldn’t give up on it.

In May 2019, you were elected president of the Trade Union of Croatian Journalists (SNH), an organization focused on the protection of basic labor, social and professional rights of journalists. What does the Union fight for today?

Journalists are seeing their rights grow weak, while existential and financial uncertainty directly lead to their freedoms being curtailed. As a matter of fact, in order to be able to write freely, to take a stand against all sorts of local “sheriffs” and bullies without fear, journalists should be safe and empowered.

As the president of the Trade Union of Croatian Journalists (SNH), Maja Sever advocates field work: Paying regular visits to her colleagues in other cities. Photo: Maja Sever Private archive.

The security of journalists is based on their existential security, the knowledge that they’re going to get paid, pay off the loan and feed their kids. It’s only in such a position that the journalist can be free in their journalistic pursuits.

In 2018, against the backdrop of the global financial crisis, journalists and the media scene in the country suffered a heavy blow. I think half of the journalists changed their line of work and quit journalism altogether. Since then, journalism never got back into place, neither in terms of income nor in terms of rights protection. Only two media outlets — the Croatian Radiotelevision and the Croatian News Agency (HINA) — have kept collective agreements; nine years ago, there were eleven of them. Collective labor agreements are an additional guarantee that you won’t be fired overnight, and even if you do get fired, you’ll be more protected.

We've brushed aside trade unions, their role as mediators between workers and employers, their duty to fight for workers.

On top of all this, the number of freelance journalists is growing. Employers are usually all for fixed-term employment and precarious work, for outsourcing workers and for hiring freelancers on a project-to-project basis. Meanwhile, freelancers aren’t even recognized by our law. They haven’t got access to social security or healthcare nor a guaranteed minimum income. There’s no legislation protecting them.

I think unionization is a mechanism that’s generally very important, although workers rely on it much less than they are able to. In post-communist countries, the notion of trade union and workers’ rights seems to have become somewhat of an awkward one; it’s like the term “worker” itself is now unacceptable. We’ve brushed aside trade unions, their role as mediators between workers and employers, their duty to fight for workers.

When it comes to the media scene, I think we should close ranks and change the legislation, all the while utilizing our trade union more. The aim of the Trade Union of Croatian Journalists (SNH) is to change legislation pertaining to freelance journalists and push for a national level collective agreement for all media workers, which is to serve as a guarantee for the protection of their basic rights. This is fundamental not only to our workers’ rights, but also to our vocation, our education, our freedom to write.

Precarious work is not the only issue plaguing Croatian journalism. In May, the Croatian Journalists’ Society (HND) announced that at least 905 lawsuits against media companies and journalists were underway. They warned that the purpose of those lawsuits (the so-called SLAPPs — strategic lawsuits against public participation) is to “intimidate journalists and media companies in order to have them back down from serious investigative stories.” To what extent do such lawsuits undermine media freedoms in Croatia?

The purpose of those lawsuits was exactly to exert pressure and intimidate! If a public official presses some 40 charges against a journalist or if a former minister files a dozen lawsuits against one media outlet, it sends a message.

Often, such lawsuits are not even pursued with the purpose to be won, but to wear down and intimidate the media and journalists, which eventually curbs the freedom of the press.

Maja Sever voices support for the labor rights of all media professionals and reinforces solidarity among the Union’s members. Photo: Trade Union of Croatian Journalists (SNH).

If it’s a private media outlet that isn’t publicly funded like HRT, a few legal actions could force it to shut down due to considerable legal expenses and compensations. A Šibenik-based independent news website TRIS, for example — an oasis of good reporting in that part of Croatia — had to defend themselves in court several times. In one of those instances, a Supreme Court judge sued them for making “value judgements” in a profile piece on her because she experienced “mental anguish.”

Moreover, given that funding for small non-profit media outlets like TRIS was cut back in 2016, and given that the Ministry of Culture has been stalling with the results of the European Social Fund’s call for community media financing aimed at small non-profit media organizations, it comes as no surprise that the future of a small news website like TRIS is at risk. It comes as no surprise that people are prone to self-censorship and dread writing about public officials and politicians. They’re afraid of facing charges.

This is why the SNH insists on strengthening the Media Pluralism Fund and forming a public fund for journalism. That would pave the way for funding investigative and documentary reporting, meaning that people could do investigative reporting regardless of political developments and current government composition. They could do their job. And there’s fewer of us doing this precisely due to all these issues we’ve touched upon.

Politicians would put you on the spot, too. For example, in a recent pre-election debate, Prime minister Andrej Plenković (HDZ) [the Croatian Democratic Union] mentioned you as a person who had helped the opposition to set up the debate… What does it tell us about the politicians’ demeanor toward journalists?

I found it hilarious. I couldn’t believe my ears. I think politicians only ride on the wave of distrust in the media, so they come forward in public with the claims that the media are to blame for everything or that the media accentuate a certain affair. It works like a charm.

HND and the SNH have kicked off a campaign titled “Just answer the question.” Our task is to ask a question, be it a comfortable or an uncomfortable one. The politician’s task is to answer it as our questions are of interest to citizens. We are the public voice and they ought to respect that. Throwing insults at journalists, addressing them without honorifics and by their first name or dropping remarks like PM Plenković did in the debate: It’s downright unacceptable.

Do people often object to your activism or partisanship?

Yes, people often reproach me for being an activist, although not necessarily directly.

However, I think it’s natural for every individual to rebel against injustice or anything else that’s bothering them. No one can strip me of my right to rebel against someone chopping down trees near my house just because I’m a journalist.

I can’t see how I violate the HRT’s Employee Code of Conduct or any other obligation related to journalist conduct if I protest for women’s rights or go to a march for Women’s Day. Sometimes I’d make sure not to report on a demonstration in the morning if I’m attending it in the afternoon. Although I think it would be fine even if it’s a protest held on the International Women’s Day or a protest against violence against women. I don’t believe there’s any conflict of interest, really.

Croatia was not known for people taking to the streets to demand change. Nevertheless, in the past few years, numerous protests have been organized and you would take part in them yourself. Does it seem to you that the situation is slowly changing? Are people getting more engaged?

I’ve always had the spirit of protest inside me. That’s how I was raised. I think this protest zest has been around since forever, at least in some walks of life. So, yes, I’m not sure if it’s growing. I suppose some groups of people will be protesting always — mostly in Zagreb and other bigger cities — but the problem is that there’s no one in our society who’s able to decently articulate a bigger protest. We’re very fragmented.

I’m not sure if social media has made it better or worse. I suppose it’s increased the visibility of some issues people maybe weren’t aware of in the past. On the flipside, social media scatters attention, but this doesn’t dishearten me at all.

Do you think it is possible to unite people within some sort of a wider cause, considering how divided Croatian society is?

It’s true that our society is utterly polarized […] On the other hand, although I espouse strong opinions, I’m not exclusive. I know, socialize and converse with people from the right wing. It’s not that I wouldn’t talk to some people. Do these conversations bring about dialogue, cooperation and positive change? They do.

I think we should discuss everything, but there should be a limit.

The other day, I was asked whether I knew that some people organizing the workers’ strike at Zadar’s [university] canteen — which I fully support — are right-wingers. What does it matter in this case?

I think we should discuss everything, but there should be a limit. And the limit would be to respect other people’s right to live normally and in peace.

To bring about dialogue, everyone has to make some concessions. It’s this space in between that could surely gather around people with diverging opinions who don’t want to encroach on the rights of others based on their sexual orientation, skin color or religion. We’re too small of a country not to talk to each other.

Does the dialogue, the often fruitless efforts perhaps make you exhausted sometimes?

Sometimes I’m sad, yes, because I think about how I’d love to do all sorts of things in journalism. Sometimes, when there are nasty attacks going on, when someone insults me, I get an urge to go to [the island of] Prvić and take up agriculture. However, never would I give up or get exhausted to such an extent that I’d say I couldn’t do it anymore, because I’d lose a sense of purpose. What are we if we don’t fight or try to make a change?

I live in the city center, in Zagreb. I’ve bought two pots of flowers and put them outside of my block of flats, right at the entrance. Every 20 days or so, someone takes one of them. Then I go and buy another one. I keep telling my neighbor: “You know what? I’m not backing down.” And it’s my motto in all aspects of life — including the fight for journalism or against injustice. I suppose there’s no other option.

Will you ever give up on tweeting “good morning” every day?

I didn’t even know how Twitter functioned when I made my account. I just embarked on that head on and it was great fun. Meanwhile, I’m superstitious about some things.

While I was working on “Hrvatska uživo,” I’d always take the same route to work and I’d always have the same introduction: “Good afternoon and welcome to ‘Hrvatska uživo.’ Here’s what we’ve prepared for you today.”

The audience may not have noticed, but my introduction was exactly the same for 14 years. One day, a colleague of mine wrote down the sentence with a different word order and I read it. I didn’t want to make it more complicated. Later, my dear colleague reporting live got sick. It was really stressful for me. From that point on, I never changed the introduction.

The Twitter bit falls in the same category. I’m afraid something bad would happen if I forget to tweet it!K

Feature image: Courtesy of SNH.