“We can still find happiness there. But it pains me so much… It pains me that we have great potential, and we don’t even intend to use it. So that’s why I’m leaving.”

These are the words Miloš Smolović utters on stage at the beginning of the Montenegrin version of the play “Antigona 2.0 Méditerranée”, a modern tragedy about the migration and life of young people in this small country. Smolović, along with his peers from the “Petar I Petrović Njegoš” high school in Danilovgrad, wrote the script for the play, telling their own stories, and everyday struggles.

Their literature teacher Miroslav Minić initiated the project which, along with the play, includes a documentary film and a manual for teachers under the title “Antigona 2.0 Méditerranée.” At some point, the project crossed borders, including about 80 people, mostly students, from Algeria, Morocco, Spain and Montenegro.

The endeavour was inspired by Sophocles’ drama “Antigone,” but the students gave it a new twist.

“Antigone has always been a symbol of civil disobedience,” said Minić, explaining the motive behind the project. “She is a literary character who openly inspires conflict between political power and ethical criteria, public and private life, men and women, law and morality.”

The play’s poster was designed by one of the participants, Irena Kandić.

Mediterranean dialogue

Antigone, a 5th century BC Greek tragedy written by Sophocles, follows the eponymous character as she defies the rules of Thebes’s new tyrant king Creon in order to give her deceased brother a proper burial.

Angry King Creon condemns her to death for her disobedience, but Antigone commits suicide before the execution. Creon’s son, devastated at the death of his beloved Antigone, kills himself, and then shortly after so does Creon’s wife. In her insistence on following divine laws above the corrupt laws of man, Antigone brings about the destruction of the tyrant’s family. The play’s central figure has for millenia served as a poetic exemplar of struggling for what is right.

Like Antigone, young people today have to struggle with the burden put on them by older generations. Faced with numerous obstacles, many will decide to leave their homes and become migrants, often unwillingly. Their migration changes their families, but it also affects the entire society. Many, like the actors in Podgorica, see this as a tragedy.

The Podgorica stage featured five young people. On stage, each carries a suitcase full of baggage that was packed for them by the older generation. These suitcases become a symbol of the problems and burdens of everyday life in the society where they grow up and live. But into these suitcases, the youth also manage to stow their hopes.

All the participants narrated personal stories. And such is the case with Filip Ćuković, who said that all the participants were acquainted with each other prior to the play, as they attended the same school. “But it was a basic acquaintance, just exchanging basic greetings. Only once we started opening up to each other did we realize that however much we are different from each other, we are the same in one sense, and that is that we all carry some burden, different types, and no one burden is heavier than someone else’s,” said Ćuković.

The idea for the play emerged last year in Podgorica in workshops where a group of high school students and university freshmen shared personal stories and jointly wrote a script.

According to Minić, the group got a major boost of energy once they won an award for the best original dramatic script at a high school theater competition supported by the Montenegrin Ministry of Education.

The participants of the Montenegrin play “TERET – Antigona 2.0 Méditerranée.” Miroslav Minić, Filip Ćuković, Nikolina Dobre, Vasilije Marunović, Miloš Smolović, Anja Janković, and Petar Drljević. Photo: courtesy of Una Jovović.

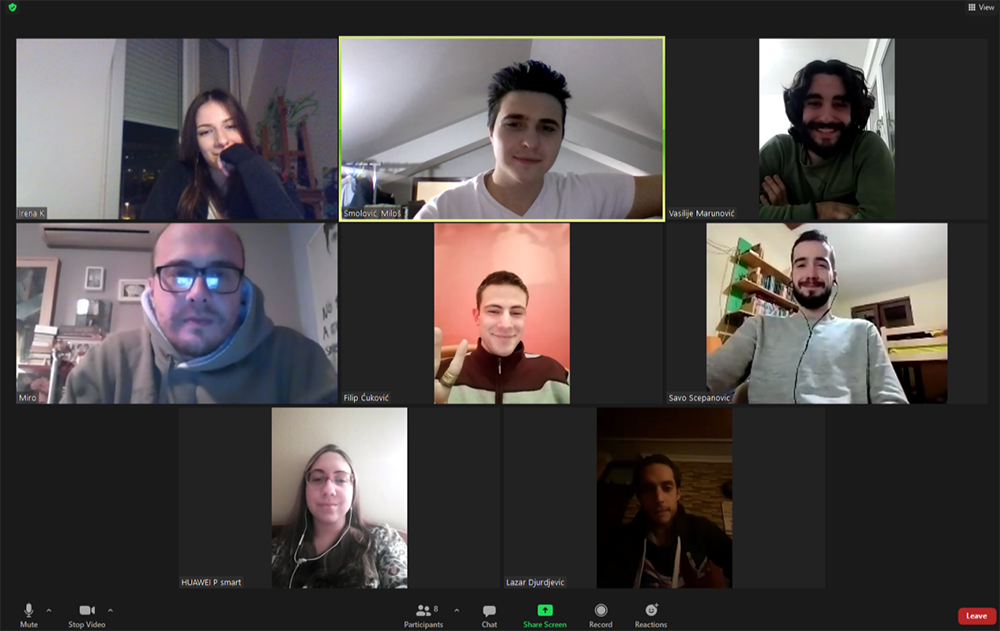

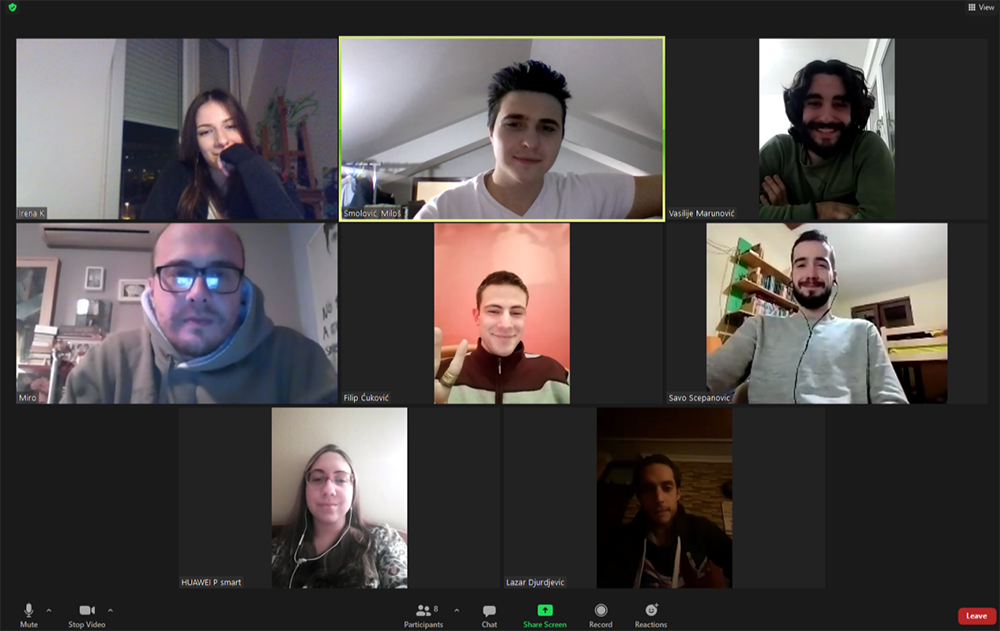

But the pandemic would be a severe obstacle for them. Online classes followed, and the rehearsals moved from the stage and classroom to Zoom.

Despite everything, the first live performance took place in September 2020 in Podgorica, at the Festival of International Alternative Theater.

This year, the project spread to cities in Spain (Valencia), Morocco (Nador, Asilah and Rabat) and Algeria (Oran). A performance was being prepared in Beirut, Lebanon as well, but a national crisis last year prevented the participants’ further work.

“We wanted for the theater to be used as a means of dialogue among Mediterranean youth, on the basis of a universal classic,” Minić said about his initial idea, which Spanish teacher Maria Kolomer Pache later joined in on.

With support from the Mediterranean Citizens’ Assembly Foundation (FACM), they were able to extend the project to other Mediterranean countries and involve more young people.

Numerous challenges

In Podgorica the students engaged in a group reading of Sophocles’s classic work and interpreted the text together through the prism of their daily lives.

“I asked the students to talk about their personal experiences, to openly discuss injustice, suppression of freedom, peer violence, gender inequality and other modern plagues,” Minić said, “but also the problems that are most important to them, but that may seem to us older folks unimportant.”

Nothing could stop the project. Meetings, conversations and preparations for the play took place at parks. Photo: archive of Miroslav Minić.

Esma Kučukalić, of FACM, says that the whole project represents a reflection of the current reality in the Mediterranean.

“We witness what is happening in the Mediterranean: the difficulties of young participants in Algeria to continue their work due to the situation in the country, or like Morocco, where participants performed Antigone in their local dialects, which is perhaps the first time that Sophocles’s work was translated into those languages,” said Kučukalić.

Vasilije Marunović, one of the participants, says that while creating the play, participants had repeatedly expressed disparate attitudes. “But that’s the point, finding a common solution. We can say that some topics were started in on that should have been addressed in our public discourse a long time ago,” he said.

Filip Ćuković didn’t hesitate to tell his personal story, with the goal of sending a message to young people who don’t feel accepted that they aren’t alone in their struggles. “The more we discuss problems, the faster we will reach a solution,” said Ćuković.

Another participant, Nikolina Dobre, said she was emboldened to be able to talk about the problems she notices around her, of which there are many.

“Not a single one is unsolvable, but most are sufficiently complex and, to be solved, necessitate good understanding and the joint effort of a whole community,” said Dobre, adding that she and her colleagues learned that it’s necessary to “educate the youth, re-educate older people and always be open to discussion and the correction of embedded prejudices.”

Zoom encounters

The project, with its multiple plays being performed in different cities and countries at the same time, helped participants create bonds that stretched across the sea.

“We gave strength to each other,” Minić said. “I’m talking about all the countries, our Zoom conversations, and our collaboration. And I remember the process as part of a great desire to change ourselves and the world, to bond with each other and become a single, unique voice of Antigone, the voice of the Mediterranean.”

For Nikolina Dobre, cooperation with her peers from other countries was an important part of the process over the past two years.

“We had a chance to directly communicate with young people from Algeria, Oran, Valencia, and to find out not only about the problems they are facing, but to see their improvements and compare their working process with ours,” Dobre said.

Due to the pandemic, rehearsals took place on Zoom. Photo: archive of Miroslav Minić.

Neither the pandemic nor geographical distance could stop the project. The result can be seen on stages in five Mediterranean countries where Antigone 2.0 has been performed.

“I think that no one expected this to come to fruition,” Minić said.

The entire crew now hopes to soon be able to present to the whole region what they’ve done in Podgorica. Due to epidemiological restrictions, performances are still uncertain, but it’s likely that the crew will soon jump on the stage of the Faculty of Dramatic Arts in Cetinje, where they will perform in front of the students.

Parallel to the play, a documentary about the pan-Mediterranean theatrical project was shown in Podgorica, and then Valencia, Nador, Asilah, Oran and Rabat. It will soon become available to a broader audience at Mediterranean festivals such as Mostra Viva del Mediterrani and the UnderhillFest International Feature Documentary Film Festival that should take place between September 22 and 30.

Minić and Kolomer also compiled a manual about the pedagogical approach that they used while working on the play. It was published in five languages: Spanish, Catalan, Arabic, Montenegrin, and French. “The manual arose as a product of our synergy, with the desire to make it easier for all coordinators, professors, movie directors and students to present their lives in a play,” said Minić.

In the original piece, Antigone says: “I was born to join in love, not hate — that is my nature.” As part of the five plays created within this project, no single actor speaks these words, but Minić said, “We are all living it, and it wasn’t difficult for us to understand each other despite the kilometers dividing us. We were bonded by our differences, but we had a single idea, we want to change the world by changing ourselves.”

“The better future for which we hope is common, so the effort which we must undertake must be common too,” said Nikolina Dobre.

Feature image: Courtesy of Una Jovović.

This article has been produced with the financial support of the “Balkan Trust for Democracy,” a project of the German Marshall Fund of the United States and the Royal Norwegian Embassy in Belgrade. Opinions expressed in this article do not necessarily represent those of the Royal Norwegian Embassy in Belgrade, the Balkan Trust for Democracy, the German Marshall Fund of the United States, or its partners.