Police officials sued for gender-based discrimination

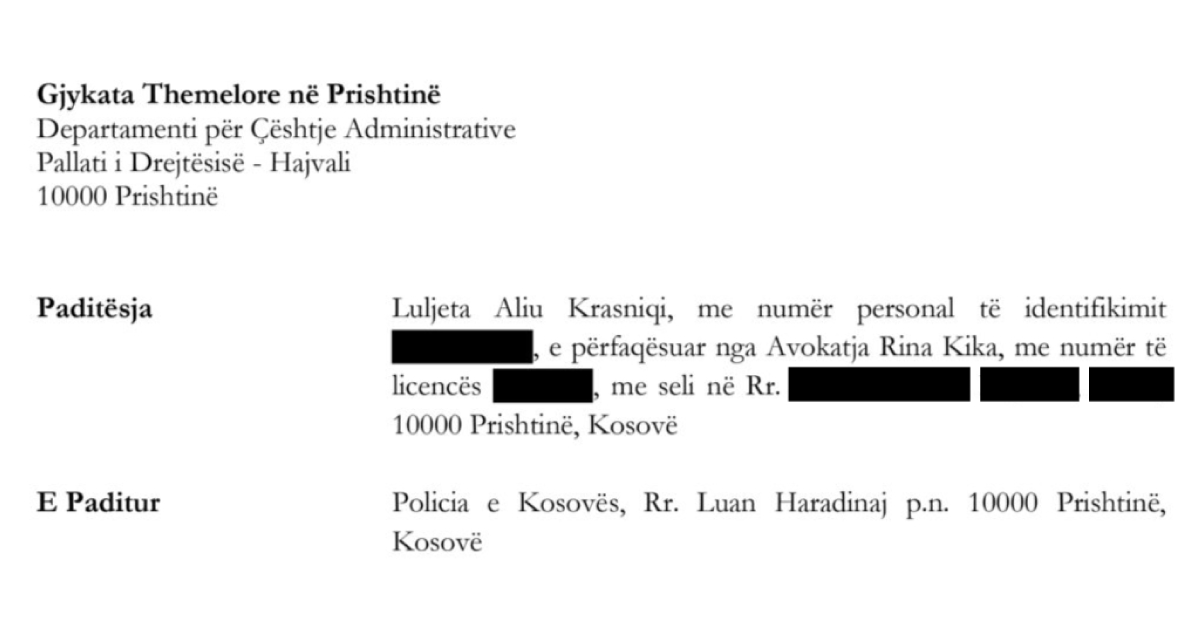

Luljeta Aliu accuses Kosovo Police of violating her rights.

"The institutions have a culture of impunity and lack transparency."

"Whenever a police officer is informed about a case of domestic violence against a woman and does not take steps to protect her from this violence, they are involved in unequal treatment."

Rina KikaFor Aliu, this treatment by police officials constitutes a complete denial of her rights.

Dafina Halili

Dafina Halili is a senior journalist at K2.0, covering mainly human rights and social justice issues. Dafina has a master’s degree in diversity and the media from the University of Westminster in London, U.K..

This story was originally written in Albanian.