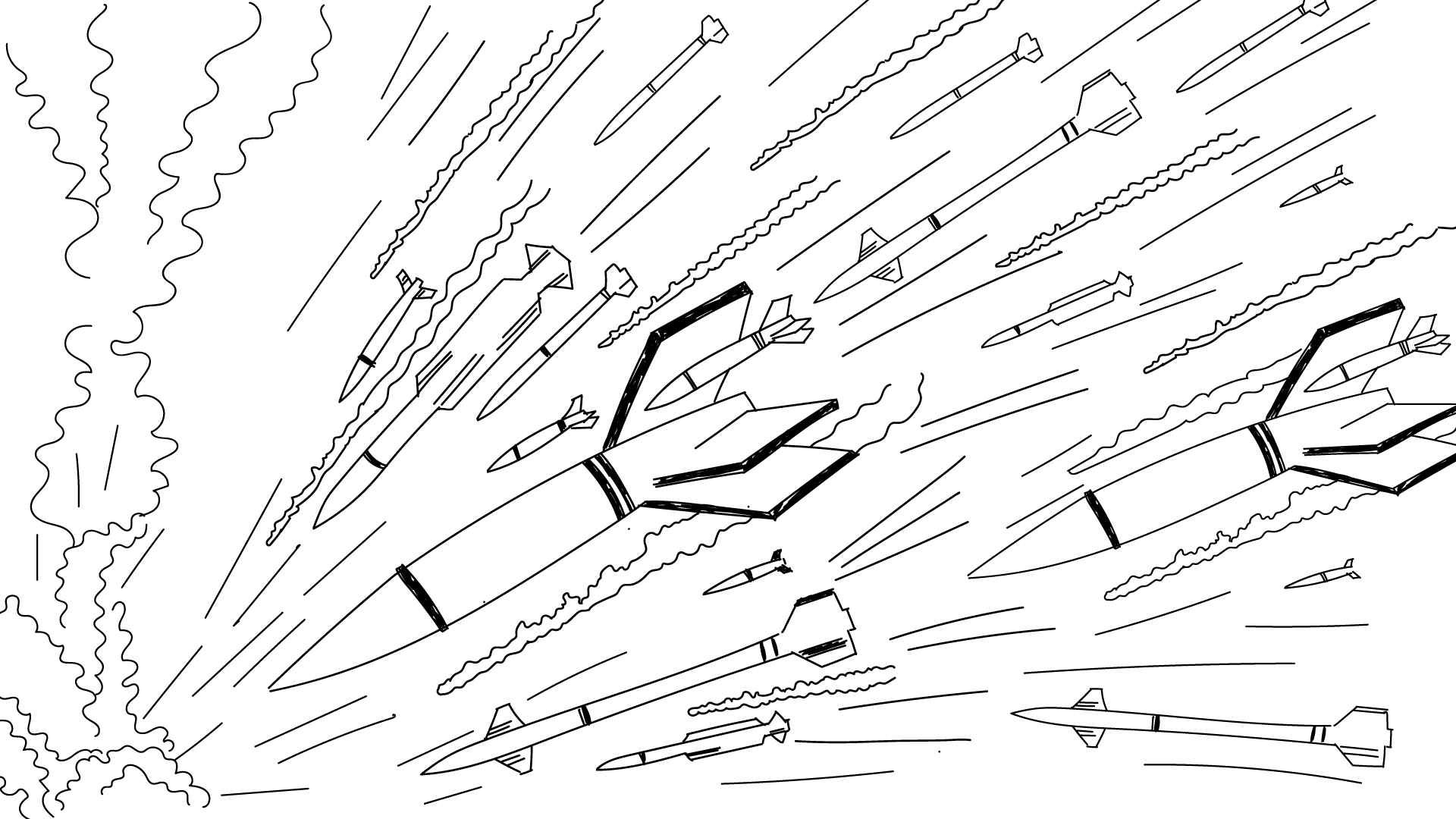

Ten stories and a poem about war

The war in Ukraine brings back the memories of another war.

Kosovo 2.0

Kosovo 2.0 is a pioneering independent media organization that engages society in insightful discussion. Through our print and online magazines, debates and advocacy initiatives, we are dedicated to deepening the understanding of current affairs in Kosovo, the region and beyond.

This story was originally written in Albanian.