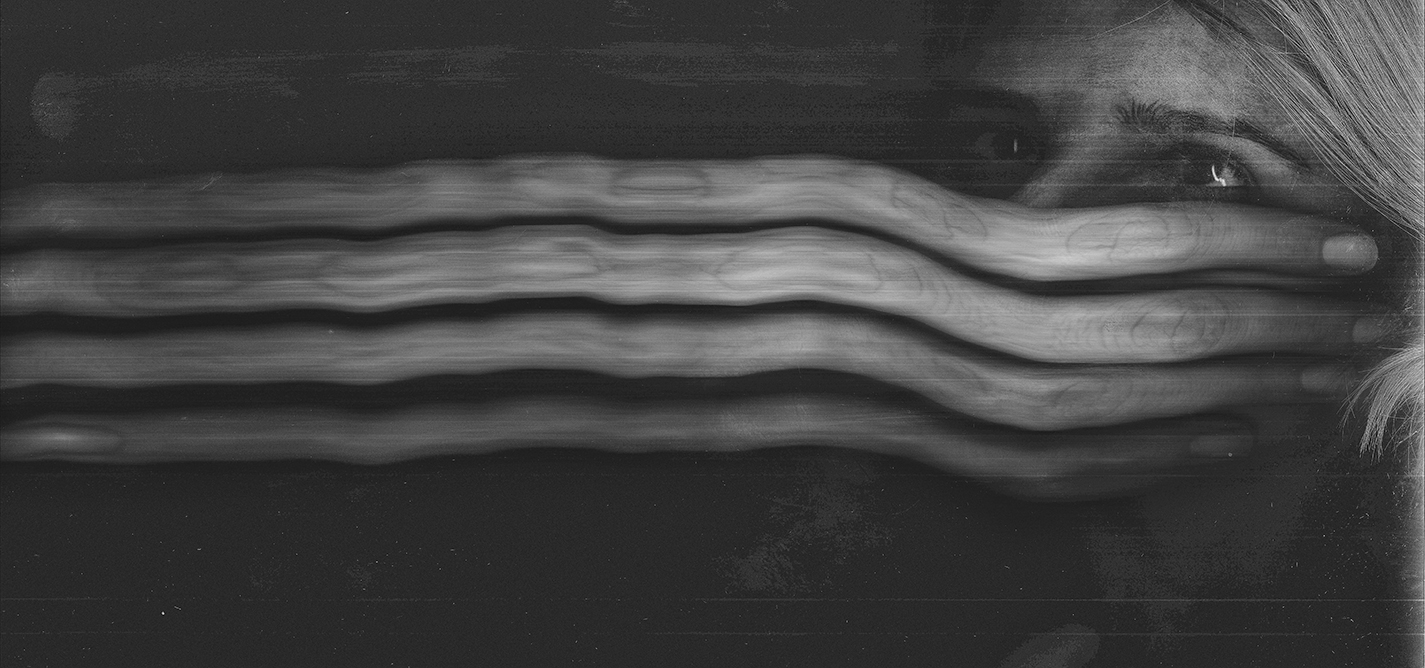

The ‘eternal victims’ of domestic violence

Picking up the pieces of recurrent abuse.

“Every day I insist on leaving the shelter, but even if I go out, I have no place to go."

MeritaDomestic violence — in numbers

NGOs such as KWN estimate that the state’s failure is due to a lack of will to allocate funds, as well as a lack of awareness for dealing with these cases more seriously.

“We need to raise awareness, we need to train service providers — police, medical staff, prosecutors, judges, social workers.”

Tijana Simic

Dardane Neziri

Dardane Neziri holds a Bachelor degree in Journalism and Albanian Language from the Faculty of Philology, University of Prishtina. She is currently pursuing a Masters degree in the Albanian Language. She has been working as a journalist in the daily press in Kosovo for 11 years now. She has been working for the “Koha Ditore” newspaper for approximately six years. She covers mainly politics, justice, education as well as social issues. She is the winner of the prize on the best media story in the field of protection and promotion of children’s rights awarded by the Coalition of NGOs for Child Protection (KOMF).

This story was originally written in Albanian.