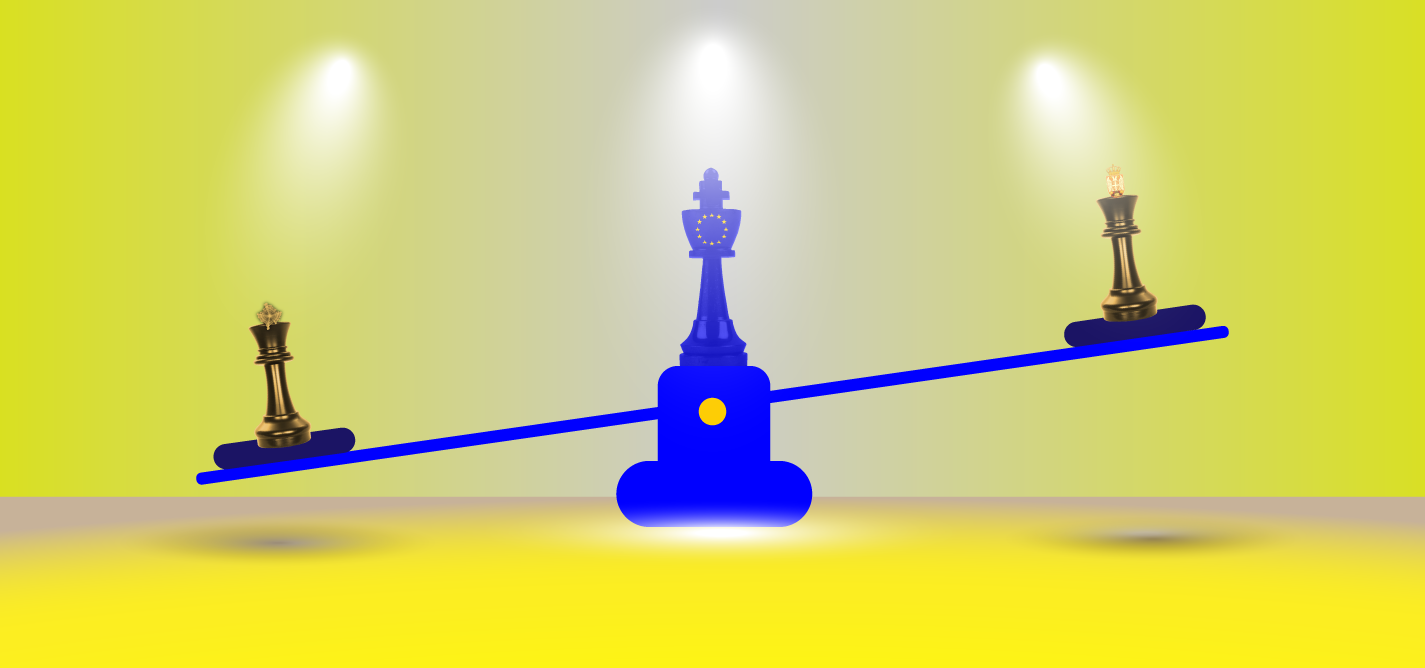

The EU must act to restore trust in its ability to mediate a Kosovo-Serbia agreement

European influence has gone backwards during Mogherini’s tenure.

The current lack of leadership and unity sends the signal that the EU is weak in the Balkans compared to the U.S. and Russia.

It is time for the EU to be straight with Serbia and Kosovo about the future.

Jeton Zulfaj

Jeton Zulfaj is a graduate from Lund University in Sweden, with a masters in European Affairs. He is currently a member of the political party Vetëvendosje!.

DISCLAIMERThe views of the writer do not necessarily reflect the views of Kosovo 2.0.

This story was originally written in English.