A few weeks before the outbreak of the COVID-19 pandemic, a public discussion emerged on whether Sunday should be legally off for workers in the private sector in Kosovo. At that time, I thought it was important to contribute to this discussion from a labor economic perspective.

However, with the situation changing so fast as the pandemic unfolds, it’s important to note that this writing may be relevant only in the long run, after recovering from the unprecedented economic crisis we are about to face.

Having said that, the issue of having Sunday off is nothing but an inquiry on the quest to determine what a normal working week should be. Undoubtedly, the answer won’t be able to evade the arena where the antagonistic interests of the capitalist and the worker lie.

At different times in history, “normal” has been defined differently. But it essentially boiled down to finding the optimal point by moving away from reducing workers to mere labor-power and towards enabling them a dignified life through a well-balanced time between work and leisure.

While it first may seem as a clear-cut discussion in which your stance depends on the side you lean towards, it is a bit more complex than that. What makes it so is the friction of antagonistic interests that takes place in a context where unemployment is the highest in Europe, trade unions are weak and run by incompetent leadership, and the government’s capacities for monitoring and regulating the labor market have been insufficient.

Despite these obstacles, the struggle is far from being doomed to fail. The key is to learn from the paths paved by other countries. History shows that to begin with, workers must organize, and employers should adjust after reconsidering what actually helps — or hurts — output.

How long are working hours currently?

A short discussion with any randomly selected worker in the private sector is very likely to reveal that they work long hours; often without a working contract, health insurance, pension contributions, or paid holidays. While all these issues are interrelated and deserve great scrutiny, the focus here is mainly on the working hours. So, how severe is the situation?

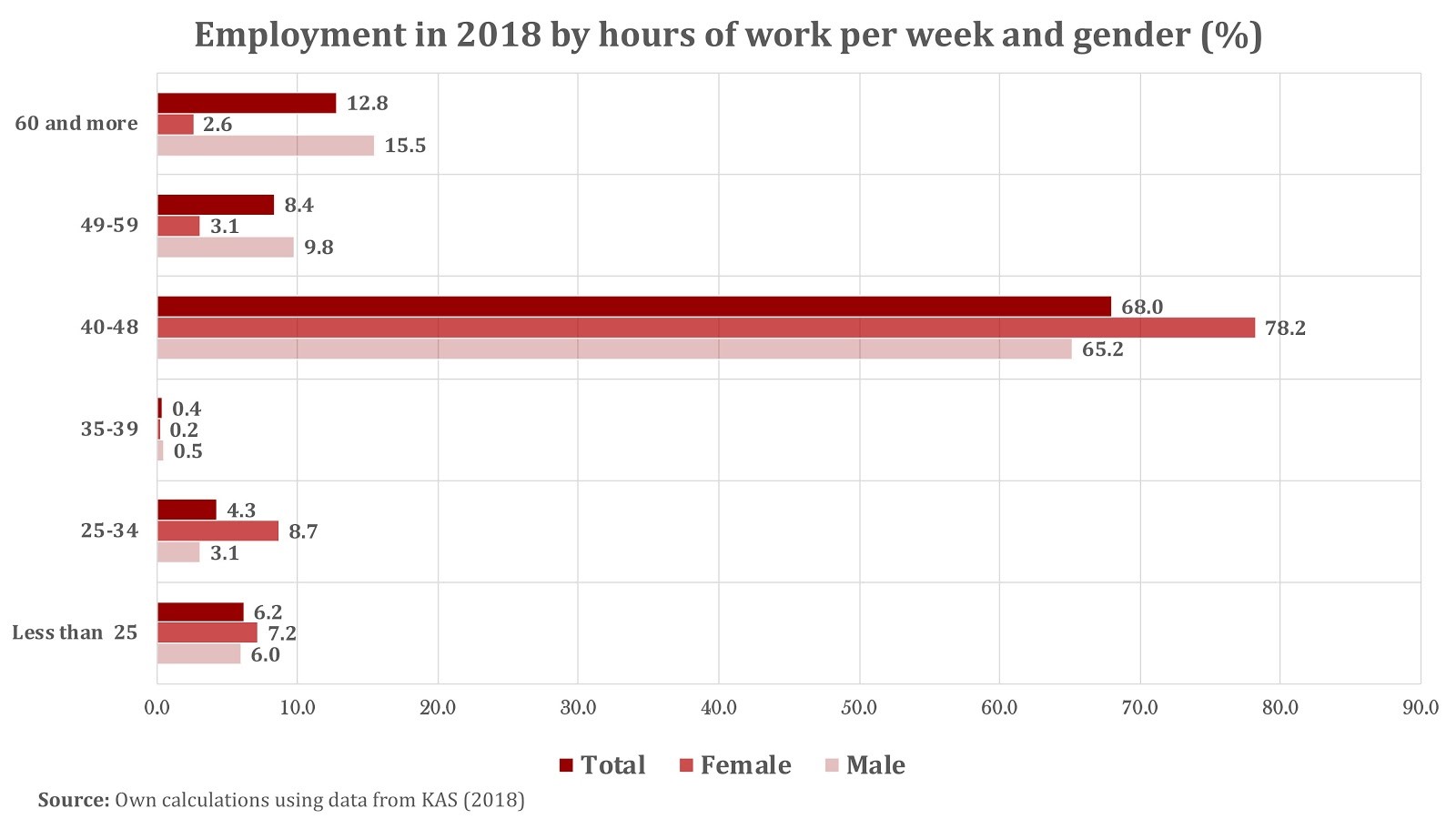

The latest annual Labor Force Survey published by Kosovo’s Agency of Statistics (KAS) for 2018 shows that less than 11% of full-time workers, in both the public and private sector, worked fewer than 40 hours a week, which means that the rest of them — 89% — worked 40 hours or more. Of those working more than 40 hours a week, 68% worked 40-48 hours, 8.4% worked 49-59 hours, and 12.8% worked 60 hours or more.

Overall, in the public sector, both men and women worked an average of 39 hours a week, and in state-owned enterprises men worked an average of 40 hours while women worked an average of 37.

The private sector is a whole different animal — the weekly average hours of work were 48 (49 for men and 44 for women). Due to such stark differences between working hours in the two sectors, it is safe to assume that a great percentage of those working 40+ hours a week are in the private sector.

And when weekdays are not enough, the weekends are used for work rather than for leisure; 70% of workers employed in all sectors said that they sometimes or usually work on Saturdays, and 29.2% of them said that they sometimes or usually work on Sundays. Again, because most (if not all) public institutions are off on the weekends, it is safe to assume that most of those who said that they work on Saturdays or Sundays, or both, are workers in the private sector.

How long do workers in the region work?

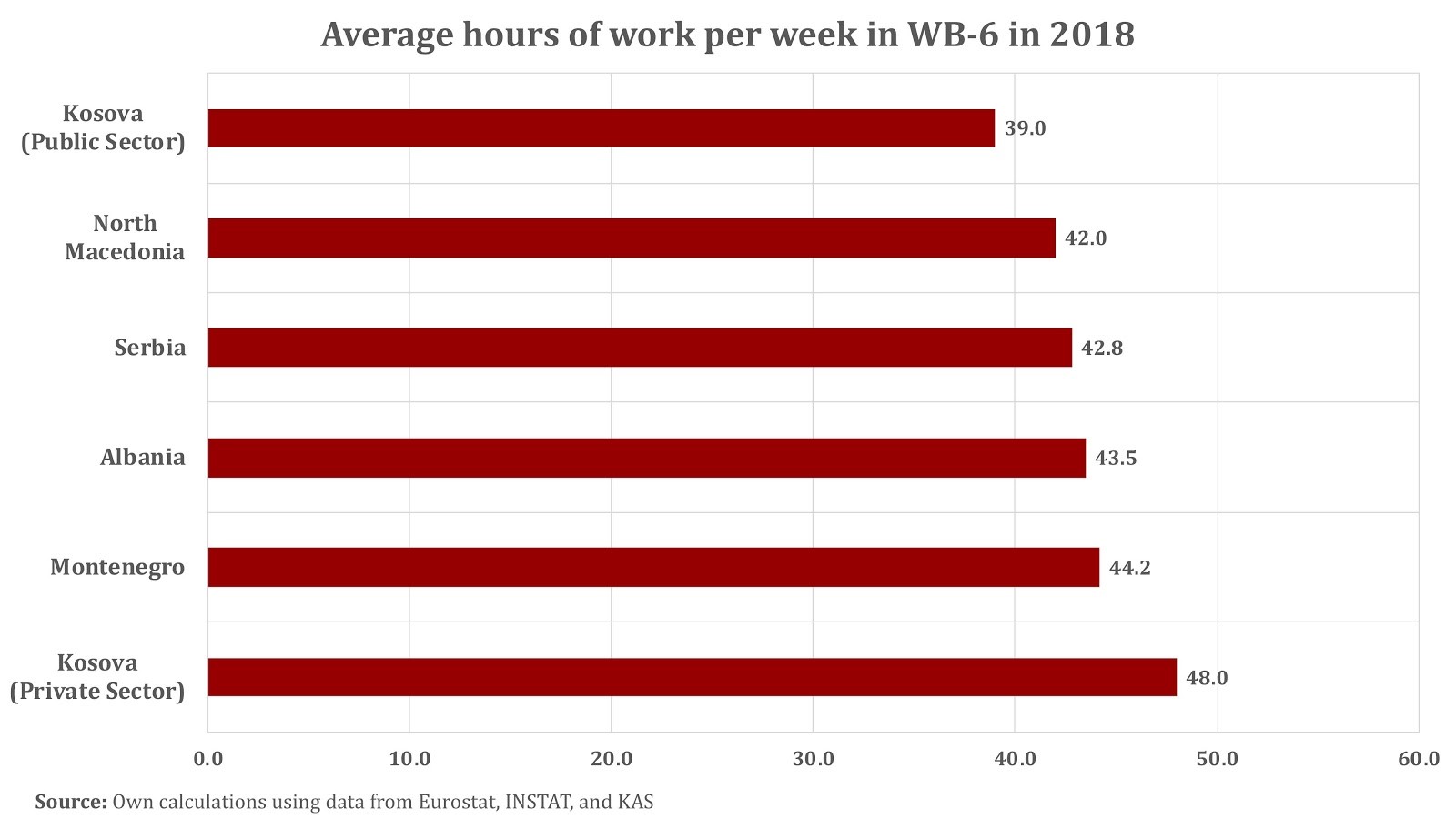

Having seen the length of working weeks in the private and public sector in Kosovo, let’s compare with the region. Even though a direct comparison is not possible since KAS does not provide an overall average of weekly working hours for both sectors, in the graph below we can see a comparison among six Western Balkans countries where Kosovo’s statistics for the two sectors are used separately.

While Kosovo’s public sector is under the weekly average of working hours in all Western Balkans, the private sector is well above it. As a weekly average, Kosovo’s private sector workers work 3.8 hours more than their counterparts in Montenegro, 4.5 hours more than in Albania, 5.2 hours more than in Serbia, and 6 hours more than in North Macedonia.

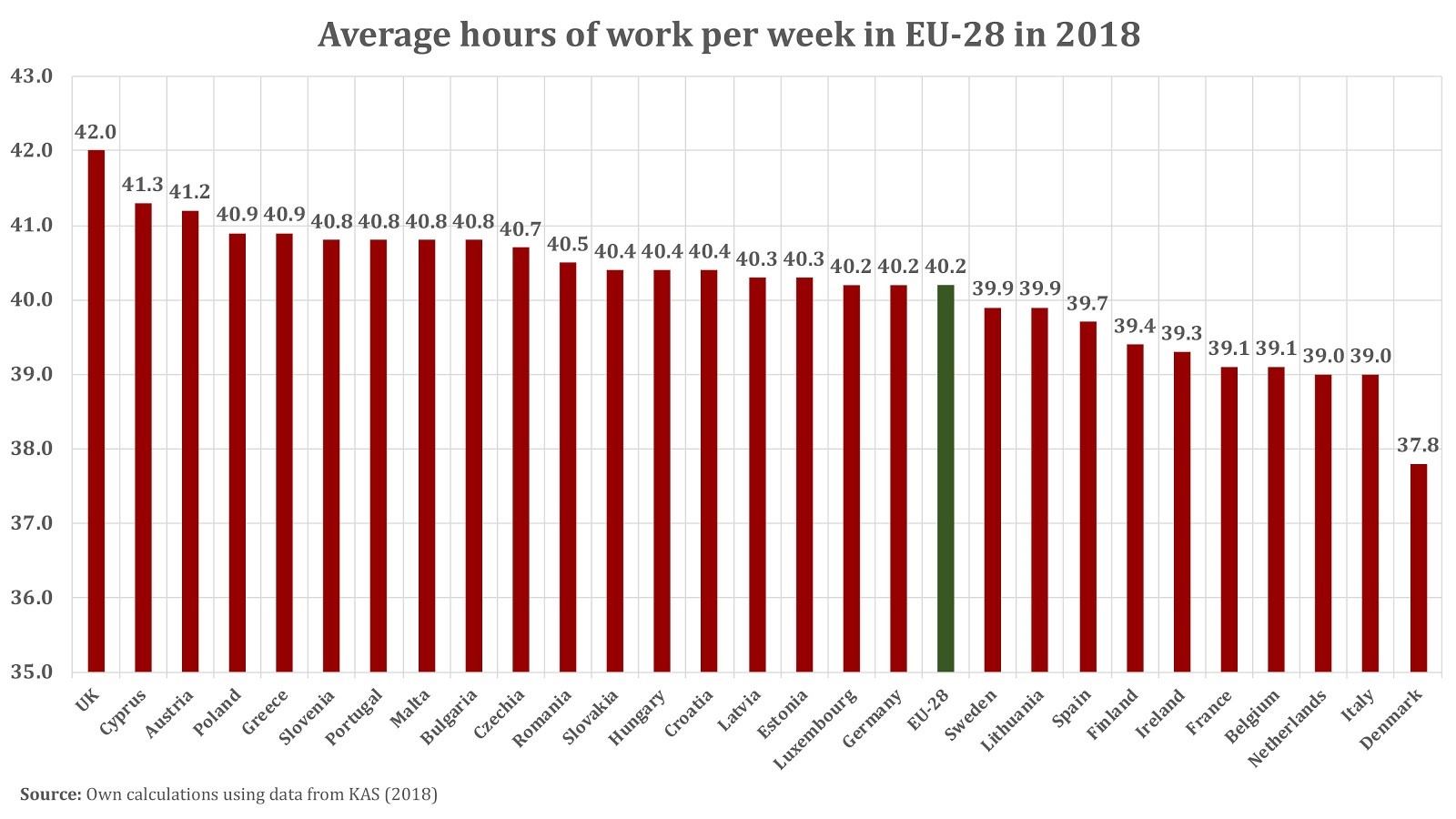

Zooming the comparison further out, we see that the situation of Kosovo’s workers in the private sector does not look better when compared to workers in the EU member states either. The graph below shows the average hours of work per week in 2018 for EU-28 countries, with the United Kingdom included.

In 2018, the weekly average of working hours in the EU was 40.2 — Denmark had the shortest hours with an average of 37.8 and the UK had the longest with an average of 42. This means that each week, Kosovo’s private sector workers, on average, work 6 hours more than workers in the UK, 7.8 hours more than the average of the EU, and 10.2 hours more than workers in Denmark.

It’s important to note again that these are not direct comparisons, in view of the fact that the averages for other countries display both the public and private sector in one place. Regardless, they serve as proxies that provide an approximate comparison of the length of the working week in the region.

That said, the issue is not simply that workers in the private sector are working much longer hours than those in the public sector in Kosovo, and longer than workers in WB-6 and EU-28 countries, because the Law on Labor permits it in certain circumstances. The issue is that more often than not workers are not compensated for working long hours — whether it’s because they lack work contracts or, even when they do, those contracts are not adhered to by employers.

What works against a normal working week?

The first factor that works against a 40-hour working week in Kosovo is unemployment.

For various reasons, including a mismatch between the education system and the economy, the labor supply exceeds the labor demand — as a result Kosovo continues to have the highest rates of unemployment in Europe. In such a highly competitive market, those who work feel threatened by how easily they can be replaced, and any attempt on their part to demand better working conditions is faced by the evident threat that employers can fire them at will.

What allows for this ease of replaceability to be pervasive is the share of employment by the private sector and the general perception of the skill sets needed. In 2018, the top four sectors employing people were the wholesale and retail trade sector with 17%, the construction sector with 11.9%, the education sector with 10.3% and manufacturing with 10.3%.