“Haven’t you seen how they kill women in that country?” says Fatbardha, while peeling potatoes. Crossing the English Channel in a small boat was challenging for Fatbardha — whose name has been changed to preserve anonymity — and her young son and daughter. Nonetheless, she says that she would not hesitate to take the risky journey from Albania again.

Fatbardha left Albania after years of enduring economic hardship and domestic violence. I met her in a youth center in East London, along with other Albanian women and families seeking asylum in the U.K.. They were participating in cooking-as-therapy activities organized by local charities to help female asylum-seekers cope with the anxious wait for a decision on whether they will be granted refugee status.

Albanian women seeking sanctuary in the U.K. have diverse and complex histories. Many of them fear domestic violence, usually from their fathers and/or husbands. According to immigration lawyers assisting Albanian cases, the domestic violence risk is sometimes combined with other risk factors such as blood feuds or trafficking in asylum applications.

“When I say to my clients and ask them, ‘Did you go to the police?’, they kind of laugh at me and say, ‘What do you want me … to be killed?!’ In their village, if you go to the police, reporting against your husband is considered such a big taboo… you would face further violence, not just from father, husband, but others,” said Esme Madill, specialist solicitor at the Migrant and Refugee Children’s Legal Unit (MiCLU), during an online seminar on Albanian asylum claims based on fear of domestic violence.

According to various reports, judicial corruption remains endemic in Albania and because of it, some perpetrators of gendered violence are being let off with lenient sentences. This violence is exacerbated for poor and low-paid women living in close-knit communities in rural areas, where fathers and male partners happen to be friends with the local police. Even when the woman gathers the strength to report the case, the police will often minimize it as a family matter, leaving women without sufficient protection.

“Some women seeking protection are from the village where there is only one school and one doctor. Suppose that woman goes to the police station … before she makes her way back home, the police will have already informed the family, husband and other relatives,” said Flutra Shega, a co-founder of Shpresa Programme, one of the few charities working with Albanian-speaking migrants and refugees in London.

In a recent study exploring how grassroots feminists address gendered violence in Albania and Kosovo, various activists pointed to the Albanian state’s consistent failure to protect women and girls from violence. “But even when you find the strength, you collide with police officers who tell you:… it’s YOUR father that beat you, your brother, your husband. And it’s not the end of the world, so go back home, take it easy, and go on with your life,” said one of the study participants.

The testimonials gathered in the study illustrate a collective sense of navigating patriarchy felt by women and girls from different walks of life. With alarming femicide rates and desperate women resorting to asylum-seeking, why is the Albanian state failing women?

The safety of women in Albania cannot be donor-driven

It is the state’s duty to prioritize prevention of gender-based violence and prosecute its perpetrators. It is failing in this duty.

The Center for Human Rights in Democracy (QDNJD), a Tirana-based non-governmental organization focused on women’s rights, conducted an empirical study on applications for protection orders submitted to the Tirana Judicial District court. The report is part of the monitoring of the justice system towards gender-based violence; its findings paint a bleak picture of weak enforcement of protection orders, lack of safety net and police inaction, which entrap women into abusive situations.

Domestic violence protection orders are civil orders that the victim can get from family court. Either the victim or the police can apply for a protection order. Domestic violence protection orders are a two-stage process. In the first stage, the urgent/emergency protection order is issued. The second stage gives the offender the right to be heard and oppose the order. Based on the trial’s outcomes, the final protection order is issued.

In QDNJD’s collection of statistics from 2000 to 2021, 1,920 lawsuits were submitted to the Tirana court to request protection orders. Only 53% of the cases were accepted or at least partially accepted, while 47% were either refused or paused. In 90% of cases, the abuser is a man and women remain disproportionately subjected to domestic violence.

The QDNJD has identified contradictory measures undertaken by the justice system regarding protection orders. In 28 decisions, the court issued protection orders for both the perpetrator and the victim. In some cases, the court even introduced measures that contradict the legislation against domestic violence, such as the payment of the rent for the abuser by the victim.

Although the police can apply for a protection order on behalf of the victim, they did not do this in a single case. In the bulk of cases monitored by the QDNJD, the victims reported the abuser to the nearest police station and the latter started the procedure by completing the lawsuit request to issue protection orders.

One of the main challenges for the justice system in addressing violence against women is eradicating the culture of impunity that discourages many women from reporting violence. The center found cases of judges using derogatory and misogynistic language against the victims: “Be brief because I don’t want to hear details. I have five other protection orders to deal with after you,” said one judge during a session. In one of the monitored cases, the judge insulted the victim, telling her that “It is you who entered into relationships with married men, and now you come here and ask for protection orders.”

Regardless of The Law on Guaranteed State Assistance, which stipulates the state’s obligation to provide legal assistance, it appears that in only 41% of cases, the victim is assisted by a lawyer. NGOs cover legal representation in most cases, while private lawyers assist 38% of victims. This finding shows the state’s failure to allocate an adequate budget to help victims of domestic violence with legal aid.

State negligence and sham marriages

Years of state underfunding have resulted in limited infrastructures of social care and critical women’s services in Albania. This has forced NGOs to try to fill the gaps, leaving the majority of prevention activities against human trafficking dependent on donors.

Services for mobile victim identification units (MIU) remain crucial to identifying and supporting potential victims of human trafficking. The majority of identifications come from the mobile units rather than from the police or health institutions, which makes these units essential structures. According to Anxhela Bruci, an anti-trafficking campaigner, funding the entire operation of these mobile units and increasing the number of units, especially in under-reported areas, should be a priority for the government’s anti-trafficking national response.

Lack of adequate welfare support and economic opportunities push poor women from marginalized communities into the hands of criminal underground activity. A recent report by the Tirana Legal Aid Society (TLAS) shines a light on the growing phenomenon of sham marriages.

A sham marriage is a marriage of convenience entered into without the intent of creating a real martial relationship. It is usually done for the purpose of one or both of the parties gaining an advantage from the marriage.

Roma women are most impacted by sham marriages. A typical pattern in these marriages is the unusual move of men taking the woman’s surname after the marriage.

Based on testimonials gathered by TLAS, women are offered financial compensation in exchange for entering marriages with men interested in legally obtaining the surname of their female partners. This arrangement may be pursued for various reasons, including obtaining a residence permit, citizenship and escaping legal prosecution.

Rudina Brari, a lawyer at TLAS, noted that “Fake marriages were a practice during communism used by some individuals who needed to get a residence permit to move to Tirana.” Brari added that nowadays, the most common driver for these marriages is regaining mobility after being deported back to Albania from western Europe. “The moment these men get their last name changed, they apply for a new passport and leave Albania as soon as possible,” argued Brari. In one case of fake marriage, a woman beggar was taken from the street to the Civil Status Service to enter into this marriage, said Brari.

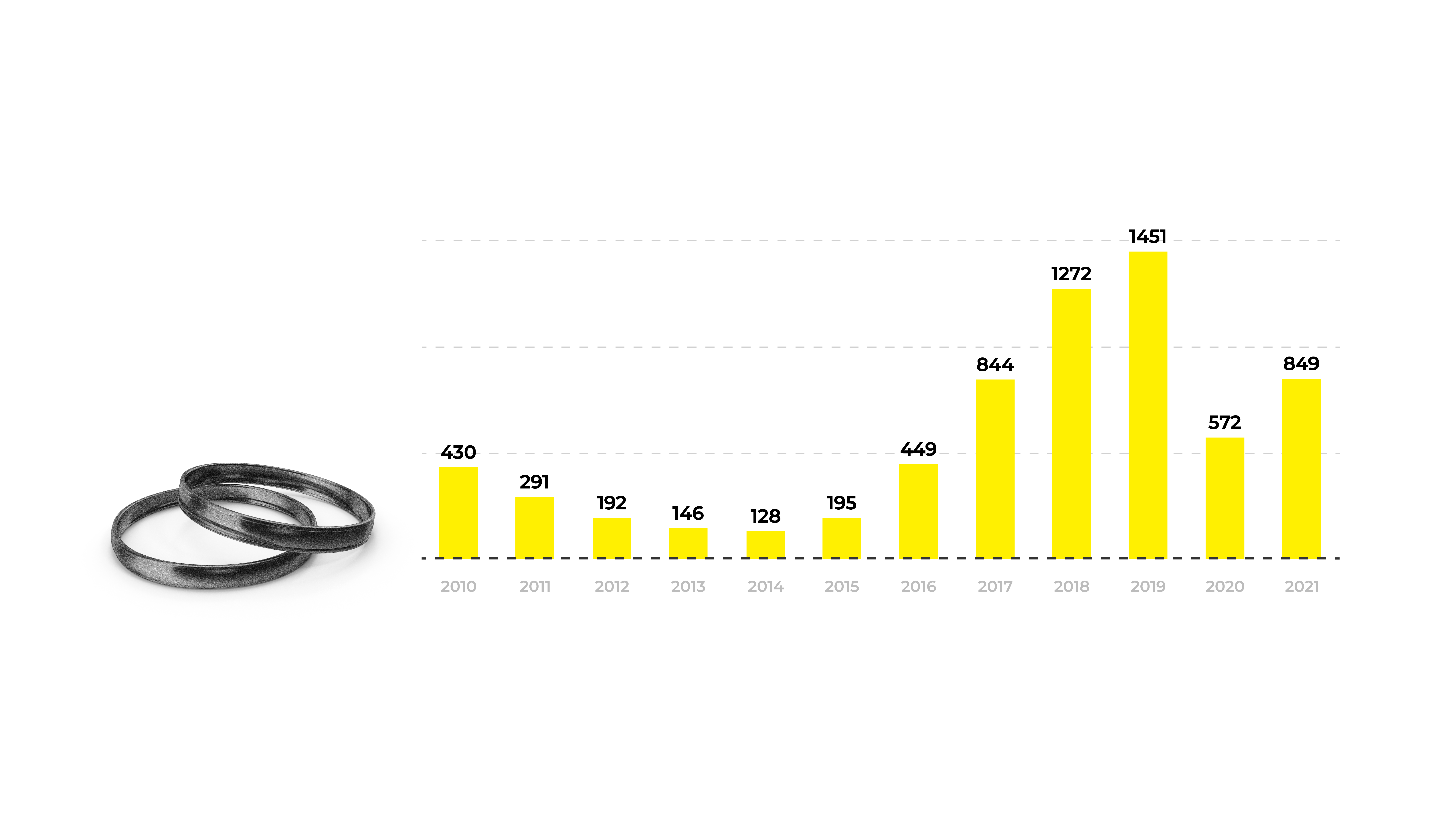

Based on 2013 amendments to a law originally passed in 2009, individuals who have been deported or removed from any other country are ineligible to change their surname. However, the legislation did not anticipate that such individuals would use the marriage process to pursue such name changes. Subsequently, sham marriages allow men who have been deported back to Albania and are interested in obtaining their partner’s surnames to be issued new documents, as shown in the graph below.