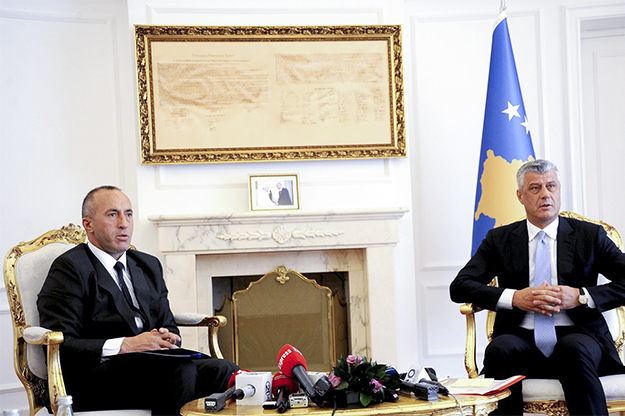

They led the same guerrilla army, but it was always perceived that they were never in awe of each other. Now that they lead the country’s institutions, the relationship between the two main political leaders that emerged from the Kosovo Liberation Army (KLA), Hashim Thaçi and Ramush Haradinaj — the former Political Director of the KLA and the former Commander of the Dukagjini Operative Zone respectively — still seems tempestuous.

Clashes between the two have been frequent in the past two decades. In a book published in 1999, “The Narrative for War and Freedom,” which took the form of an interview with the late journalist, Bardh Hamzaj, Ramush Haradinaj stated that “I respect [Thaçi] as a KLA leader and soldier, but I am not happy with his work in his political activities; I have some objections regarding his ability to unify [the Kosovo political scene] and I don’t like his current stances.” He also criticized Thaçi’s friends in the KLA’s general staff and later in the Democratic Party of Kosovo (PDK), Azem Syla and Xhavit Haliti, saying that “they think that everything in Kosovo has to go based on their judgment.”

Relations were strained further in 2001 with the creation of the Alliance for the Future of Kosovo (AAK), in an era when many KLA sympathizers thought that joining PDK was de rigueur. AAK was led by Haradinaj, until then Major General and Deputy Commander of the Kosovo Protection Corps (KPC), and was the second party emerging from the KLA war, following PDK, headed by Hashim Thaçi.

This step, in the eyes of PDK militants, was seen as a distraction to the cohesion of what was known as the “war wing,” which was facing the “wing of peace,” embodied by Ibrahim Rugova’s Democratic League of Kosovo (LDK). Many of the war wing’s militants accused LDK of hesitating at key historical moments, including refusing to launch an armed struggle after Kosovo failed to benefit from the Dayton Agreement in 1995. Many of them even accused Rugova of treason for his meeting with Milošević at the height of the Kosovo War.

Thaçi was one of signatories that brought about the Kosovo Protection Corps, in which Haradinaj served as a deputy commander. However, Haradinaj’s retirement and subsequent founding of a new political party caused consternation among Thaçi’s supporters. Photo: Creative Commons.

PDK militants saw the creation of a new party emerging from the cadres of the KLA and the KPC — as well as by the agglomeration of parties deriving from the illegal organizations of the 1980s — as a dilution of the war wing. Haradinaj, meanwhile, was considered a puppet who was in cahoots with ‘the enemies’ to enfeeble the war wing.

In 2002, with the formation of a broad coalition government involving all parliamentary parties, the tension between Haradinaj and Thaçi cooled off. However, after the 2004 elections came the climax of the clash between two leaders, the two parties and, ergo, both sides’ militants.

In the aftermath of the election, Ramush Haradinaj agreed to enter a coalition government only with Rugova’s LDK, leaving Thaçi’s PDK in opposition. The accusations that Haradinaj had ‘betrayed the KLA’ were resuscitated, with even senior officials in AAK, including party secretary, Rexhep Selimi — a former KLA General Staff member and current Vetëvendosje MP — resigning from the party.

Dissent peaked in March 2005 during the celebrations for the 6th anniversary of the Prekaz Epopee — the anniversary of the massacre of Adem Jashari and his family; Eid and Christmas combined for the war wing. As the then prime minister of Kosovo and head of this notorious coalition, Ramush Haradinaj, delivered his panegyric, many people from the crowd began to whistle.

Haradinaj, who is known for his direct and extravagant demeanor of communication with the public, neither ignored the obnoxious crowd nor did he act like he heard nothing: “Shut up, you Bllaca commanders. F*** you!,” he shouted. Bllaca was a refugee camp housing the Albanian civil population at the Kosovo-Macedonia border, and with this statement Haradinaj wanted to remind his critics from the war wing who fought and who fled to the refugee camps.

With Haradinaj’s arrest by the ICTY in March 2005 and his trial in The Hague that lasted until 2013, the intensity of the clash between the two ‘KLA parties’ diminished. PDK militants’ frustration reduced over the end of the last decade, especially with the victory of PDK in the 2007 elections that took Hashim Thaçi to power as prime minister, and Kosovo’s declaration of independence in 2008 with the statement being read by Thaçi himself. They seemingly began to believe that, at last, “the right side had won.”

Hashim Thaçi once welcome Ramush Haradinaj back to Kosovo with a red carpet, but their relationship has hit a number of roadblocks since. Photo: Office of the Prime Minister of Kosovo.

When Haradinaj was acquitted for a second time by The Hague tribunal in November 2012, Prime Minister Thaçi welcomed him with a red carpet at Prishtina Airport. Soon after, despite his party being in opposition, Haradinaj began praising Thaçi’s Government. This led many analysts to assess that Thaçi falsely promised Haradinaj that he would take him into the coalition, and give him the Prime Minister’s armchair.

When one was in power and the other in opposition

In the years that followed, Haradinaj’s strong opposition to Thaçi and PDK began. After the 2014 elections, he was among the most active leaders in the creation of the “LVAN bloc” (made up of LDK, Vetëvendosje, AAK and Nisma), which insisted that no one would agree to enter into a coalition with the most voted for party in the elections, PDK, and that they would instead form the government with Haradinaj as prime minister.

Haradinaj claimed that Thaçi again offered him the post of Prime Minister at this time, but he didn’t accept it. Nevertheless, in December LDK “broke the faith” and joined PDK in a coalition government, with its leader, Isa Mustafa, elected as prime minister. In February 2016, LDK would vote for Thaçi’s election as the President of Kosovo in the Assembly.

All that followed for the two years following the formation of the government were protests, protests and protests. Now it was Haradinaj’s turn to accuse PDK and Thaçi of “betraying the values of the war.” In January 2015, the remainder of LVAN, minus LDK and now known as VAN (Vetëvendosje, AAK, Nisma) launched protests against the PDK-LDK government over a statement by an ethnic-Serb minister of Kosovo Government, Aleksandar Jablanović.

The protest did not stop there. After the signing of the Agreement for the Association of Serb-Majority Municipalities and the Agreement for the Demarcation of the Border with Montenegro in the summer of 2015, the VAN bloc’s protests against the government, both in the Assembly and in the streets, began.

In January and February 2016 the protests reached their peak, both by mass as well as by methods, with demonstrations seeing protesters throwing stones and Molotov cocktails, police violence and arrests. In the Assembly, MPs from the three parliamentary parties threw tear gas and were making almost any session of the Assembly impossible to conduct.

Haradinaj was undoubtedly among the most active leaders in this whole confrontation. Aside from throwing tear gas, there were other instances of aggressive behavior from the former KLA commander: from the physical push with the security of Assembly, to insults such as “Kadri Veseli, take these villains and get out of here” or calling the prime minister “Isa the dog.”

Talking about the demarcation of the border with Montenegro, he said about Hashim Thaçi that “this lad from Buroja will not be able to change the Kosovo border.” Buroja, Thaçi’s birthplace, is a village in the Drenica region. All of these actions, consequently, led to the rise of aversion and irritation toward Haradinaj among the ruling parties’ militants, especially those from PDK.

But this state of affairs also didn’t last long. In May 2016, it was clear that VAN was split. Vetëvendosje was out of the bloc due to disagreements with the other two parties, and the year and a half of intensity caused by this unified oppositionism ended.

Haradinaj’s language softened, and in May 2017, on the eve of the start of the election campaign for the early parliamentary elections, Haradinaj’s AAK formalized a coalition with PDK and Nisma, the third party emerging from the KLA (formed after a split in PDK in 2014).

Haradinaj went from one of the biggest critics of Thaçi’s PDK when in opposition to becoming the prime minister of a coalition government including PDK, and being inaugurated by President Thaçi. Photo: Office of the Prime Minister of Kosovo.

It was the first time that all of the former KLA commanders had joined together and entered the coalition. The war wing was united against the peace wing — a coalition between Mustafa’s LDK and Behgjet Pacolli’s AKR. It seemed that the old divisions between the ex-commanders had come to an end.

However, Haradinaj did not make a direct coalition with his old opponent, Thaçi, as he was now president of the country and not PDK leader. However, according to some MPs of the coalition itself, Thaçi was the “godfather” of the ‘PAN’ (PDK-AAK-Nisma) coalition .

Clashes even in coalition

The PAN coalition emerged as the winner of the election with Haradinaj being elected Prime Minister in September 2017. But the fact that he was now an institutional leader, alongside Thaçi, did not mean that their long-standing disputes were over.

Recently, in a perverse situation, it is Haradinaj who has usurped the position of the flag-bearer of resistance to President Thaçi, and his ideas. While opposition parties have spent much of the mandate attacking each other, the parties making up the coalition have been providing the opposition to each other. Kosovo has been ipso facto functioning with two parallel political scenes which do not deal with each other but fight among themselves, government on government, opposition on opposition.

It wasn’t always like this. Haradinaj started his term as Prime Minister with a reception in the Presidency from Thaçi himself. Both were careful not to open sensitive political topics, such as the demarcation agreement with Montenegro that at that time had not yet been passed in the Assembly. They focused on topics they agreed upon, such as achieving visa liberalization from the EU.

Another common point which seemed to unite the two former foes was a distaste for the Kosovo Specialist Chambers and Specialist Prosecutor’s Office, alternatively known as the “Special Court.” The court is charged with trying war crimes committed by the KLA and is based on a report compiled by Dick Marty, which names Thaçi personally. There have also been suggestions that Ramush Haradinaj’s brother, Daut, may also face an indictment.

Despite the potential for his own indictment, Thaçi was a key figure in passing the constitutional changes required to create the court in 2015. However, during a presentation of a report on the public perception of the Special Court in October 2017, President Thaçi changed tack, attacking its validity. “Kosovo kept its promise, it founded the Court,” President Thaçi said. “The international community did not accomplish any of [its] promises. Rather, Kosovo’s Euro-Atlantic journey was hindered.”