Lend Mustafa began to donate blood when he came of age. To the 23-year-old, who works as a project coordinator at CEL Kosovo, it represents a form of civic engagement that he says is very important to him.

He continued to do so regularly until, one day in 2018, he reached the mobile donation unit of the National Blood Transfusion Center of Kosovo (QKKTGJ) on Mother Teresa Boulevard in central Prishtina.

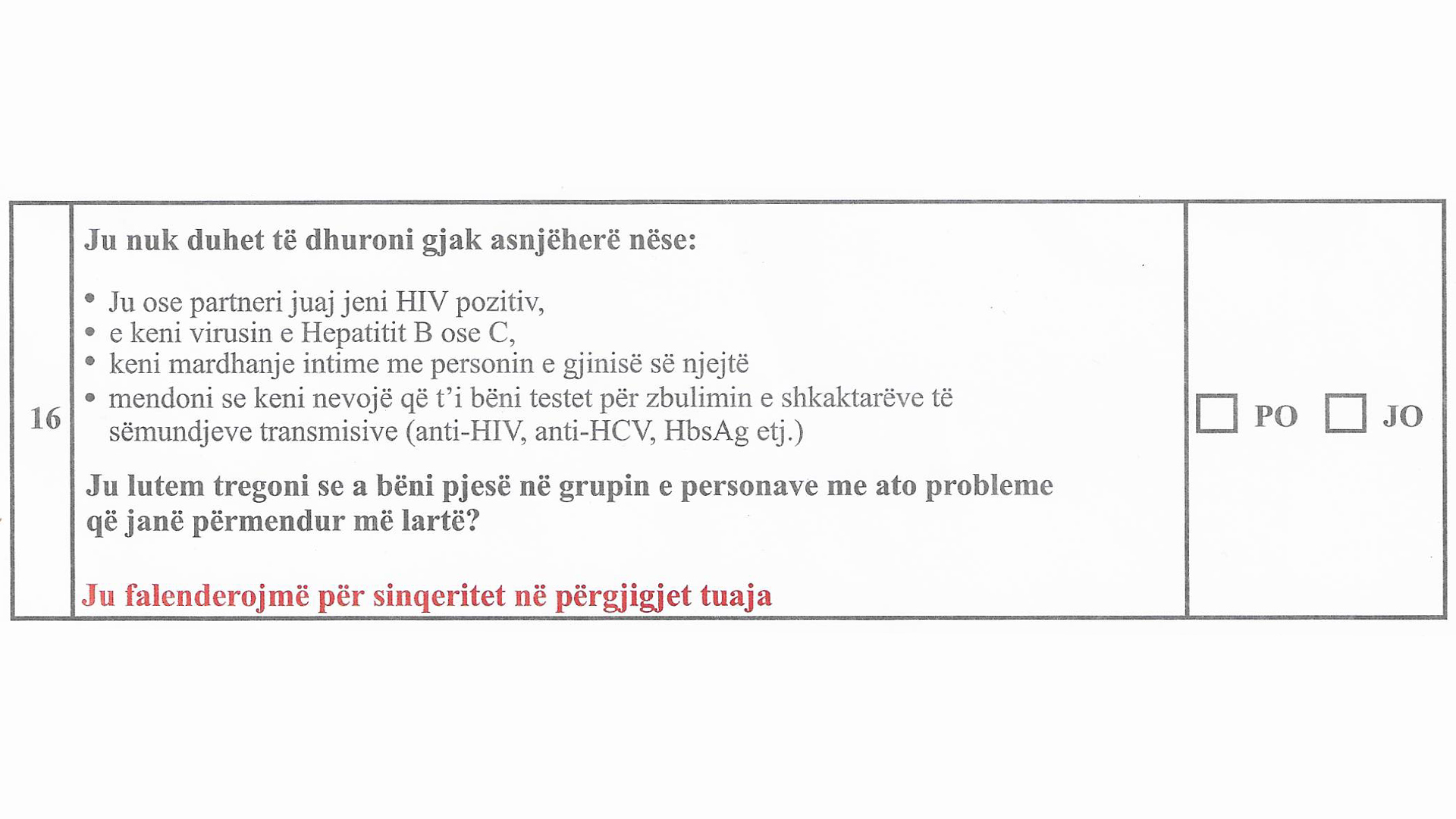

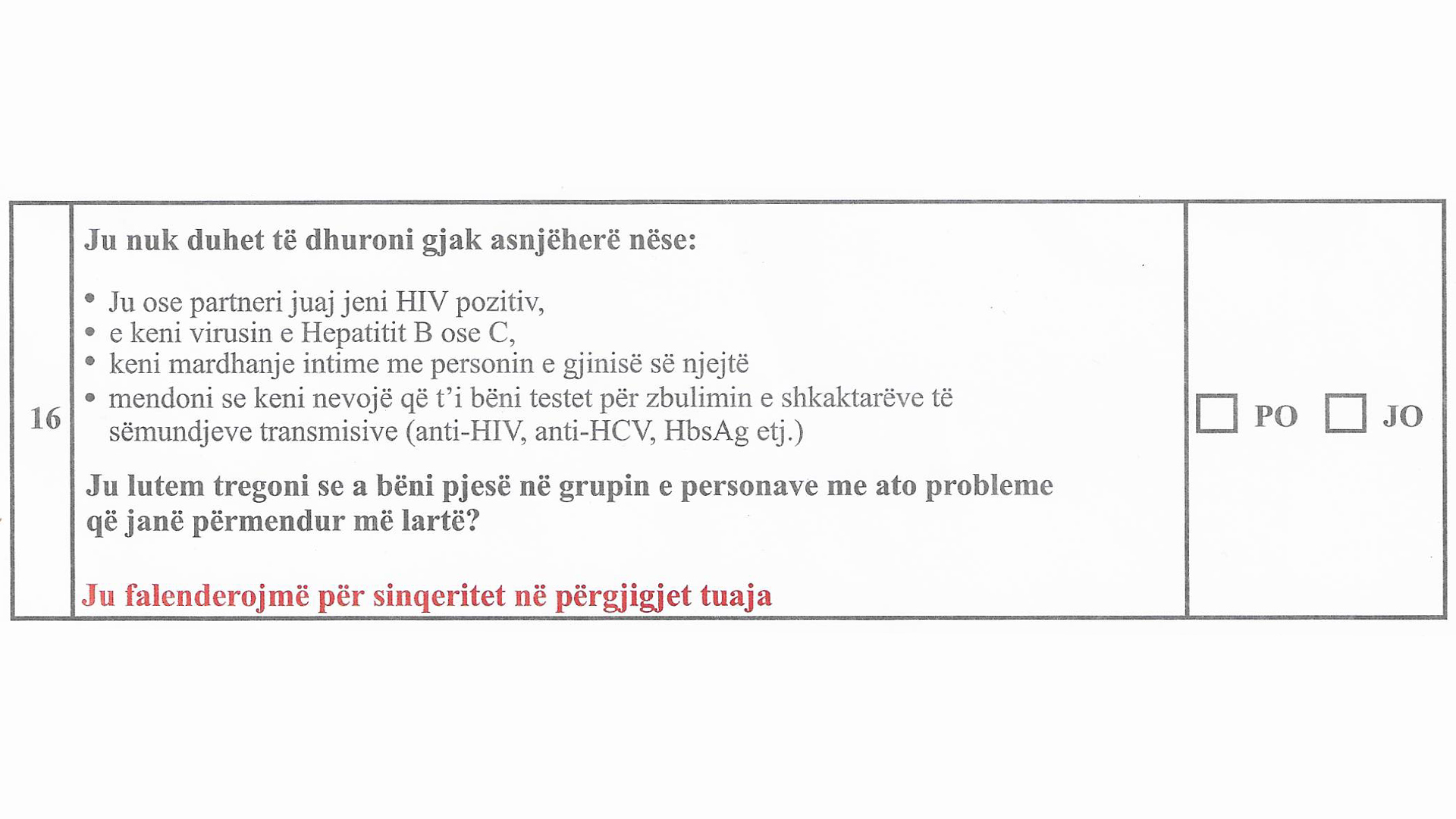

Lend recalls that when he approached them to donate as usual, he was handed a form for the first time that he was asked to read carefully. At the end of the form, he was shocked to find a sentence that read: “You cannot donate blood if you are a person who has had sexual intercourse with someone of the same sex.”

When he questioned the rationale behind that sentence, he says one of the nurses present responded shortly: “Because of HIV.” He was doubly surprised, as another sentence in the same form had already clarified that one could not donate blood if they have HIV or any other STI.

The screening questionnaire currently used by QKKTGJ asks potential donors if they “have an intimate relationship with someone of the same sex.”

Lend says he tried to explain that he regularly gets checked for HIV and has always tested negative but that he was abruptly dismissed with a “We’re not responsible for this form anyway” — and barred from donating.

Describing his conversation with the nurse, Lend recalls that “her approach was not friendly at all; she was just trying to get rid of me and she seemed a bit worried, although I didn’t understand the reason why.”

Official confusion

Blood donation policies are a hotly contested issue that countries throughout the world have been grappling with for years. This is because of concerns around the possibility of infecting patients with blood-borne diseases, particularly HIV — something that occurred some 40 years ago, but has left an indelible mark in the minds of blood collecting authorities and the general public.

The dilemma for policymakers is how to ensure a safe supply of blood — required by hospitals for a number of life-saving procedures — while providing equal opportunities to donate for all those who wish to do so. This is to balance quality and quantity of blood supply — both crucial to patients’ health.

In an attempt to do this, policy makers develop screening policies, but it is not always easy for non-experts to understand the rationale behind a particular policy. That’s why Lend says he asked so many questions to the medical personnel in charge of his screening and why he was disappointed to receive no clear answer, as he believes that “we all have the right to be informed.”

Hoping to get the answers Lend did not receive, we reached out to QKKTGJ to receive clarifications on the pre-donation questionnaire that is being used to screen donors in Kosovo, and the differential treatment reserved for the queer community.

HIV vs. AIDS

HIV (Human Immunodeficiency Virus) is a virus that attacks the immune system. It can be transmitted by contact with infected bodily fluids.

AIDS (Acquired ImmunoDeficiency Syndrome) is a condition, which a person may or may not develop after being infected with HIV.

If treated properly, people with HIV (sometimes known as “seropositive” persons) can live without ever acquiring AIDS.

Proper treatment can also greatly reduce the chances of people with HIV infecting others.

It is with great surprise, however, that we received from the Center a series of inaccurate, misleading and confusing statements.

Firstly, the Center defended its screening policy by referring to “MSM” (Men who have Sex with Men) only. This is not uncommon for blood screening policies globally.

The issue is that Kosovo’s screening questionnaire permanently excludes from donation both men and women who have had homosexual intercourse. There is therefore a discrepancy between what QKKTGJ says is its screening policy, and what is being carried out in practice.

While not impossible, female-to-female sexual transmission of HIV is extremely rare, and no objective risk assessment would justify special policies toward this category of donors. Since this appears to be implicitly recognized by the Center’s response, it should immediately take the quick and simple step of amending its screening questionnaire accordingly.

QKKTGJ also maintains that “all criteria and standards are set in accordance with the laws and the Constitution of Kosovo, and that in no way do they violate the fundamental rights of certain individuals.”

The main law in question is the Law for Blood and Blood Components, which came into force in August 2018 and states that criteria on admission, temporary or permanent prohibition of blood donation are regulated by a bylaw, to be issued within six months from the adoption of the law. However, no such bylaw can be found online to date.

This brings into question the legality not only of the effective ban on any person who has had sex with someone of the same sex, but of the entire blood collection process in Kosovo.

We have petitioned the Ministry of Health for clarifications on the existence of this bylaw, but have received no answer at the time of publication. It is likely that the mismatch between those who QKKTGJ believes it is necessary to bar from donation (MSM), and those who the screening questionnaire actually bars from donation (all queer persons), is a result of this legal uncertainty.

Read the full response from QKKTGJ here.

What falls under ‘high risk’?

The substance of QKKTGJ’s response also provides cause for concern as it appears to demonstrate a misunderstanding of various international laws and policies.

In this regard, QKKTGJ partially justifies its policies by referring to European Commission Directive 2004/33 — a piece of legislation that, as human rights lawyer Rina Kika remarks, “is inapplicable in Kosovo and does not bind Kosovo institutions.”

However, even if it were applicable, it has been misunderstood or misapplied. The Directive states that persons whose sexual behavior put them at high risk of acquiring serious infectious diseases which may be transmitted through blood should be permanently barred from blood donation.

They then affirm that “like most Transfusion Centers in developed countries of the world” QKKTGJ permanently excludes people who fall into various categories, including those who have engaged in prostitution, those who have paid for sex and “men who have had sexual contact with other men (MSM).”

In QKKTGJ’s eyes, each category “represents a population at high risk of presence of infectious agents in their blood, scientifically and statistically documented by the medical community.”

It is firstly inaccurate to say that the majority of developed countries deny MSM blood donation, with most in fact operating a temporary deferral policy that requires a defined period of time to have passed between the last time they had sex and their eligibility to donate blood.

But QKKTGJ’s application of “high risk” is also problematic.

What the Center fails to mention, however, is data that is specific to Kosovo.

The Commission Directive quoted by QKKTGJ operates a risk-based distinction. While individuals deemed to pose a “risk” should be allowed to donate only after a certain period of time, those deemed to be “high risk” individuals should be permanently barred.

When it comes to individuals whose sexual behavior puts them at high risk of blood-borne infectious disease, what the Directive does not specify, is which specific categories of people or sexual behaviors fall under this definition. This responsibility is given to national authorities, to be carried out on the basis of country-specific epidemiological data and risk assessment.

QKKTGJ argues that according to the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA), men who have sex with men continue to represent the population with the highest risk of HIV infection — this, it says, automatically put them in the “high risk” category and justifies their permanent deferral.

What the Center fails to mention, however, is data that is specific to Kosovo. As a matter of fact, UNAIDS data show that “the HIV epidemic [in Kosovo] is the smallest, in terms of registered cases, in the Euro region, and one of the smallest in the world.”

On top of that, the QKKTGJ incorrectly affirms that “the United States and Canada permanently exclude MSM from voluntary blood donation.” However, the FDA has actually recently issued guidelines recommending a temporary, three-month deferral for MSM. Canada adopted the same policy in 2019.

A balancing act — not a competition

In justifying its blanket-ban toward MSM, QKKTGJ contends that it is “applying the primum non nocere (first, do no harm) principle” and that it is “committed to ensuring that patients who receive blood will incur in health benefits only, and no harm or serious illness.”

In other words, it is suggesting that the do no harm principle inevitably means banning men who have sex with men from donating blood.

Understanding this argument is fundamental, as it is normally the key reasoning behind lifetime deferral for MSM.

In 2015, the Court of Justice of the European Union (CJEU) clarified this matter. In the so-called “Léger case,” in which a French man challenged France’s permanent deferral toward gay men, the Court laid out limits to how national authorities, following the abovementioned EU Directive, can adopt restrictions to blood donation.

The Court noted that such restrictions must, as is obvious, aim to maximize safety for blood recipients — our principle of primum non nocere. While doing so, however, it stated that they must also ensure full compliance with the principle of non-discrimination and the principle of proportionality.

In simpler words, limits to blood donation, while necessary, cannot be arbitrary.

Respecting proportionality and non-discrimination can have a positive impact on the right to health.

Compliance with the principle of non-discrimination entails that such limits are based on country-specific and reliable scientific data, so that restrictions to blood donation do not arbitrarily differentiate, or discriminate, potential donors for reasons other than according to scientific evidence.

Compliance with the principle of proportionality entails that these restrictions are as limited as possible: If two potential policies bear similar levels of risk, the one with fewer limitations shall be preferred.

Just like the EU Directive itself, the Court’s decision is not technically applicable in Kosovo law, but it is useful for highlighting that the do no harm principle and the principles of non-discrimination and proportionality are far from mutually exclusive.

In fact, respecting proportionality and non-discrimination can have a positive impact on the right to health.

Let’s use a hypothetical example.

In Kosovo as in many other countries, men are more likely to be HIV-positive. Hypothetically, a blanket-ban of all men from donating blood would therefore statistically ensure lower risks to blood recipients of contracting HIV.

Yet, no blood collection authority has adopted such a ban, as they realize they would unfairly treat different individuals — men who are HIV-positive and men who are not HIV-positive — in the same way. This, in turn, would hinder the right to health of blood recipients, as it would limit an already scarce blood supply.

What applies to all men also applies to men who have sex with men.

Advancements in science — and knowledge

In response to the Léger Case, the then French Minister of Health admitted that “today, no one can deny that this permanent ban is experienced as a presumption of [HIV] seropositivity of gay people.” Aware of this bias, France has since lifted its permanent ban toward donation by men who have sex with men.

The assumption that HIV-positivity is linked to sexual orientation, as opposed to certain sexual practices, is not uncommon. This belief has historic roots, which can be traced back to the first breakout of AIDS — initially known as “Gay Related Immune Deficiency” (GRID).

In the ’70s and ’80s, when we knew little to nothing about HIV and how to fight it, countries introduced different screening policies based on whether donors were homosexual or heterosexual. This happened as a consequence of the “contaminated blood scandals” where thousands of blood recipients were infected with HIV and hepatitis viruses due to contaminated transfusions carried out at that time.

While some countries have kept these policies unvaried, protocols to ensure safe blood collection and technology to detect blood-borne diseases have improved dramatically.

In light of these advancements in science, only a small minority of Western countries continue to permanently bar gay men from donating blood.

The introduction of Nucleic Acid Testing (NAT) for HIV in the late ’90s, for example, has since reduced the “window period” — that’s the period between the moment in which blood gets infected with HIV, and the moment in which a test may actually detect the disease — to as little as seven days from exposure.

What we know of HIV has also progressed remarkably. We now know, for instance, that HIV is not a disease that is peculiar to gay men — globally, women and girls now comprise almost half of new infections. Unfortunately, prejudice against minorities — alongside practices established during those first years of ignorance — has often perdured.

In light of these advancements in science, 40 years later, only a small minority of Western countries continue to permanently bar gay men from donating blood. The majority have recognized that scientific progress has created room for more inclusive screening policies, and have enforced temporary suspensions on blood donations, or no suspension at all.

Positive examples elsewhere

Part of this progress has consisted in moving from differential treatment being reserved for gay men, to differential treatment being reserved to men who have sex with men — including bisexual men and men who do not identify as queer although they have had sexual intercourse with other men.

This new classification correctly shifts the focus from sexual orientation to sexual behavior, and recognizes that being gay is no prerequisite nor automatic predictor of HIV status.

No one denies that the MSM community normally presents a higher incidence of HIV. Nevertheless, the fact that MSM are statistically more likely to have HIV does not necessarily make a blanket ban toward them the most reasonable option on the table.

Contrary to what QKKTGJ asserts, the vast majority of developed countries have found reasonable ways to allow (healthy) MSM to donate, while ensuring that the quality of donated blood is not diluted.

Some, like Canada, the U.S., France, Australia and many others, have adopted a temporary deferral toward men who have sex with men — from three to 12 months, depending on the country.

All these periods of time are many times the window period for NAT tests to detect the presence of HIV. These countries have amended their policies, often in consultation with LGBTIQ organizations; when moving from permanent to temporary deferral, no increased risk for blood recipients has been detected.

Other countries, like Italy and Spain, have adopted a “gender neutral” or “risk-based” approach. Most recently, in late 2020, the UK has also shifted to this policy, after completing a two-year evidence-based review.

The transition to an individual risk assessment system has had no significant impact on the rate of HIV-positive blood.

This approach stems from the self-evident truth that a person does not acquire HIV because he is gay, nor by having sexual intercourse with another man. If a person acquires HIV, it is because they have entered into contact with infected bodily fluids, regardless of whether that person is gay, has had sex with a man, or even whether they are a man themselves.

Following this reasoning, in 2001 Italy — which has a relative estimated MSM HIV-positive population two to three times that of Kosovo — adopted a system that flags all sexual behaviors that can be considered as risky, in all donors.

Consequently, all donors are temporarily barred from donating blood for a four-month period from when they last had sex with a new partner. Individuals who adopt “high risk” behaviors, such as frequent occasional sex, are barred from donation, irrespective of their gender or sexual orientation. In other words, in Italy, the distinction between “high risk” and “risk” categories of sexual behaviors is based not on gender or sexual orientation, but — surprisingly enough — on sexual behavior.

Italy’s higher rate of donated blood that is found to be HIV-positive compared to countries not operating individual risk assessments is sometimes put forward as a reason not to move toward a “risk-based” approach. But Italy already had a higher — albeit negligible — rate of HIV-positive donations.

Studies show that the transition to an individual risk assessment system has had no significant impact on the rate of HIV-positive blood, nor on the ratio of homosexual-to-heterosexual HIV-positive donors. Moreover, due to the various safeguards in place, higher rates of HIV-positive blood at the time of donation do not seem to have translated into a higher number of cases of HIV infections through blood transfusion — according to the head of Italy’s National Blood Center, there has not been a single documented case of infection through blood transfusion in Italy for more than 25 years.

Italy’s example should serve as a reminder that screening policies are just one among many factors to be considered when ensuring the quality of transfused blood — and that they must be based on fact-based research, which might disprove pre-held assumptions.

As Lend admits, “such procedures may be very difficult and I understand that, especially since I have no medical background. I am just wondering how other countries can avoid such discriminatory policies, and we cannot. I believe this is just another issue that is not a priority for our institutions.”

Time to update ‘do no harm’ thinking

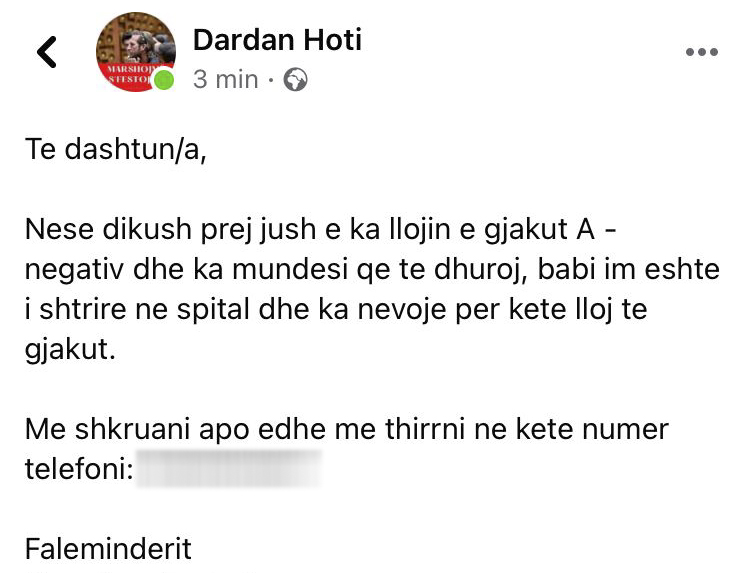

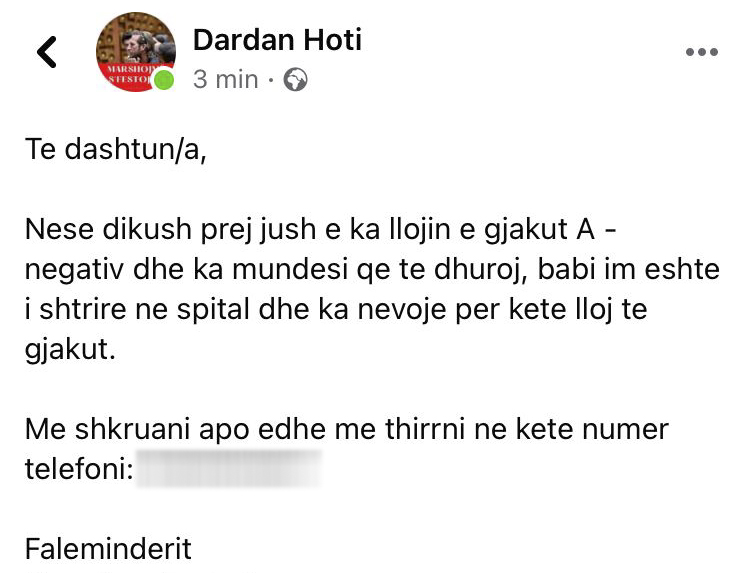

Now, one may argue that, although permanent deferral toward MSM may be considered as excessively cautious, it does not dramatically impact blood supplies. Considering that in Kosovo is not uncommon for people to ask for blood donations on social media when a family member is in need due to severe blood shortage in public hospitals, it does not seem that the state can safely alienate healthy MSM or queer individuals from blood donation.

Requests by individuals for blood donations are a common sight on social media in Kosovo, such as this one by (co-author) Dardan himself.

One may also argue that, as donating blood is not a right, permanently barring MSM from blood donation, however unsubstantiated, does not violate any right of the queer or the MSM community. This seems to be the reasoning of QKKTGJ.

Quoting a Canadian judge adjudicating a similar case to the Léger Case, the Center argues: “Blood donation is a gift. A gift is freely offered, but must also be freely received or freely declined.”

Ironically, QKKTGJ failed to realize that in that very case, the judge also ruled that the Canadian Blood Services had failed to present sufficient evidence to outright justify a lifetime deferral toward MSM — Canada subsequently lifted its permanent ban.

Beside this, while donating blood is surely a gift and not a right, queer people still hold the right not to be subjected to unreasonable disparity of treatment in all fields of public life; this would seem even more applicable in acts of civic engagement, social responsibility and philantropy such as blood donation. This is why, despite his painful experience, Lend still felt the need to check the questionnaire from time to time — “in case they changed it,” he says.

Moreover, QKKTGJ’s current position neglects the social, political, and even health-related consequences of such a policy. In human rights lawyer Kika’s opinion, upholding such a blanket ban would further enhance prejudice against LGBTIQ persons.

“It would also reinforce the prejudice that LGBTIQ persons are sick and carry diseases and especially it would create the space for people in Kosovo to continue thinking that being gay is a disease or an abnormality,” she says. “The latter is particularly important in the context of Kosovo, given that our school books still contain such outdated and mistaken references to sexuality.”

The fact that Kosovo health authorities base public health measures on considerations other than science is particularly concerning.

It is largely believed that misconceptions around sex, sexuality and the epidemiology of HIV actually amplify the propagation of the infection. A recent rise in HIV infections among men who have sex with men in Kosovo has been linked by some to the ongoing stigma around homosexuality, difficulty in accessing healthcare, endemic homotransphobic violence and discrimination in what is believed to be the most homophobic contry in the region.

So the fact that Kosovo health authorities base public health measures on considerations other than science is particularly concerning.

While Kosovo health authorities claim to uphold the principle of “do not harm,” screening policies that are not based on modern science do cause harm. They harm LGBTIQ persons, by perpetuating outdated misconceptions on HIV and the queer community, and they harm patients in need of blood, by unnecessarily limiting blood supply.

As Lend put it: “It felt really bad that they prevent us from doing such a humane act, but it proved my point. When it comes to such procedures, we [authorities in Kosovo] are so unprofessional that we never try to change something or question a form when we receive it from foreign places. We just get whatever is given to us — as long as it does not affect the privileged.”

Feature image: K2.0.