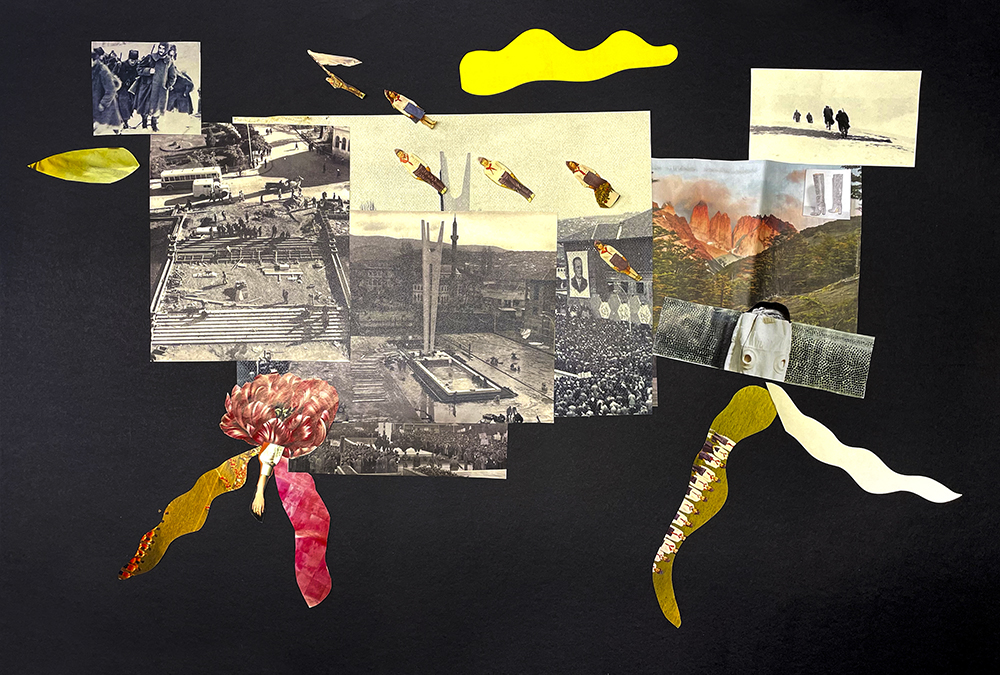

Of statues, grandfathers and stories caught in between.

Walking around Prishtina’s crowded central streets, it’s impossible to avoid coming face-to-face with figures from Kosovo’s past.

In the space of a few hundred meters, Ibrahim Rugova and Zahir Pajaziti stand tall as they look out over the squares bearing their names, the diminutive Mother Teresa surveys a small seating area shaded by trees as she nestles a small child in the folds of her habit, and from atop a horse that appears half his size, Gjergj Kastrioti Skanderbeg commands attention from all those beneath him. A little further away, Bill Clinton waves at the rows of built up traffic attempting to enter or leave the city.

Kosovo’s cities are crowded with statues and memorials, their identities forged rarely by a sense of aspiration but overwhelmingly by nods to the past. Statues and memorials participate in the historical discourse by demarcating the public sphere and telling stories about history. Inviting contemplation of past events, they seek a memory community to celebrate them; intended to highlight moments in Kosovo’s contemporary history, they become a memory infrastructure, organizing our relationship with our personal, cultural and national pasts.

Designed with eternity in mind, statues are often perceived to represent a widely held social consensus or to venerate individuals whose life legacy intersects with collective values. But it would be a mistake to view statues as mere neutral symbols of concord and unanimity.

Nowhere has this been made clearer than a little further down the highway with Nikola Gruevski’s infamous “Skopje 2014” project, whose hundreds of new statues flooding the streets of North Macedonia’s capital came to symbolize the political battle for the country’s future through antiquization. The neoclassical façades and seemingly perennial monuments and statues, moreover served to conceal other heritages, in particular, the Yugoslav past.

It takes a whole societal and political value system to collapse for a statue to be removed from public display.

In Prishtina, I walk past Zahir Pajaziti every day; his grandiose militarized statue in the city center communicates the fact that he was an important figure in the 1999 war. But not much has been done to bring to the forefront the circumstances of his martyrdom in a way that is relatable or memorable. For a statue of such a scale, you suppose that it is designed to activate historical dialogue about civilian resistance and liberation war. Though while I am invited to look, what I see is an armed young man whose life story is weaponized. For the majority, war was an experience out of which they emerged as victims, yet the glory that Zahir’s statue projects is too grand to fit into the story of collective suffering.

Not always do monuments and statues serve to remember history, but rather to memorialize a historical figure or set of beliefs. And they are positioned spatially in such a way that their authority is not to be challenged — it is no coincidence that the statues of Skanderbeg and Rugova overlook the central government and Assembly buildings. They cannot be questioned or taken down.

It takes a whole societal and political value system to collapse for a statue to be removed from public display. Deeply revered, Enver Hoxha’s statues were toppled in 1991 only after the fall of the Berlin Wall, and it marked the end of the dictatorship in Albania that he had previously led for over four decades.

When a statue is taken down, it is usually accompanied from some quarters by claims of an attack on history — an attempt to erase uncomfortable truths. During the wave of Black Lives Matters protests in 2020, many statues of slave-traders and owners were torn down in the UK and U.S., sparking a global debate on whether history was under attack. But uncritically equating statues with history discourages other cultures of history and memory communities from giving voice to other narratives of the past, and creates a climate where multiple truths cannot coexist.

Despite the belief that statues are erected to create a cultural memory sensorium, how effective can they really be in telling us stories connected to history? Memorialization and commemoration is still associated with a tangible object and with the tradition of building statues and monuments. In this region, a disproportionate focus on producing statues and memorial sites, at the expense of genuine efforts to produce more — and higher quality — historical research, contributes to a general misconception that telling stories about our communities and remembering our pasts must be done by casting them in bronze.

Depending where I stand in relation to the dominant historical narrative, my gender, ethnicity and family history are either silenced or given visibility.

What statues unquestionably do have the power to do is to affect thoughts and feelings. Erecting and taking down statues both affect how and who we are in public. Depending where I stand in relation to the dominant historical narrative, my gender, ethnicity and family history are either silenced or given visibility. These identity signifiers are negotiated and translated into rights, defining how I participate in public life. What does it mean to live in a city where statues of women are almost absent? Does it mean that women’s experiences will never inform stories about history?

The stories that follow are told with the assistance of multiple narrators. They are about people and memorial sites, and how history comes to them. Open to error, I draw from my own experience and recollections as well as those of others. By bringing together different oral and written sources, I organize them around questions connected to local commemorative practices, nation-building projects, and personal and collective memory.

In this act of turning diverse sources into narratives, I trace the intersection between private and public history. This chorus of voices describing different moments in Kosovo’s contemporary past resists simplification and the linear progression of time, thereby complicating our understanding of history and our reading of commemorative practices.

The Triangle

In February 1944, Minir Dushi was barely 15. As part of the League of Communist Youth of Yugoslavia, SKOJ, he joined the Yugoslav Partisans in Gri, a village in the Gjakova Highlands, as part of the Bajram Curri Battalion led by Fadil Hoxha. But not long after joining, it was rumored that forces from the German army were approaching. Due to a lack of ammunition, the Partisans were ordered to disperse and regroup with other Partisans in other areas. Because Minir was a teen at the time, Commander Hoxha ordered him to go home. He protested, wanting to remain with the Partisans, but Commander Hoxha told him that they were not in a position to effectively wage a battle against the Germans at that time.

Minir’s family had received no news of him in a very long time — he hadn’t consulted them when he had joined the Partisans. After three nights of trudging through the thick snow he arrived home. Concerned that he wouldn’t be safe in Gjakova, the family sent him to work in their textile shop in Kapali Çarshi (the covered bazaar) in Prishtina. At least there, they thought, no one would know of his recent allegiances.

He would stay for two years in Prishtina, living with two different Jewish families. Every Saturday during Shabbat, he ran errands for them, lighting the fire for Mr. Salomon as he read passages from the Torah.

It was far too soon to understand how this local event taking place in the house where he rented a room would be contextualized within world history.

Minir’s friend, Jak, a young Jewish man from the neighborhood who was also their salesperson at the shop, was kind and had a way with people. Jak liked to raise the prices of the textiles so that there was always space for haggling and conversations with the customers. In the end, Jak would sell the goods at their original price. The illusion Jak maintained had the customers emerge from the shop feeling triumphant and as though they were leaving with a bargain.

One late night in May 1944, Minir was at home with the Salomon family and his uncle, who would come to Prishtina from Gjakova each Monday ahead of Tuesday market day. They were about to go to sleep, when they heard a knock at the hammer knocker on their door. It was an unknown military unit.

The soldiers continued to knock hard until they knocked the door down, and in stormed members of the SS “Skanderbeg” division, Albanian units under German control who served only in Kosovo — they had come to take the Jews. Before Minir had time to comprehend what was going on, the soldiers had taken the other members of the household as they were, in their pajamas. Along with around 280 other Jews found in Prishtina, they would be deported to the Bergen-Belsen concentration camp in Germany.

An abysmal silence and emptiness gripped the house, and the horror left Minir and his uncle speechless for days to come. Having been part of the Yugoslav National Liberation Army fighting the war against fascism, he had thought that the SS “Skanderbeg” unit had come to take him. Encapsulated in his own fear, he did not realize that what he had witnessed was part of the Holocaust; it was far too soon to understand how this local event taking place in the house where he rented a room would be contextualized within world history.

Kapali Çarshi was the largest mercantile center in Prishtina. Many craftspeople and merchants had their shops in the Çarshi, offering a rich variety of handmade and imported goods. The shops were crammed in one after the other along the main street, known as the Long Street, which began at the present day National Theater and ran through the plateau that today connects the government building and the Assembly building and ended at Divan Yoli, today’s UÇK Street. Around the Kapali Çarshi there were small oriental-style houses inhabited by the people who owned the shops. The national heritage of the shop owners was mixed, consisting of Serbs, Jews, Turks, Romani and Albanians, all traders in this post-Ottoman town.

In the aftermath of World War II, when the Partisans Minir had once been part of had emerged victorious, the Kapali Çarshi was destroyed by the citizens themselves, who volunteered to undo what belonged to another way of living and prospering in the world. The mercantile lifestyle that had flourished in the Long Street was replaced by new development projects that envisioned a different city center. A center where key institutions were accommodated; governmental buildings, shopping malls, state banks, all of which projected a new state-managed economy and political order.

During the years of post-war transition in this part of the city, local children would go to play on the construction site and would often find beads and trinkets that had previously been sold in shops owned by Jews. But with Jewish life in Prishtina all but wiped out, this obsession was soon discontinued as there were few more relics to be found.

At the heart of the freshly reimagined city center was the Brotherhood and Unity Square. And it was here, on the site where Kapali Çarshi had once stood, that would become home to the Monument to Heroes of the National Liberation Movement that still stands tall to this day.

The Monument to Heroes of the National Liberation Movement was completed in 1961. Bauhaus inspired, the 22-meter tall obelisk with three poles, accompanied by smaller interlaced sculptures portraying the fallen Partisans, was built to commemorate the collective fight during World War II. Designed by the sculptor Miodrag Živković, at the time the monument symbolized solidarity and unity between the three predominant nations living in Kosovo: Albanians, Montenegrins and Serbs. The vibrancy of the wider diversity that had characterized that very spot in the center of the city until just a few years earlier had now been whitewashed in a concrete monument that showed no differentiations.

That obelisk said nothing of the vibrant trading street it had replaced. It was silent on Jak’s entrepreneurialism and Mr. Salomon’s reading of the Torah during Shabat — memories lost with them on the train to Bergen-Belsen.

Instead, it told the story of the revolution and of the brotherhood and unity of the Yugoslav people, the prevailing political consensus of the moment. Commemorating the triumph against fascism by the Partisans and their socialist vision was a means to discipline a plurality of experiences into a single unified narrative. It was also a way of silencing the experience of horror that had taken place at the heart of these communities that now formed part of the Federal People’s Republic of Yugoslavia.

Yet, societies forget that silence too structures narratives around that which is not spoken; leaving a big void in the middle; unwillingly, pointing at that which is absent.

For Skender, and many others like him in Kosovo, his family history was always out of sync with “official” history.

The Monument to Heroes of the National Liberation Movement in Brotherhood and Unity Square was officially unveiled in front of hundreds of onlookers. Skender Boshnjaku, a high school student at the Royal Gymnasium of Peja at the time, recalls being put on a train to Prishtina to take part in the ceremony. Though this was his first time traveling by train, the experience was not as exciting as one might think — it was dehumanizing. The railwagon in which they were placed was destined to transport animals, and he came out of the train feeling like one.

Due to heavy construction on JNA (Yugoslav National Army) Street — the previously named Divan Yoli Street — he remembers it being covered in mud up to the knee. The walk to the newly built square was difficult and undignifying.

But that walk signified their victory — the victory of communism, brotherhood and unity, and Tito. Holding the slogan “Long live Tito,” he listened to the speech delivered by leading Yugoslav communist Svetozar Vukmanović — “Tempo.” According to Skender, Tempo was a sworn anti-Albanian, yet, there he was — an Albanian boy — in support of this grand event. For Skender, and many others like him in Kosovo, his family history was always out of sync with “official” history.

The destruction of the Kapali Çarshi and building of the square and monument in its stead, had been intended to introduce a new beginning for all, one that left behind the debris of the multilayered heritage created by the different communities who lived in Prishtina. However, the official story of brotherhood and unity represented just a fraction of this heritage — that of those who sat well with the grand narrative of the new confederate-in-the-making.

The day ended for Skender in the same way as it had begun; he was sent back to Peja, the way he was brought to Prishtina — as an animal.

Vuk Karadžić

When my sister and I were kids in the early ’90s, we watched Radio Television Serbia 2. Their programming was mostly educational and it was through this that we learned a lot about science, culture and classical music. It was quite boring for us as kids, but not having a satellite meant we had to settle for whatever was on.

Often, they showed documentaries about national heroes and men of letters. This is where we learned about the well-known linguist and reformer of the Serbian language, Vuk Karadžić. Since their programming was relatively poor and repetitive, we became well acquainted with his grandeur.

It was during this time that my sister started drawing Vuk and her knowledge of him began to be conveyed through her sketch pad. For some reason, she sketched him in the nude, complete with areas of the body considered private. Since we were not yet sexually mature — though Freud would disagree — my mother and maternal grandfather, who was visiting at the time, asked my sister about these drawings and in particular about Vuk’s private area. Her response was that this was where Vuk hung his keys.

Statues of historical figures from Serb culture and history started cropping up in the cityscape.

Vuk was not only key to Serbian culture, but by reforming the language, he was said to have unlocked its potential and paved the path toward modern literature. Described in such a manner in the various TV documentary programs, my sister had — reasonably — assumed that he was a man of many keys.

In 1995, a statue of Vuk Karadžić was unveiled in the green area in front of the University of Prishtina’s Philology Department. My sister and I, of course, had an established relationship with Vuk, but most of the Albanian community did not.

Vuk’s sculpted appearance on the university campus was not an isolated event, but part of wider political, social and cultural developments. In 1989, provisions in Yugoslavia’s 1974 Constitution that had secured greater political rights for the provinces had been abolished, and the consequences had been effective immediately. This political shift, which reduced Kosovo’s status from an autonomous province to a Serb-administered territory, affected the public sphere, as all that had previously been perceived as part of a shared history was attacked. Most World War II statues were demolished, and the Museum of the Revolution that narrated the story of the common fight against fascism was closed down. Simultaneously, statues of historical figures from Serb culture and history started cropping up in the cityscape.

Vuk was just one of the guys that my sister and I happened to know. There was also the statue of the poet and philosopher Njegoš, whose figure was a novelty to our cultural sensibilities. His priestly presence was placed on the other wing of the Philology Department. A bit further away, behind the University Library, the structures of the orthodox church were beginning to set in. All of these markers of Serb culture were situated within the university campus.

Changes to the names of streets was another epistemically violent act, disinviting Albanian community identification with the public sphere. As the majority population in Kosovo, Albanians understood this rewriting as an attempt to overturn common values and further alienate them from what had formerly been shared. This defamiliarization with the public sphere deepened as the ’90s wore on.

One of the many enduring legacies of this fracture is that beyond ethnic divide, not much has been done to document the art of the ’70s and ’80s in Kosovo. If historicized, artists’ works are contextualized within nation-based art narratives, entirely disembedded from the Yugoslav ethos. So, it’s difficult to have a clear understanding of Kosovo’s art during the Yugoslav period, or to create larger connections between Serb and Albanian artists, because they are separately studied within their national histories.

When I had the opportunity to conduct my own research on local art history a few years back, I soon came across the Serb sculptor Zoran Karalejić. Despite the cleavages forged over the years, it didn’t take long for me to remember the encounters I had had as a kid with Karalejić’s works. It was Zoran Karalejić who sculpted the statue of Vuk Karadžić that stood for four full years in front of the Philology Department.

Karalejić had been a mentee of the revered Kosovar Albanian sculptor Agim Çavdarbasha. Heavily influenced by his mentor, it was hard to separate the two by simply looking at their works. Karalejić soon became Çavdarbasha’s assistant at the Academy of Fine Arts, and substituted for him in the late ’80s when Çavdarbasha was absent due to illness. Everyone perceived Karalejić as the next Çavdarbasha, because the latter had transmitted so much of his artistic sensibility, and so selflessly, to his mentee. It was therefore no surprise when, in the early ’90s, Karalejić was voted as the new dean of the Academy.

Karalejić’s works were primarily modernist in style. His sculptures, varied in scale and material, were abstract figurations of the socialist tropes.

Vuk’s statue had a different sculptural approach, it was realism. With Milošević in power, Karalejić became part of his ideological apparatus engineering the regime’s self-image. That changed his art practice, but overall the art paradigm, placing the artist at the heart of the nationalist ideology. Vuk’s statue in front of the Philology Department pushed a Serb-centric narrative that the public university’s foundations were rooted in Serbian history and culture.

Throughout the ’90s, that became the reality. After Albanian professors, students and administrators were evicted from the institution in 1991, the University of Prishtina offered a single-language education in Serbian and Albanians no longer set foot in its premises; instead, they organized higher education in private homes in the periphery of the city.

Tied to a truck, Karalejić’s sculpture was dragged throughout the city.

Most certainly, Karalejić was a complex figure — more than history cared to remember. As the newly appointed dean of the Academy of Fine Arts, Karalejić was the one to hand over notice to the Academy’s Albanian art professors that their contracts were being terminated as part of the mass dismissal of Albanian public sector workers for refusing to sign a pledge of loyalty to Serbia; of course, on this occasion he also dismissed his former mentor, Çavdarbasha. And Karalejić took it upon himself to show everyone their place within the newly-established regime.

His statue of Vuk was torn down right after the Kosovo War, during a mass rally on July 2, 1999. Tied to a truck, Karalejić’s sculpture was dragged throughout the city, with eyewitnesses describing the terrible screeching sound left in its wake. The statue was used as a scapegoat of sorts. All the anger that the Albanian community had accumulated during the decade-long oppression was channelled in removing Vuk from his pedestal. Witnesses of the rally also remember a boy hitting hard on the bronze statue with his flip flops, thereby anthropomorphizing the sculpture.

For Albanians, the summer of 1999 was a euphoric episode that represented a transition from oppression to freedom; such a rapid transformation after so many years of trauma and endurance was definitely hard to process. However, beyond the cathartic release of emotion in the moment, tearing down the statue of Vuk did not in itself bring about any lasting closure; quite the contrary — the effects of being denied cultural expression in the Albanian language in the public sphere are still felt to this day.

The League of Prizren

Whenever Muhamed Shukriu was in a bad mood, his wife Margareta would wonder if a roof tile had been misplaced on one of Prizren’s heritage sites. Knowing her husband well, she was well aware that even such a minor event could deeply upset him. Mr. Shukriu was one of the Prizren Municipality’s Department of Cultural Monuments Protection founders in 1967, and for close to two decades would serve as its director.

With the hundredth anniversary of the League of Prizren approaching, in 1972 Mr. Shukriu and his department began designing a memorial complex for it — commemorating the 1878 Albanian Alliance that fought against border changes decided by the Great Powers at the Congress of Berlin. The League also demanded autonomy from the Ottoman Empire.

The new Yugoslav Constitution in 1974, which gave Kosovo increased autonomy and almost the same rights as Yugoslavia’s six republics — including de facto veto power in the Serbian parliament — eased the process of preparing for the anniversary as Kosovo Albanians became free to express ownership over their history and culture without being labeled nationalists.

The site where the residency of the League of Prizren stood had no memorialization infrastructure. It had a plaque, but beyond that looked like any other Ottoman-style house in the town’s center. The site was managed by the state and had been given over to homeless families to live in, so in order to build the memorial complex they first had to find a housing solution for the families. Ten apartments were built in a record time of 25 days. Then they had to build a wall, to ensure that the Lumbardhi River didn’t take over.

There was a lot of work ahead, obstacles were not few, and the 1978 centenary was just around the corner. The memorial complex was to have numerous elements: a thematic library with specialized books studying the League; a gallery of arts with a collection of paintings by the most renowned contemporary artists who had been commissioned to rework this historical event into modern visual language; an in situ museum showing a collection of artifacts connected to the League; and statues of Abdyl Frasheri and Ymer Prizreni — two of the League’s 47 delegates.

All were to be unveiled in a special ceremony. This was a rare opportunity to help recover from the past a history that marked the fight against partition of Albanian-inhabited lands, and it was a historical event that was particular to the Albanian population. So, the memorial complex had to be flawless.

Prizreni’s body had been exhumed and Professor Nemeskéry had conducted anthropological research to gather sufficient information to inform the work.

Come 1978 and the 100th anniversary, Besa Krajku had just gotten her first job at the Prizren Assembly. At the time she was still a law student, but she had nonetheless accepted the role, seeing it as an important opportunity to learn about the affairs of the bureaucratic world. She recalls the hundredth anniversary as a well organized ceremony, and overall an exciting and profound day.

It was the first time she had heard an opera in the Albanian language. The performance, Goca e Kaçanikut (The Maiden of Kaçanik), composed by Rauf Dhomi, had been commissioned especially for the evening’s opening ceremony. Performed by the Radio Television of Prishtina orchestra and Collegium Cantorum choir, it was transmitted live on all Yugoslav television channels.

The statues of Abdyl Frasheri and Ymer Prizreni, sculpted by Agim Çavdarbasha, were unveiled at the memorial complex, followed by speeches from senior Communist Party figure Mehmed Hoxha and leading academic Pajazit Nushi, and songs by the Choir of the Agimi Cultural and Artistic Society.

Since there were no pictures or portraits of Ymer Prizreni, and by then none of his contemporaries were alive to describe his facial features, Çavdarbasha had worked closely with the anthropologist János Nemeskéry to reconstruct former League of Prizren delegate’s face.

With the permission of the Ulcinj District in Montenegro where he was buried, Prizreni’s body had been exhumed and Professor Nemeskéry had conducted anthropological research to gather sufficient information to inform the work.

But during the examination, a further discovery was made: According to the researchers, Ymer Prizreni did not die of old age as had been widely believed, but was murdered in Montenegro where he had sought political asylum. Because the local history of the war against fascism during World War II was told through the paradigm of brotherhood and unity of Serbs, Montenegrins and Albanians, this information was never disclosed to avoid possible animosity among the three nations.

Standing side by side, the life-size statues of Abdyl Frasheri and Ymer Prizreni obeyed modernist principles. Çavdarbasha gave each figure a particular conversational gesture; each holding a paper scroll in their hands — a declaration perhaps. He did not employ heroic iconography, quite the contrary. Placed on a half-meter plinth, he created a horizontal relationship between the founders of the League of Prizren and visitors. There was no mythical grandeur in their representation. Çavdarbasha escaped monumentality and humanized both.

Fastforward two decades to March 27, 1999 — the third day of the NATO bombings. The residency of the League of Prizren was burned down by Serbian military forces; the statues of Abdyl Frasheri and Ymer Prizreni were ripped from their plinths and thrown into the landfill site near Buzagillek. And with that, much of the League of Prizren memorial complex was almost entirely destroyed.

By wiping out the memorial complex, the regime intended to deactivate its power and in doing so render powerless those who identified with the history that the memorial conveyed. But in the context of extreme violence, uprooting the memorial complex merely gave it a new symbolism, turning this site of national pride into a site of national trauma.

After the war, Muhamed Shukriu returned from Albania where he had been deported and forced to seek refuge. He soon found out about the statues’ whereabouts and went to fetch them. But despite returning to work in the Department of Cultural Monuments Protection, he never was able to return the statues of Abdyl Frasheri and Ymer Prizreni to their plinths, and instead they found a new home as sculptures within the League’s gallery.

On the 140th anniversary of the League of Prizren in 2018, new statues of Abdyl Frasheri and Ymer Prizreni, different in style and sensibility to the originals, were unveiled in the center of the League’s memorial complex. They were now also accompanied by another leading figure from the League, military commander Sylejman Vokshi. These latter adjustments represent a subtle intervention in the initial narrative — the reasons for them have yet to be explored.

The paternal grandfather

I never had a photograph with my paternal grandfather. Without it, the traces that can stand in to create a sense of continuity between him and I are so intangible and so few. Our family photographs ended up in the archives of the Yugoslav secret service.

My grandfather, Metush Krasniqi, was a member of the Ilegalja movement. An activist and founder of many illegal political organizations in his lifetime, his political cause was to free all Albanian-inhabited lands and unite them in one country. This most certainly went against Yugoslavia, and for that, the entire family paid dearly.

It was due to who my grandfather was that my sister and I learned early on in life that we could not dress only in red and black. My mother, our sole caretaker, made sure we explored other colors; the entire family was well aware that they could not allow themselves to be careless with symbolic language. They knew all too well that signs continually take on new meanings and that they could quickly get out of hand — the wrong symbolism could mean receiving a visit from UDBA, Yugoslavia’s secret police.

My grandparents’ house also served as a place for my grandfather to meet with other members of the Ilegalja. My grandmother, who had had to raise five children all on her own because grandfather was in and out of prison, could not stand these big-worded political activists; they were the cause of all her misfortunes. In those meetings, as grandmother recalled, there was always one that would collaborate with the secret service and get everyone into trouble.

Like tangible property, intangible heritage, too, is denied to women.

When my mother lived together with her in-laws in a large family unit, their house was raided by the police and secret service every time Kosovo went through a political crisis. During these raids, the secret police confiscated all family photographs. My paternal grandfather would be taken in for interrogation and incarcerated for a few days, months or sometimes years, until the political situation was under control. He was arrested for the first time in 1958 and sentenced to 18 years in prison — the last time he was arrested was in 1985, just months before his death.

I never knew my grandfather. I have only one memory of him, which I don’t think is mine because I was a year and a half old when he died in 1986, aged just 60. My sister and I went to his death-bed to bid him farewell. Due to torture endured in prison, he had a weak heart. The police standing at the door of his hospital room did not let us in. But suddenly, the door flung open and my sister ran between the policeman’s legs and jumped to give him a last embrace.

Trying to come to terms with the obscurity surrounding the figure of your grandfather, you come to understand that to a degree it is also produced by gendered family relations. As a woman you are exposed to family stories but they are not addressed to you. Like tangible property, intangible heritage, too, is denied to women. What I know about my grandfather I’ve learned from my grandmother, mother and paternal aunts, but not from the men of the family.

Stories of him resurface from time to time, in waves, like a trauma, because memories connected to my grandfather are processed by the family with difficulty. People who they had once known no longer acknowledged them in the street, not wanting to affiliate with a family that was not well-regarded by the Yugoslav political system. And written documentation is scant. When grandfather was free, which was a rare event, he wrote little and documented even less. For the members of Ilegalja, expression of care for one another meant leaving no trace behind that could be later used against them by the secret service.

Twenty-five years after his death, in 2011, a life-size statue sculpted by Ismet Jonuzi was unveiled in the Ulpiana neighborhood in Prishtina. Though he still remains unknown to the larger public, the statue alone does not do the work of expanding who he was and what he should represent to our contemporaries.

It fails to provide any detail on his lifelong cause. The paltry, faded lettering never referenced his decades of persecution that were felt

For me, the statue is an opportunity to frame the family photograph I never had.

beyond the individual. No passing visitor would know that, three years prior to his death, this man organized the biggest Ilegalja meeting, with 17 members of the movement present — a large number for a political organization that never gathered in groups larger than three.

Even if such information were added, statues in themselves cannot sustain collective memory.

However, seeing grandfather’s statue out in the open, symbolically offers some form of closure to me and my family, and perhaps, a starting point for discussing the fate of many families persecuted politically in Yugoslavia.

For me, the statue is an opportunity to frame the family photograph I never had. The visual information that photographs carry reveal our lives in snapshots — when our family albums were taken, it became more difficult to retain a sense of our family’s history. Though photographs are not transcripts of reality, as memorial objects they entertain the possibility of returning to something shared and nurtured by all family members.

‘Inflatable Statues’

In a Whileaway Kosovo, a group of young artists and archivists find a text from the 21st century. It’s a retrospective exhibition catalogue from way back in 2015 in which the artist, Sokol Beqiri, mentions an idea of his to an art confidant — a piece to be titled “Inflatable Statues.” However, because the society in which he lived held statues in such high regard, the work was never produced.

The group of artists and archivists take it as a starting point to design inflatable statues, which are replicas of the statues produced between 1961 and 2021 but which have long ceased to be part of the cityscapes of Kosovo.

The statues from this 60-year period are male-centric. They are representations of men in uniform, thinkers and workers; those of women are disproportionately few in comparison. When women are deserving of a statue, they are representations of teachers or religious missionaries. Judging from the archival materials about these statues, the past societies were patriarchichally prudish.

Though these inflatable statues are obscure cultural references, people still like to buy them and in doing so engage in ironic consumerism. They enjoy both form and function. People also take them on their summer vacations and use them as recliners on the beach or to swim with in the sea. With the elements that help us forge understanding having changed dramatically, most of the names of the heroes from this historical period represented through statues are no longer as they were.

Scholars of 21st century epistemology claim that, with few other cultural indicators from that period to go by, people today can’t correctly pronounce — and more often than not misspell — the names of historical figures from that period. With the language having evolved, they say that they altogether fail to understand or connect to that culture.K

Creative direction: Erëmirë Krasniqi & Nita Salihu Hoxha.

Design: Nita Salihu Hoxha.

This story is supported by the Rosa-Luxemburg-Stiftung Gesellschaftsanalyse und politische Bildung e.V. – Office in Bosnia and Herzegovina.

- This story was originally written in English.