Aleksandar Hemon was in Chicago when the Bosnian war began. He immediately became a displaced person, unable to return home to Sarajevo. But he learned how to thrive in America.

In books such as “Nowhere Man,” “The Question of Bruno,” “The Lazarus Project,” and in his latest book “My Parents: An Introduction / This Does Not Belong to You,” the author focuses on displacement, Sarajevo and identity.

He has won some of the most prestigious awards in literature and the arts including the MacArthur Grant, also popularly known as the “Genius” grant, a Guggenheim Fellowship, and he has been a finalist for both the National Book Critics Circle Award and the National Book Award.

Hemon has now branched out into television and film work, writing episodes of the television show “Sense8” and co-writing the film “Matrix 4” with the director Lana Wachowski and science fiction writer David Mitchell; “Matrix 4” is due to be released in 2021.

Hemon is also a gifted essayist and opinion writer for the New Yorker, Esquire, The Paris Review, The New York Times and BH Dani in Sarajevo.

Well-known for his outspokenness on political and social issues, his forthrightness can often be found on Twitter as he dives into the commentariat with both feet. He writes regularly about the Balkans, growing Islamophobia in the West, genocide denial and the state of both Bosnia and Herzegovina and Europe.

Like many Balkan observers, Hemon has lately been reacting to the social acceptability of people like Peter Handke, the Nobel literature laureate and Slobodan Milošević apologist, and Jessica Stern, the author of a recent book titled “My War Criminal: Personal Encounters with an Architect of Genocide,” about her relationship with the convicted war criminal, Radovan Karadžić; Hemon describes himself as “exhausted” by her work.

He is notably harsh on media like the New York Times, who he accuses of promoting and reporting uncritically on Stern and Handke in a bid for “balance,” without taking a clear stance against Handke’s genocide denial and Stern’s humanizing of a man convicted of genocide, most notably in Srebrenica.

K2.0 talks to Hemon about the rise of genocide denial, the relationship between the Balkans and Europe, culture shift in the West, being displaced and his own work.

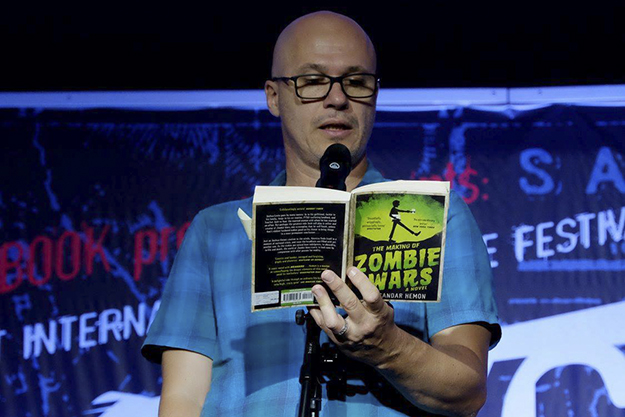

Photo courtesy of Bookstan Sarajevo.

K2.0: Ten years ago, most people wouldn’t have thought it possible that someone who denies the Srebrenica genocide would be awarded the Nobel Prize in Literature. What has happened over this last decade in the West to create such a fundamental shift in the culture?

Aleksandar Hemon: I think that in Western Europe and North America rabid Islamophobia has become mainstream and with it a belief that Muslims are so far out of the domain that defines and contains “Western values” that even the worst of their killers are closer to “who we in the West are” than their Muslim victims.

For many Western intellectuals and politicians, Milošević and Karadžić may have overdone the genocide thing a bit, but if they did, it was out of understandable fear that their people would be overcome by Islamists, which is what Muslims tend to become if let loose. This is, for example, Jessica Stern’s position.

For the Nobel Prize Committee, a thinker and author like Peter Handke is far more consistent with the great tradition of European intellectuals and Enlightenment then some Balkan Muslims who, they believe, contributed nothing to that great tradition and are now rotting anonymously in remote mass graves.

The implication is that for as long as there are Muslims around there will be a possibility of genocide.

Milošević shouldn’t have gone overboard, of course, but at the same time the Nobel Committee, Handke and Stern can understand that a European fearing Muslim invasion might lose his cool and slip into genocide. Both Handke and Stern treat their war criminals as “complex“ leaders who had to make tough decisions in a bad situation, but what made the situation bad in the first place was the growing presence of Muslims, who continuously play the victim card even if they brought the calamity upon themselves by existing in large numbers.

The implication is that for as long as there are Muslims around there will be a possibility of genocide. The way to avoid genocide is to properly eliminate Muslims — genocide prevention by way of final solution.

Many Europeans seem to look at the Balkans as a “semi Europe” or perhaps not European at all, while many in the Balkans seem desperate to be a part of Europe and see themselves as very European. This tension seems to be at the crux of the relationship between Europe and the Balkans. How does this become resolved?

I am of the belief that the wars in the Balkans were essential for conceptualizing the new Europe, providing a useful counterexample for the Union. In that framing, the Balkans is what Europe is not and never wants to be: The Balkans is cancer, and Europe is healthy tissue.

The European Union was going to overcome what the Balkans never could, and it never could because it was always insufficiently European, not least because of its ethnic complexity in general, and Muslim presence in particular.

Of course, those Balkan people may have overdone it, what with genocide and all, but they were dealing with the same difficult issues as proper Europeans.

But, at the same time, the Balkans resembles Europe enough to allow for projections, which became more pronounced as Europe started to deal, culturally and politically, with “the Muslim question.” Another way to put it is that Europe has pretended it evolved beyond nationalism, but with rampant populism and related Islamophobia on the rise, Balkan nationalism, once an expression of some innate savagery, suddenly made retroactive sense in Western European capitals.

Of course, those Balkan people may have overdone it, what with genocide and all, but they were dealing with the same difficult issues as proper Europeans. The Balkans is just close enough to being Europe to keep perpetually failing at being Europe.

I am reminded of Peter Handke claiming that Serbia is the purest Europe. But, of course, he lives in the suburbs of Paris.

I suppose the way to resolve the tension is to accept — intellectually, culturally and politically — that the Balkans, including its Muslims, is Europe, and has always been Europe, and will always be Europe, and that the Western European fantasies of political and intellectual superiority are deeply rooted in colonialism and racism.

But I don’t think that Europe is capable of that. It is as wedded to its fantasies of greatness as America is.

There is a kind of societal arrogance in America that is indistinguishable from delusional belief in the transcendent, eternal American essence.

It seems the West looks down at Yugoslavia’s breakup and says: This can never happen to us. You have said in the past: “To imagine the unimaginable is obviously not possible but it is the unimaginable that changes the world, not the imaginable.” Is the unimaginable happening now in the West?

What is happening now is what has always been possible but people refused to imagine it out of intellectual laziness and/or sheer fear. Thinking that shithole Balkan countries may fall apart but the United Kingdom or the United States are forever is a symptom of a terrible complex of superiority, which is a residue of a squandered imperial past.

There is a kind of societal arrogance in America, for instance, that is indistinguishable from delusional belief in the transcendent, eternal American essence that inoculates the Republic from a Yugoslav kind of failure. Well, Trump has torn that fantasy to shreds.

I remember various Americans expressing, after the elections, their belief that “checks and balances” will prevent Trumpian devastation. Every single level of “checks and balances” has failed at least once since then. Presently, the Senate has effectively given a go to Trump to do whatever he wants without consequences.

The possibility of a widespread and multilayered conflict, including possibly an armed one, which might lead to de facto — or even de jure — disintegration of America is so frightening that few people dare imagine it, let alone what might be beyond it.

Not long ago, it was just as unimaginable that the UK might come apart, or that various European countries might in fact keep migrants in detention camps where they’re deprived of basic care and human rights.

Much of your work focuses on your personal experience as a displaced person. Many people in this region have similar experiences where they or their families or both have been forcibly moved either by war or because of economic reasons. How does this affect Balkan societies culturally and politically? Are these societies broken forever by this? Or can they come out richer as a result?

I don’t think that having a quarter or more of the pre-war population displaced can in any way help Bosnia, for instance. As far as I know, there is a steady decline of population in Bosnia — and those people, mainly young, are on the move, heading somewhere else.

Migration generates narratives, because movement through human space means that experience and knowledge not only travel but are generated on the way.

I suppose that a stable population is a prerequisite for a society and a state that contains it. It is also important to understand that displacement is always a consequence. What broke the Bosnian society was the war, which caused displacement — indeed, displacement of populations was the main goal of the war.

But now that the people are displaced, it is hard to reconstitute a society. With all that, I retain hope that the diaspora has agency and ways to change outcomes in the homeland, as well as in the hostland. I also believe that migration generates narratives, because movement through human space means that experience and knowledge not only travel but are generated, as it were, on the way.

Do you still see yourself as a displaced person? Or have you now “placed” yourself? And do you see yourself as being from an extinct society? Or does it still exist somewhere?

Once displaced, always displaced. Displacement means that there is no place to return to. Displacement changes the way one thinks of everything: of oneself, of language, of home, of the world, of justice, and that change in thinking is irreversible. I am often asked if I wonder what would’ve happened if I had been in Sarajevo for the siege and the war. I do, all the time, even if I know that there is no point to it.

But imagining those alternative lives is always a failure, because there would’ve been so many possible trajectories. The point is that I could never return to the space and time where those trajectories were in fact available to me — displacement foreclosed them.

Hemon’s latest book explores issues of identity, a common theme in much of his other work. Photo courtesy of Farrar Strauss Giroux.

Moreover, displacement is not a moment — it keeps unfolding, and not in predictable, progressive ways. I feel far more displaced today, in Trumpist America, then 10, 15 years ago, even though I was nowhere near being placed back then.

Some 15 years ago, one of my closest friends from Sarajevo was getting married in London, UK, so I went to the wedding. Other than some locals, most of the other attendees were from Sarajevo as well, about 50 or so, but now they lived in Montreal, Geneva, Toronto, Zagreb, Belgrade, etc.

A few were close friends, some were good friends, some merely acquaintances, some I never even really liked. Yet, I had this epiphany: If all these people lived in the same place — Sarajevo, London, Chicago, Auckland, Addis Ababa, anywhere — I would move there tomorrow. But there was no such place, and there never will be.

A society is an abstraction, it only exists and is actualized in contact with other people, and most of human contact takes place in your immediate surrounding. So that if some are displaced, all are displaced.

Can you tell us about your work on “Sense8” and on “Matrix 4.” And with the Wachowskis and David Mitchell. I don’t think before “Sense8” many people thought of you as a science fiction author. And what did you find very different or similar to working with an author like Mitchell compared with writing alone?

I’m still not a science fiction author. The joy of working in cinema in general, and with Lana Wachowski and David Mitchell in particular, is that it is collaborative, that the whole endeavor of authorship operates entirely differently. When I write a book, every single word in it is mine and I decided to put it in there and they all came out of my imagination and/or experience.

Photo courtesy of Bookstan Sarajevo.

In cinema, including screenwriting, other people are always present — intellectually, imaginatively, emotionally, physically. You make absolutely nothing by yourself. This is both limiting, for obvious reasons, but it is also incredibly liberating — minds are joined and expanded to imagine something that none of them could imagine alone.

Lana and David are masters of creating different worlds, and I’ve learned so much from them about the ways to envision what is beyond my experience. It helps greatly that I love them as people and consider them close friends. I cherish every moment I’ve spent with them making up stories and human lives and futures. I’ll never stop writing literature, but I long for being with them in the imaginative pit every day of my life.

How was the transition to working on film and television for you?

It was not a transition, it was an addition. I had to learn to collaborate and anticipate contingencies, and had to reduce my dependence on language to tell stories. But other than that, stories are stories.

Does science fiction give you a chance to reconsider our world in a different way? To imagine the unimaginable in a positive way?

We’ve never started a project thinking: Let’s do science fiction! We do stories, and they take place in worlds somewhat different — but not fundamentally — from this one. One of the beliefs that bonds us is in the idea of storytelling as an undertaking that has epistemic value.

Storytelling generates, transforms and transmits knowledge by way of imagination as activated in language and/or cinema. That is also to say that on the inside storytelling is experienced as a discovery.

Example: In a script that has not found a home yet, we imagined what the disintegration of America, taking place over one generation, would look like. We spent time imagining the future much of America refuses to imagine. Perhaps that’s why the project is still homeless.K

Feature image courtesy of Bookstan Sarajevo.

This conversation has been edited for length and clarity. The interview was conducted in English.

The credibility of one's statement is a condition of the public word. But credibility is gained not by words but by actions. To write publicly better to say criticize the Nobel Prize laureate in literature is a challenging task. Especially when it is done by a well-respected and award-winning writer, as this article claims. To be a judge to the people he came from and descended from is also a risky business. In both cases, any statements, whether written in his literary works or uttered in the public media, must be based on facts, If it wants to be credible. So far, I have not found it in the above spoken and written words. Whatever may be a good intention. I did not find honesty in it, but the ordered texts of those who pay it well. The point here is not whether Hemon is right in claiming that Handke is a a writer-criminal ( lets be judged by others more qualified than me) or that the war in Bosnia and ex Yugoslavia was only black and white (with only good and only bad nations in the lead roles, which he persistently portrays and markets in his works), but rather whether he has the credibility to make such statements. It is also known that Hemon was one of the main actors in the famous incident of a birthday Nazi party in Sarajevo in the mid 80's. It is not easy and for no reason at that time to wear a Nazi uniform in socialist partisan Yugoslavia ... Out of protest? Against whom? Hemon never explained this, never felt the need to apologize for his actions to the people whose hundreds of thousands members were killed by the Nazis, except in his novels describing it as mischievous joke. And now let's ask ourselves: if this hated criminal Handke did the same in his native Austria, where would he end up? But, Hemon profited from that ... So, I don't think Hemon has the credibility to give moral lessons to anyone, let alone the Nobel laureate, unless there are facts about it.