In the summer of 1975, two Scandinavian women in their late twenties met in the seaside city of Durrës, Albania. Ann Christine Eek, a Swedish photographer, and Berit Backer, a Norwegian anthropologist, hadn’t known each other before. Drawn by common interests, they decided to embark on a joint research project: a photo book that would document everyday life in Isniq.

Backer had already started ethnographic fieldwork in Isniq, a village in western Kosovo that sits in the shadow of the Accursed Mountains. She and Eek spent much of the summer of 1976 there immersed in village life, and then left with thousands of photographs, video recordings and warm friendships with the people of Isniq. But once back home in Scandinavia, Eek told me, “Everyday life kind of killed the project for a while.”

Alongside her anthropological work, Backer was a leftist political activist in Oslo and was deeply engaged in issues relating to migration and Albanian political prisoners’ rights in Kosovo during the 1980s, working for organizations such as Amnesty International, International Helsinki Federation (IHF), and the Norwegian authorities. In March 1993, she was tragically murdered by a Kosovar Albanian refugee in Oslo who was suffering a psychotic break. Her anthropological study on household organization in Isniq was published as a book posthumously with the title “Behind Stone Walls.”

Forty-five years after Backer and Eek’s work in Isniq, Eek — who had an extensive career as a photo reporter and photographer at the Museum of Cultural History in Oslo — has returned to her photographs from Isniq. In Fall 2021 the book, “Albanian Village Life – Isniq, Kosovo 1976,” edited by Eek and Tahir Latifi, an anthropology lecturer at the University of Prishtina, was published in English and Albanian by Tira Books in Sweden.

At over 250 pages, the book is an intimate visual chronicle of rural everyday life in mid-1970s Isniq. Depicting women, men, children and the elderly while they work, prepare food, chat, dance at a wedding or mourn their loved ones, Eek’s black and white photographs capture the people of Isniq with their full richness. In a review of the book, sociologist Anna di Lellio called it “a remarkable work of visual anthropology.”

A woman and son in a shepherds’ camp. The barrels are for storing bulmet (dairy products) for the winter. Pleqe, Isniq, September 1976. Photo: © Ann Christine Eek.

Alongside the photographs, Eek gives detailed recollections of her and Backer’s interactions with the people of Isniq — with whom she still has close contact — and historical accounts of life in 1970s Kosovo.

In 2019, Eek’s photographic work in Isniq was displayed in an exhibition at the Gallery of the Ministry of Culture, in Prishtina.

K2.0 met with Ann Christine Eek via Zoom to talk about her photography, the time she spent with Backer in Isniq and her unceasing search for the right composition and light.

K2.0: In the book, you describe your first meeting with the Norwegian anthropologist Berit Backer in Durrës, Albania in the summer of 1975. It was there that your friendship with her began and you planned a joint photography project in the village of Isniq. Why were you in Albania?

Ann Christine Eek: At the time, I was working as a documentary photographer. I had made a book about women who worked professionally while also taking care of their children and families. It was titled, “Work — don’t wear yourself out!” When I published it, a friend of mine said, “Why don’t we try to go to Albania and see if we can do some rapportage there?” But we never managed to.

I ended up traveling there with a group from Sweden and Norway. The trip down took an incredibly long time. We had to wait at the border until it was dark because we were not supposed to see anything on the busride.

We arrived at about 11 o’clock at night. We hadn’t had food for about 18 hours and people were getting crazy. I managed to find who was responsible for the arrangements. It was Berit Backer and she was just fantastic. I mean, at 11 o’clock at night she had managed to open the kitchen and fix food for about 40 people.

We started talking and it turned out that her father had been a photographer. She told me she was an anthropologist, but she took a lot from her father. I asked her what she had been doing and she told me about her fieldwork in Isniq — she was about half way into it. I had heard a radio program some months ago about extended families. There was a Croatian reporter who went with some Swedish people to this village where you had this family of about 105 people. So, I kind of understood what she was talking about, though there were not such big families in Isniq.

I asked her if we could go and make a book together. I knew nothing about Kosovo at the time, almost no one knew anything about it. And no one talked about Kosovo in Albania. It was kind of a new world that opened up to me and I started to prepare myself by reading. I got Edith Durham, Margaret Hasluck and some other authors, but it was all so new to me.

When Berit was back in Norway in January 1976, I went there to spend New Year’s Eve with some friends and I met her. We started talking, planning and trying to find out how to finance the trip. Back then I lived in Stockholm, in Sweden, and she lived in Norway. But I had friends in Norway, so I came here quite often. Berit and I did a lot of back and forth trips. She came to Stockholm, I went to Oslo and finally we managed to get a contract with Swedish television. They wanted us to make a film. However, that film is full of mistakes and incorrect facts, so let’s just forget about it [laughs].

Can you talk a bit more about the film? Why was it full of mistakes and what has happened to it?

I think because Berit had not started to write her thesis yet. She had been in Isniq for a year, walking around and talking to people. It was difficult for her to get into the oda. She needed to hear the men’s discussions about the economy and politics. I think she wrote somewhere that she managed to take part in just five meetings in the oda. So after the film was done, when she was writing her thesis, she realized that there were mistakes in the film. Also, we exposed a bit too much information about some people and she had friends in Isniq who were really furious with her because of that. When I started writing this book, I looked through the film and I said no, let’s just forget about it.

When the men were away, working outside the village or abroad, women took over heavy agricultural labor. Isniq, September 1976. Photo: © Ann Christine Eek.

But also, technically, the quality of the color film was not good. I’ve been trying to digitize it, and it’s extremely bad. I worked in color for this film because the Swedish television station said that people have a tendency to turn everything black and white when they go abroad. At that time, I was not a good color photographer.

In 1992, when I went to Albania for the second time, I was showing some photographs to friends at a meeting. I had some color photographs and some old black and white ones, and they said, “How can you, who are such a good black and white photographer, be such a lousy color photographer?”

Working in the field, particularly in the 1970s, with very simple color film, was not easy.

Are all the photographs you took in Isniq, in 1976, in black and white?

No, about 30% were color photographs that I converted into black and white. I prefer to work in black and white because when you work in color there always happens to be someone in an orange coat passing by in the back. There’s always some color that disturbs the whole thing. And for me it’s very important how I use the light, and the composition — how you place people in the picture, movement, directions. I focus on people’s eyes, on what they’re looking at. When I work in black and white, I can concentrate on those and skip the colors.

How did you play with the composition in the Isniq photographs? Most give a sense of spontaneity, letting the viewer experience the atmosphere of the moment.

Some of the photographs, where people are sitting, for instance, are arranged. People often had an idea of how they wanted to be photographed. One cliche is three or four people standing beside each other looking at the camera. They had this notion of how they should be standing to be photographed. Because I was speaking Albanian very poorly at that time, I couldn’t follow much of what people were saying. I think the women more or less gave up trying to talk to me, and Berit handled all the conversations. I just walked around and followed what was happening.

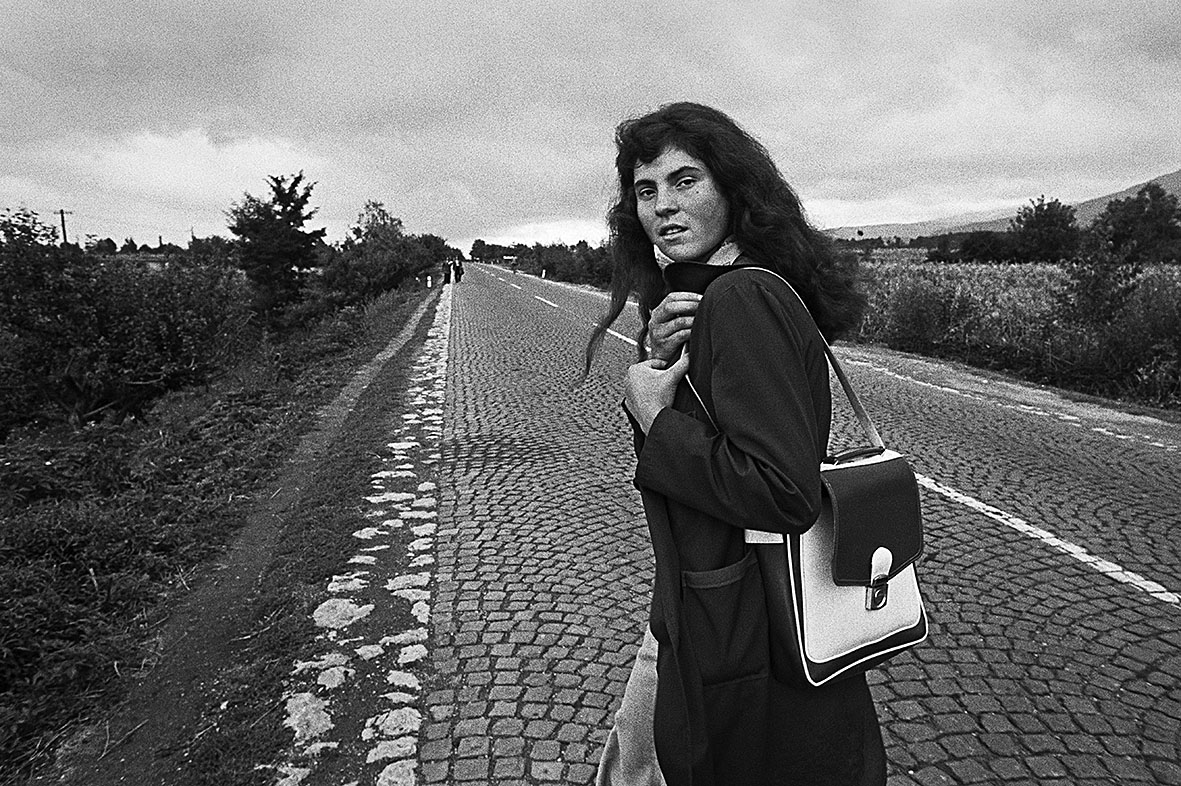

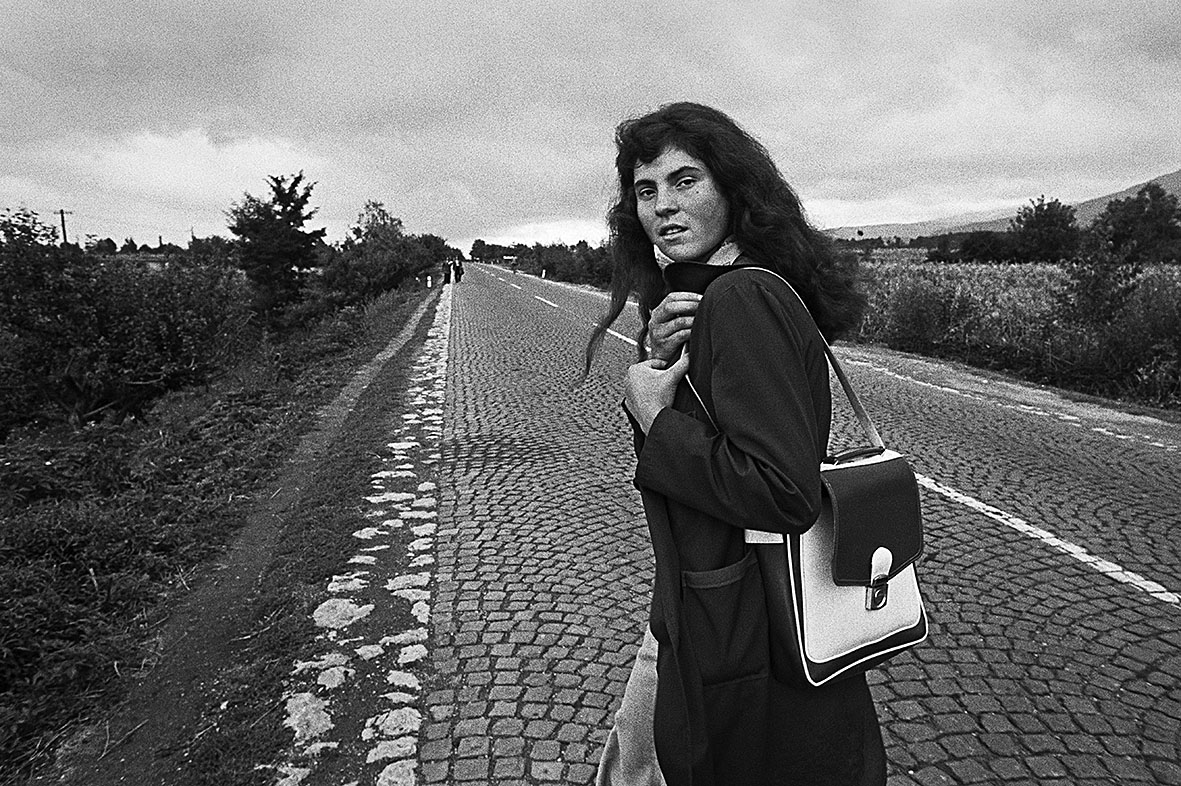

Nushe, a village girl on her way to secondary school in Deçan. September 1976. Photo: © Ann Christine Eek.

The photographer Henri Cartier-Bresson talks about the decisive moment. It’s kind of finding when you have the composition and the light at its maximum, and you get the most expressive picture. For instance, the cover photograph of the book is of a girl Nushe as she walks to school. I’m very, very happy with that photograph.

We were following her to school in Deçan, she was walking and I took a picture of her back and the landscape but I was not satisfied. So I said to Berit, “Please, slow down a bit,” and then I called Nushe, “Nusha,” and she turned, and I took the picture.

Why did you decide to have that one as a cover photo of the book?

I think because it is a very positive picture. It kind of points towards the future. And she was a very positive person. She was walking forward and there was the empty road and the empty fields. I like that very much. I’ve been back now several times to Deçan and the whole area is full of buildings, I can’t even find the spot.

How did Berit Backer initially decide to come and conduct academic research in Kosovo?

She went to Albania for the first time in 1969 in one of these groups, because she was in a left-wing group here in Norway. She started reading very early about Albanians and was fascinated. She wanted to do research in Albania but she was not allowed to.

At that time, she was studying in Bergen, and a professor there said to her, “if you can’t go to Albania, why don’t you try to go to Kosovo?” So she applied and arrived in Kosovo in the autumn of 1974. She stayed at the University of Prishtina, which was quite new then. I’ve seen a short text she wrote about living there. It made me understand why the students were so upset in 1981 because already then she described how the girls who came from poor families had to stay in cramped dormitories where often two girls were sharing a bed.

When she went to Isniq she had heard about this patriarchal society so she was a bit anxious about approaching men on the street and talking to them. She had this small flat in the old school building and villagers thought she was just sitting there and writing a book and no one really talked to her. One of my friends, Bajram, who is not with us anymore, was the first one in the village who invited her home to his family. Downstairs from her flat in the school there were two families, the Kuklecis and the Tahirsylajs and she was more or less adopted by the Kukleci family.

You write in the book that it was a bit more difficult to photograph men and enter the spaces specifically designed for them. Can you talk about this?

It was okay to photograph them outdoors, working in the fields, or the shepards up in the mountains. Similarly, it was no problem to photograph men in the shop standing around or chatting. But what Berit wanted was to be able to sit down when the men had their discussions on economics and politics and things like that in the oda, where all the males, from small boys to old men were together. And we weren’t allowed there.

Berit had trouble understanding how the local economy worked. She really needed to be present to understand what people were talking about. And I really needed some photographs of men sitting together. Towards the end of our stay we had been in the mountains and we came down and we were told there was going to be a funeral in one of the big families. There were so many women [in the mourning ceremony]. We were so amazed to see it, the whole performance was just incredible.

Newlyweds in the bridal chamber of the family house, decorated with textiles from the bride’s trousseau. Isniq, August 1976. Photo: © Ann Christine Eek.

We knew that the men were in the next door house, which belonged to the same family. Late at night we had dinner with the women and then Berit and I tried to get in. I prepared my cameras and then we just crashed in. The men were sitting and eating and our host Selim Kukleci was there. He was really furious with us. So he chased us out right away but I managed to take a few pictures [laughs]. It’s not really the proper way of doing things, I am very much aware of that, but it was our only chance.

For me, some of your most expressive Isniq photographs are the ones you took during a kanaxheq (the women’s pre-wedding gathering) and a wedding day. Can you talk about the atmosphere behind those photographs?

Berit and I went there with our hostess Cyma Kukleci. I just had my cameras, I didn’t know what it would look like. In one of the pictures I took there, all these women are sitting and looking at me. Maybe I felt as strange as the bride arriving [laughs]. I didn’t know what was happening. And they said “Oh, here is a photographer!” and they wanted me to take pictures of the bride and the bride groom in the bridal chamber. So I took pictures in which the couple is sitting on the bed and some other photographs. Then we went back to the room where the bride repeatedly changed into different dresses and would then return and stand against the wall. I was just trying to show what was happening in this room. It was not a very big room but lots of women were in there.

You mentioned that Berit and you planned to create a book together many years before. Why didn’t you manage to write it together?

We had planned to make a book, Berit and I. And for different reasons she had difficulties writing it. When we came back we made this film for Swedish television and then other things happened. I had to make a living and Berit had to make a living and she had to write her thesis. Then I came here to Oslo and after a while I got married and had children. Everyday life kind of killed the project for a while. I had these very, very good photographs, so by the end of the 1980s, I said to Berit, we need to do something. And she said, “You’re so good at writing, so you can do it all by yourself”. I said, no I can’t.

Then I was back in Albania in 1992 and I wrote some articles about traditional culture and things like that. She said it’s perfect, go ahead. But then, we sat down and started planning to continue our work. We thought maybe we should use the material from Isniq to make a comparison to women’s situation in Albania. I applied for and got a grant. Some days later, on a Sunday, we sat down to discuss the project and she was killed later that night.

I realized that very few understood the work Berit had done and I persuaded her family to give me her materials. I’ve got a lot of her stuff here. I’ve read everything she has written and published. I realized I was very naive, there was so much I didn’t understand or know. She had incredible knowledge of what was happening in Kosovo and she used every opportunity to go there to see friends. They had this ethnographic conference in August every year and she went several times and also maintained contact with different families and friends.

She also wrote reports for Norway’s Foreign Ministry and the Ministry of Justice and that was so fascinating to read because she knew so much about what was happening in Kosovo. In Norway people were very much in support of Serbia, people didn’t like Berit. They thought she was too positive about the Albanians, so she had difficulties. I remember in 1991, I worked at the Ethnographic Museum in Oslo, which is now called the Museum of Cultural History, and we decided to make an ethnographic exhibition there with some of my photographs. She wrote short articles for the catalog and she had to fight for every word to get published because people didn’t want to believe her.

I remember a man who visited the exhibition. He came from Isniq and was a refugee in Oslo. I saw this young man staring and staring at my photographs on the walls and he looked completely lost. I said to him, “What do you think?” And he said, “That’s where I come from.” He didn’t know what to say. He was spell-bound.

In the book you provide detailed accounts of the characters, events, and families that are depicted in your photographs. How did you manage to preserve all that information?

In some parts I draw from Berit’s work. But also the photographs are a great help to remember things. I wrote a diary in the first days but then I didn’t have the time to continue. Also, I have come back and spoken to people, and I think I have a good memory.

Woman baking pite (a pie), village Isniq, Kosovo, September 1976.

After Berit was killed I had big plans. I wanted to make a big book about Albanians. And I have around 30 or 40 thousand photographs. Many are good photographs that might be published. I didn’t have many notes, but when Berit was killed I sat down and started writing.

You mention a meeting you had with Albanian political dissident Adem Demaçi in July 2000. Can you talk a little bit about that meeting and why you came back to Kosovo then?

Demaçi had been here in Oslo, in connection to Berit’s funeral. He gave a small speech at the funeral and I also gave a small speech. Then he came back because he was involved in different political discussions here in Norway about the future of Kosovo and every time he came he wanted to meet Berit’s mother and he wanted to see me.

He got a peace prize [Leo Eitinger Prize for Human Rights by Oslo University] in 1995 and he was staying for quite some time here in Oslo. So I went to see him many times. And also when I came to Prishtina in 2000 we spent the whole day together. Last time I met him was four years ago in 2018. Berit was awarded this decoration from President Thaçi and we had a dinner where Demaçi was invited. That was the last time I met him. He was a very very nice person. We just enjoyed being together and talking about a lot of different things. I can’t write any deep thoughts about Demaçi as a politician because I don’t know enough about that, but I knew him as a friend and he was a very lovable person.

What was the political atmosphere in Kosovo, particularly in Isniq, in 1976? What could you understand about politics from the everyday life of the people?

People didn’t want to talk about politics in the village. And also Berit and I understood it was a very difficult situation. For instance Demaçi was on trial. I didn’t know who Demaçi was back then, in 1976. But we had read in a newspaper that he had been on trial and we knew that the situation between Albanians and Serbs was very difficult. We could sense it, for example, when we went to the market on the bus together with Albanian women and people really looked down on us, saying, “You shouldn’t be together with Albanians.”

Gradually we understood that the situation was very dangerous. We hadn’t applied to the Yugoslav authorities for permission to do the research. We came as tourists. Berit said all the time that when we go to Prishtina she was going to talk to Ukshin Hoti [professor of international law at the University of Prishtina and secretary of foreign affairs at that time] about this. He had helped her initially when she first arrived in Kosovo. But he was never in his office. So it was five weeks before she finally met him. I was sitting and waiting at Hotel Bozhur when she came back. She was completely gray in the face. She said, “He didn’t like what we did at all and it’s a very dangerous situation.” So we went back to Isniq and we packed everything and tried to leave as quick as possible.

I think he was worried that something might happen. Berit was in contact with a lot of foreigners in Prishtina and suddenly they started talking about ethnographers who had been studying this and that and were thrown into jail for no reason at all. We started to feel really scared. The plan was to have a car, but we had a car crash in Montenegro on the way down, that’s why we had to travel by bus all the time. So when we went back to Isniq, we rented a car to go to Shkup to take the train back home. We were so happy when we passed the border and we were in Austria.

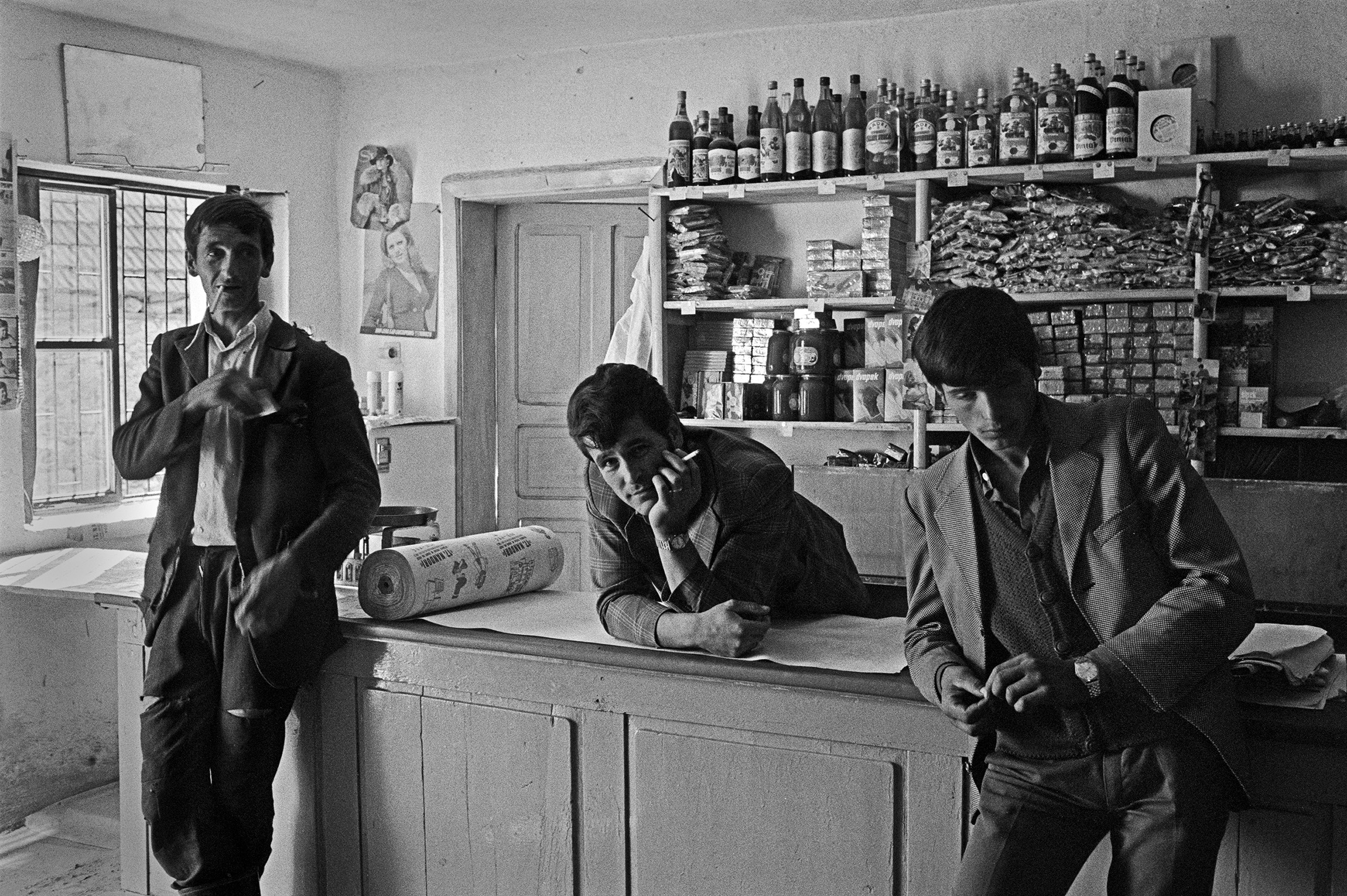

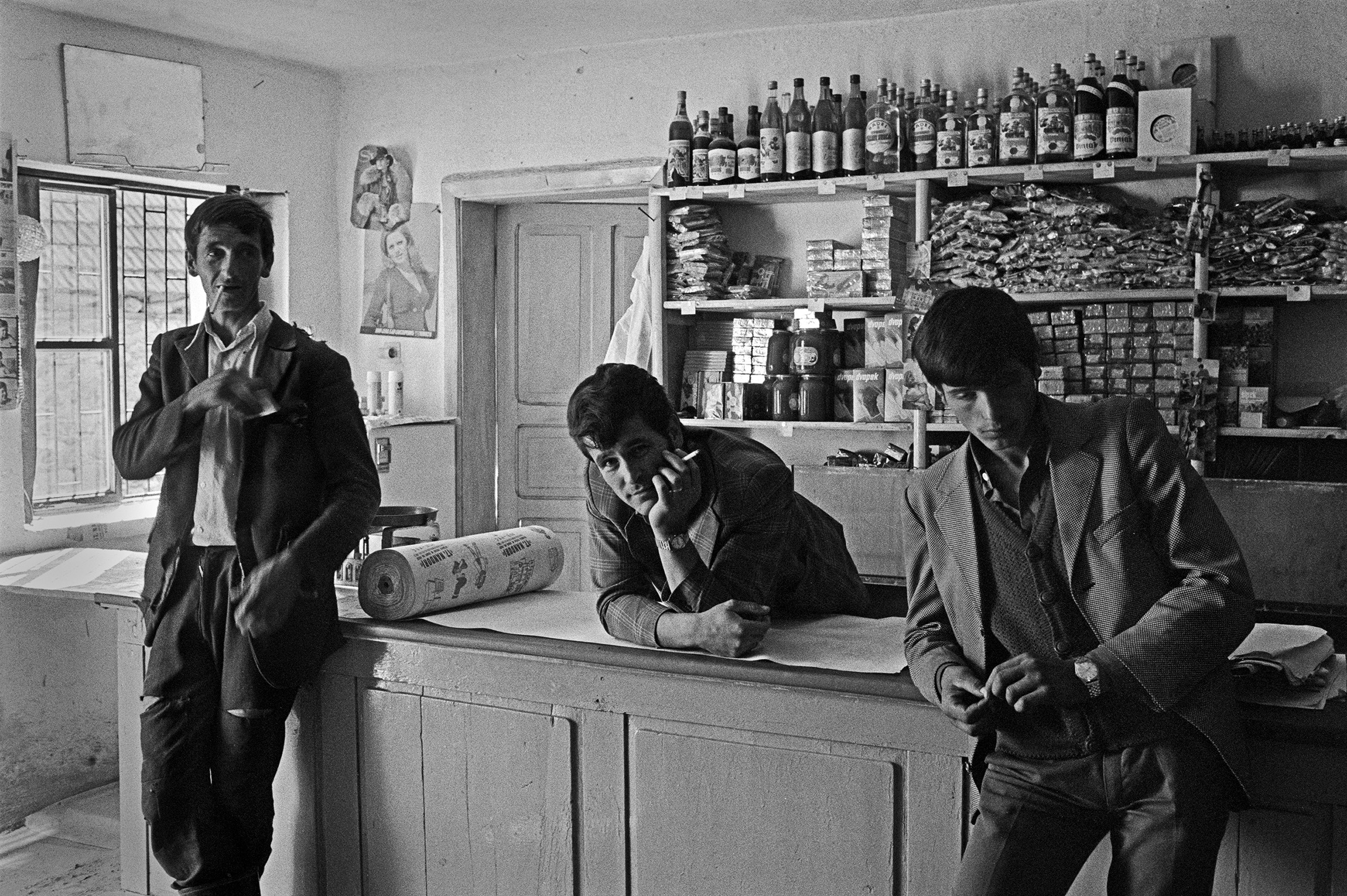

From your Isniq photographs I particularly like the one in which three men are standing inside a village shop, each of them looking in different directions, all with melancholic looks on their faces. Can you describe the moment when you took that picture?

I had entered the shop and taken some pictures just before I took that one. There were some children peeping by the door. I took a photo of them first. It was so fun with those kids, they were so curious. We wanted to talk to the guy in the middle because he had built a new house and we were invited to see it. I think I just stay open to things I see and I photograph.

Men out of work spending time in one of the village shops. Isniq, Kosovo 1976.

I wait for moments when I think it works — when you have the combination of light and composition. Like in this picture in the village shop — the position of the men, the background showing the scarcity of things they were selling in the shop. So, I just took a picture.

Were you content when you saw the photographs for the first time after you developed the films?

I don’t know. I thought I had done some really big work, but it was difficult for me to understand the scope of what I had done. At that time, I was working in a photographers’ collective in Stockholm and none of my colleagues were particularly impressed with my work. It took me a long time and many, many hours in the dark room to understand the potential of this material. Gradually, I understood what I had photographed. And what happened during the war made me realize how important this work was.

Are you working on any projects right now?

I was much more active as a photographer before. I worked for many years as a photo reporter. Then I had all these years where I worked at the museum which was both studio work and a lot of administrative things. I’ve been working very much with landscapes. There is a river dividing Oslo in two parts and I live 50 meters away from this river. I take a lot of walks and I’ve taken a lot of photographs of that river. Hopefully I’ll be able to make an exhibition or a book with my river photographs. I’m getting a bit older and I realize I’m not as quick with my legs as I was so I don’t have any particular project going on right now. I go for long walks and I bring my camera with me and see what appears. I think this book about Isniq is the most important I’ve done.

This article has been edited for length and clarity. The conversation was conducted in English.

Feature image: Ferdi Limani / K2.0.

This article has been produced with the financial support of the “Balkan Trust for Democracy,” a project of the German Marshall Fund of the United States and the Norwegian Ministry of Foreign Affairs. Opinions expressed in this article do not necessarily represent those of the Norwegian Ministry of Foreign Affairs, the Balkan Trust for Democracy, the German Marshall Fund of the United States, or its partners.

Why do I see this disclaimer?