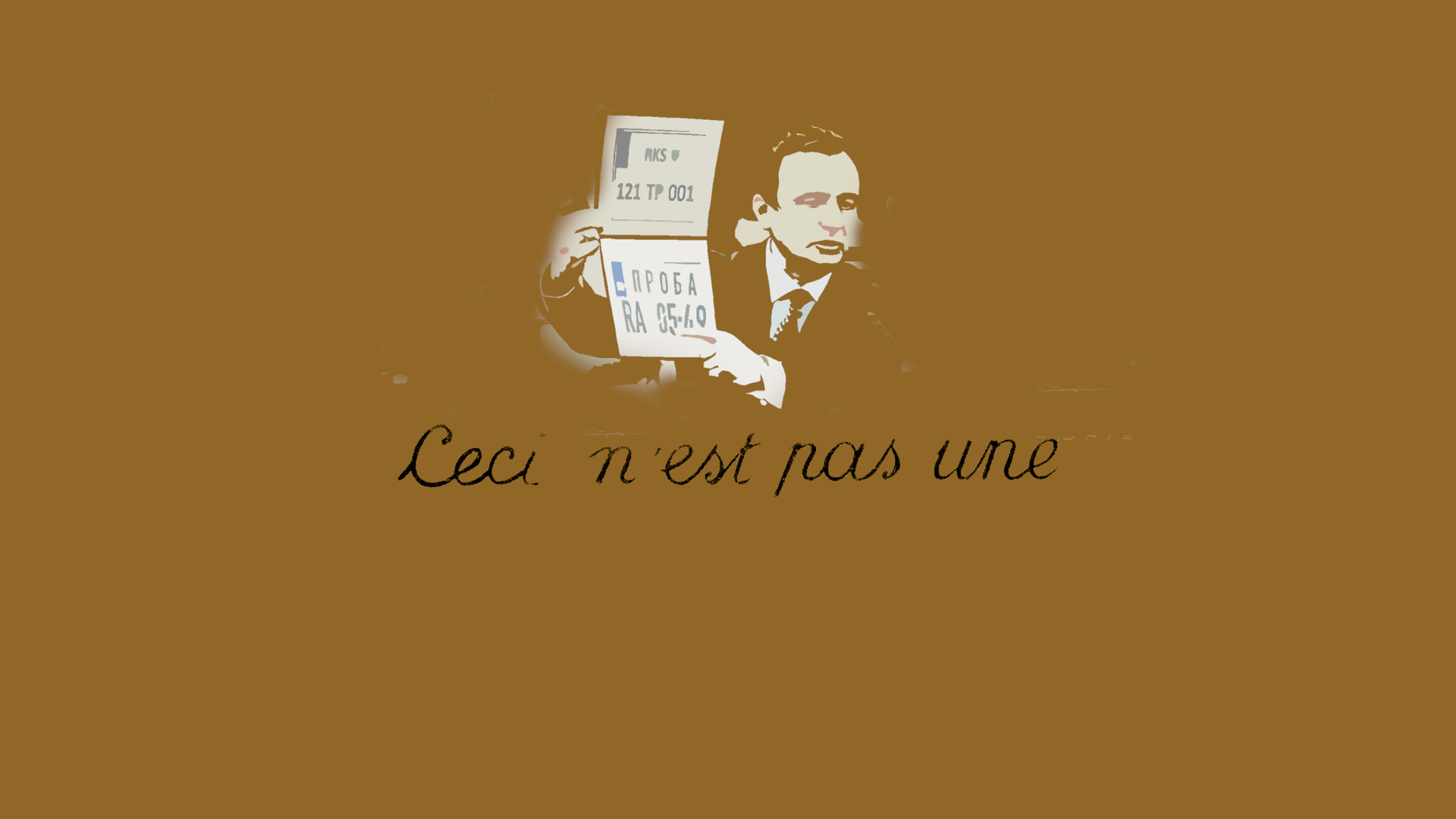

Ceci n’est pas une license plate

This is not a license plate.

Kurti is tied to a statist notion of sovereignty that is organized around borders, military force and other masculine aspects.

When Kosovo attempts to act as an equal, Serbia sees an act of provocation.

The dialogue has been a performance primarily about the EU itself and the image it wants to portray to the world.

Vjosa Musliu

Vjosa Musliu is Assistant Professor at the Department of Political Science at the Vrije Universiteit Brussel (VUB).

DISCLAIMERThe views of the writer do not necessarily reflect the views of Kosovo 2.0.

This story was originally written in English.