Even prior to WWII, the Kingdom of Yugoslavia had established itself as a significant European nexus of the comic genre. Influenced by the culture in the U.S. and Europe, a number of magazines and annexes were introduced, featuring jokes and comics.

Those comics were often republished Western pieces, but this momentum also enabled local artists to publish their original work and establish themselves on the scene. The 1930s are considered to be a golden age of the Yugoslav comic culture, and a number of Yugoslav artists saw their comics republished in Western Europe, often in France.

WWII put a halt to this golden age, and the rigid communist period immediately following the establishment of socialist Yugoslavia saw comic books banned. However, after breaking with Stalinism and forging a path independent from the USSR, Yugoslavia saw a period in which the laws governing cultural production were much more relaxed. In the late 1950s, a number of new magazines emerged and the comic book genre rose to prominence, occasional brushes against censorship notwithstanding.

Despite being far away from the cosmopolitan cultural centers of Belgrade and Sarajevo, Kosovo was not immune to these trends.

While the distance translated into a delay of about a decade, the comic genre slowly rose to existence in Kosovo during the ’60s and ’70s as well. Panels in daily newspapers and comics that were published — mainly in other parts of Yugoslavia — influenced the comic book subculture in Kosovo.

During this period, pioneers such as Agim Qena, Ramadan Zaplluzha and Gani Jakupi began to make their names, through comic strips published in newspapers such as Qena’s “Tafë Kusuri” or Zaplluzha’s “Therrë Murrizi.”

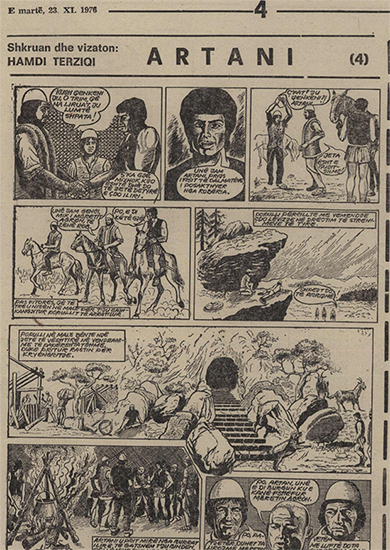

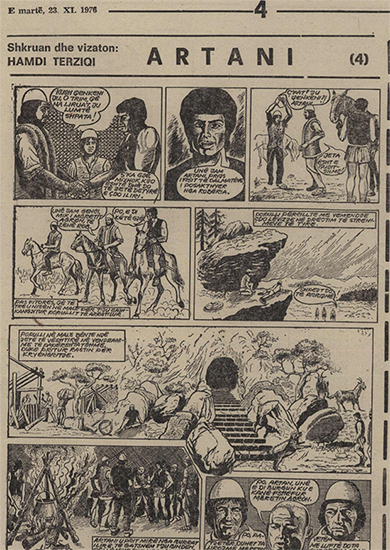

Excerpt from Hamdi Terziqi’s “Artani.”

The caricatural genre also blossomed during this time, also due to the art by Qena and Zaplluzha as well as by other pioneers, such as Nexhat Krasniqi, Veli Blakçori, Selami Taraku and Musa Kalaveshi. The early generations would influence those who followed, with Jeton Mikullovci, Visa Ulaj, Murat Ahmeti and Shpenda Kada later becoming familiar figures.

Many of the early cartoonists published their comic strips in the only Albanian language daily newspaper in Kosovo, Rilindja (Rebirth). However, after Rilindja closed its doors, they sought other opportunities to express their creativity.

This would come in the form of publications such as the Strip Arti magazine, the first Albanian language magazine entirely dedicated to comics, and Hapi Alternative in the ’90s — the editor of which, Petrit Selimi, would go on to open the Strip Depot café in Prishtina, an alternative space where one could read and buy comics.

In the early post-war years, the source of comics for Kosovar enthusiasts were the annex for children, Vizatori, of the daily newspaper Koha Ditore, the children’s magazine Hareja (Joy) published by the renowned journalist Ibrahim Kadriu, and the aforementioned Hapi Alternative.

Tafë Kusuri

One character that became a household name in Kosovo for 30 years was Agim Qena’s Tafa, a naive, easily confused, middle-aged Albanian man, who Qena used to devise sharp-witted criticisms of the state of society and politics.

Agim Qena continued to publish “Tafë Kusuri” at Koha Ditore all the way until his death in July 2005. But Tafa, the character Qena created, lived on for a while: Agim’s son, Rron Qena, continued to publish “Tafë Kusuri” for several years after after his father’s death.

“Agim’s journey was difficult,” Rron begins his recollection about his father. “At a very young age, he began to work with caricatures, a profession that requires you to read a lot, in order to be successful in it,” he says, going on to explain that Agim invented the character of “Tafë Kusuri” when he was 20 years old.

“It was a job that enabled him to create, but also get a salary,” Rron says. “He made a name for himself with his comics and was able to convey the messages of that time with few words in a satirical way.”

He adds that Agim was also fond of painting, but could not make a living out of it.

Furthermore, Rron explains how he entered the world of comics and continued his father’s creation. “After Agim’s death, since I was his inheritor because I was also his student in drawing and painting, I attempted to carry on “Tafë Kusuri” in Koha Ditore and I worked for five years trying to stay true to Agim’s line,” he says.

Excerpt from Agim Qena’s “Tafë Kusuri.”

After this period, he decided that he did not wish to continue.

“I was bothered by the fact that I had to read newspapers and that every day I had to hear about the idiocy spoken by politicians,” Rron says. “This aggravated me spiritually. Compared to painting, comics seemed difficult.”

Rron recalls that Agim had told him a very young age to work with paintings producing comic strips on currents on a daily basis was a heavy burden. “He would say that [painting] is ‘a bitter piece of bread,’ but that I had so much talent,” he says. “He told me not to work with caricatures.”

He says that comic book culture was nonexistent among Kosovo Albanians. “Fortunately, we had Agim Qena who made short comics, but we had no one who attempted to create something longer,” he says. “In the ’90s, we started to read comics from around the world since Serbs translated them, and at that time at least residents of cities read comics.”

‘A picture is worth a thousand words’

Gani Jakupi is another Albanian comic book pioneer. Jakupi says that he made his first comic when he was just eight years old. At the age of 13, he drew a three-page story that was published in a children’s magazine called Pioneri (Pioneer).

Jakupi says that he was inspired even before he encountered comics.

“I was born in the village of Gollak and when I discovered images, my general interest for art was ignited,” he says. “Before I started primary school, I learned to read as an autodidact, through comics. At the same time I learned the Serbo-Croatian language, since publications of this kind were only published in this language at the time.”

Thinking back to the early days of producing comics, he says that the only person to draw comics before him was Ramadan Zaplluzha and that his publications were “rare and amateurish.”

Excerpt from Ramadan Zaplluzha’s “Lirimi.”

Jakupi stresses that comics have an important function, citing a saying dating from 600 BC, when Confusius said that “a picture is worth a thousand words,” but adds that this was an arbitrary proposition.

“Surely he considered that verbal discourse has to be decodified to be understood — words can express opposing notions depending on the context, but also on the culture,” Jakupi says.

“The visual world communicates directly with our brain by providing a series of endless information. There are prose pieces that have more meaning than visual pieces. Poetry can arouse the imagination more than graphics.”

The benefit of visual art, he explains, is that written art demands considerable interpretive strain from the reader, whereas images communicate immediately with every person.

In his teenage years, Jakupi published comics in just about all the media that existed at the time in Kosovo, and later on in the many different Yugoslav republics.

Storytelling through images can serve as a propaganda weapon, an educational tool and as an entertainment tool, Jakupi says. He explains how the origin of Western art lies in the necessity of Christendom to make their message more accessible for the uneducated, illiterate masses.

“Soviets emphasized the film industry as a propaganda industry, whereas Hollywood sold the American Way of Life to its population and then to the entire world,” he adds.

Jakupi says that comics find themselves in this configuration as a more dynamic genre compared to paintings, and are more economically accessible than film. “Unlike other communist regimes, who considered comics as an eventual conveyer of democratic or Western values, Mao’s China emphasized this form of art with objectives that were the same as those of the medieval church: to impose its ideology onto partially educated masses,” he explains.

In the late ’70s, Jakupi began to visit Western countries and his journeys abroad gradually became longer. He travelled across Europe, mainly by hitchhiking, until he eventually settled in Paris. After a long period there, he moved to the southern city of Toulouse, and later to Barcelona, where he lives to this day.

In his teenage years, Jakupi published comics in just about all the media that existed at the time in Kosovo, and later on in the many different Yugoslav republics. In France, he had to start again from the beginning, at the amateur level.

“I published illustrations, a few short stories in fanzines, and eventually I managed to publish the ‘Matador’ series with three volumes, in collaboration with French painter Hugues Labiano, who was the screenwriter,” he says.

Unfortunately, despite the success among critics and the public, he came into conflict with the editor, who claimed that his style was closer to genuine literature rather than simple entertainment.

“In a way, I was way ahead of my time; my approach more so reflected the graphic novel genre,” he says. “Afterwards, I was in contact with other publishers who valued my work but the projects failed due to circumstantial reasons, so I decided to dedicate myself to other areas: illustration, design, photography, translation, journalism.”

When Jakupi returned to the French-Belgian comic book market, the graphic novel genre had enveloped the public and he embraced it, finding himself in it.

“From 2009, I worked for the most prestigious publishing houses, which enabled me to realize projects which I didn’t even dare to dream of before,” he says. He adds that his piece “El Comandante Yankee” is a good example, because according to him, no other publishing house beside Dupuis — which is part of the biggest European publishing group, Média-Participations — could approach such a voluminous project.

Jakupi works on projects over long periods. He spends more time researching documents and creating concepts for his pieces rather than actually drawing them.

“Recently, my work method has included personal interviews and research, so this makes the process even longer,” Jakupi says. “It is not illustrative, because it is a sui generis case, not only in my career but also in the history of the genre. I must note that the realization of the graphic novel ‘El Comandante Yankee’ took 12 years.”

Jakupi’s research was later published in a book titled “Enquête sur el Comandante Yankee” (La Table Ronde, 2019).

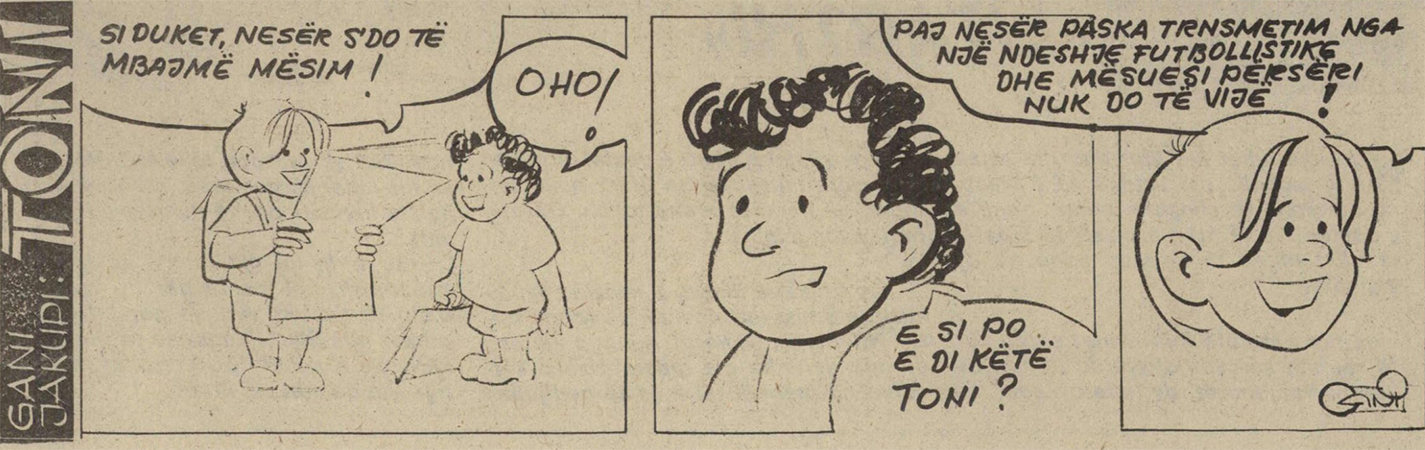

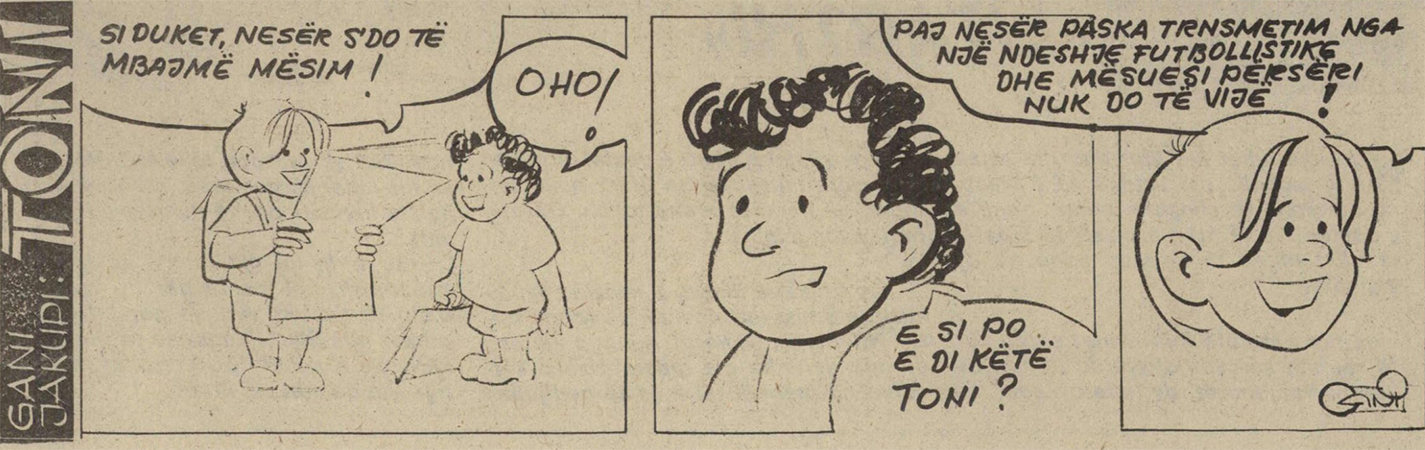

Excerpt from Gani Jakupi’s “Toni.”

Despite being away from his homeland, Gani Jakupi remained continuously engaged in the comic book subculture in Kosovo.

In May 2019, in collaboration with Jeton Neziraj and Agron Bajrami, Jakupi organized the first international graphic novel festival, called GRAN Fest. “We brought eight authors from different parts of the world, organized an exhibition with a selection of their pieces, and we translated and published the piece of our American guest, Tom Kaczynski,” he says.

Jakupi explains that this was a way to present a broad spectrum of different contemporary styles to the Kosovar public.

After the end of the festival, Jakupi returned to Barcelona where he continued to publish books. He says that he cannot judge the impact that GRAN Fest has had on the Kosovar public, but that the initial response was very encouraging.

“I believe that with the eventual continuation of the festival, with the publication of more autochthonous pieces and the translation of quality pieces by international authors, there will be public interest,” he concludes, adding that this requires work and engagement as well as support from local institutions.

The Pimpsons

Fisnik Ismaili, in addition to being a well-known war veteran, businessman, designer and politician, is also an author and fan of comics.

He recalls his first encounters with comic books at a very young age.

“I knew Serbo-Croatian, so when we got our hands on a comic, we would read it for sure,” Ismaili says. “There were pieces that were published in newspapers, but also special publications. There were about 15 or 16 special publications. They were from Belgrade, Zagreb and Sarajevo. There were none in Albanian.”

Ismaili recalls that there were only a few comics in foreign languages, which “were mainly published by Panini, and there was another publisher.”

However, a magazine that was important for his development was called Politik Zabavnik, a Friday supplement of the Belgrade daily newspaper Politika. Zabavnik (Entertainer) was a children’s magazine, which had all kinds of tales and comics.

He remembers the sci-fi story in the middle of the magazine. “It was the first time I encountered sci-fi,” he says. “That’s where I became familiar with Arthur Clarke. You also had the latest scientific discoveries, fun facts on the second page, and there were questions that scientists answered.”

On the third page was a two to three page comic, Ismaili says, recalling the contents of his childhood magazine. “If I’m not mistaken, it was Mickey Mouse. In the end there was Hägar the Horrible, Donald Duck and Dennis the Menace.”

He explains that he learned a lot from Zabavnik, which gathered pieces both for adults and children in “a perfect combination.” According to Ismaili, others tried to emulate the magazine, but no-one succeeded.

Ismaili’s grandfather in Mitrovica had a large collection of the magazines, which he would enjoy whenever he visited.

“There were old editions,” he recalls. “He had editions that were published before I was born. I read them all one after the other.”

He also read other comics that were published separately.

“For example, Zagor was my favorite,” he remembers. “I also read Captain Miki, Comandante Mark, Mister No, Modesty Blaise, Mandrake, and a few Western comics.”

His sister went on to fall in love with their neighbor and friend, which inadvertently contributed to Ismaili’s passion for comics.

“He had a collection of 2,000 comics, which he kept in four huge packages,” he recalls. “When he started dating my sister, he gave them all to me. I kept them in the basement.”

Then, in 1991, Ismaili was forced to leave Kosovo. He went to England and didn’t read as many comics as before. “It was a period when technology — with internet and Playstation — killed comics. Then the entire comic book culture disappeared,” he says, adding that even Serbo-Croatian comics were no longer sold in Kosovo.

Ismaili is a designer. Drawing was always a passion of his.

“But I never saw comics as something that I wanted to practice myself,” he says. “Perhaps I would be a good comic book writer. I was never a good drawer, even though I am a designer — but I was a good writer.”

In fact, comics were the reason for his return from England.

“Together with Shkumbin Brestovci, we established Rrota Publishing House and bought the rights for Marvel Comics,” he says. “We bought the rights to publish Spiderman, X-Men and Alan Ford in Albanian. Also, we bought the rights for Martin Mystère from an Italian publisher, although we didn’t manage to publish any editions of this comic.”

He adds that in 2003-04, they published seven editions: two editions of Alan Ford, two of X-Men and three of Spiderman.

But the job wasn’t easy.

“We didn’t do the market research properly,” he admits. “We simply did it because of our love, from the heart. In fact, I got a tattoo of the Spiderman logo when I came back to Kosovo!”

They published the Marvel comics as 32-page colored publications, Ismaili recalls: “We also bought the artwork, so it cost a lot. It cost us 500 euros to buy one edition.”

Ismaili explains that they would print 4,000 copies and sell them for two euros each.

This meant that they had to sell 2,000 copies to cover their expenses. The distribution was covered by Rilindja, but due to the lack of interest, as well as to unsuitable placement and damages in the kiosks, they did not manage to sell enough to break even, he says.

But this wasn’t Ismaili’s last attempt at comic book production. In fact, later on, he produced a different form of comics. Ismaili’s graphic series “The Pimpsons” became well known.

I received information from trusted sources about affairs, scandals, crimes etc. And when I felt like there was public interest, I published.

Fisnik Ismaili

“In 2011, after I entered the world of politics, we would attack the government, corruption, etc.,” Ismaili says. “I was inspired on the day when Atifete Jahjaga was elected as President. Watching the news on TV, I saw a set-up which to me seemed extremely absurd.”

He recalls how Christopher Dell, the U.S. Ambassador at the time, “took Atifete out of an envelope.” Leading political figures Hashim Thaçi, Isa Mustafa and Behgjet Pacolli were all present at the time.

“He got them all together,” he says. “That image got stuck in my head. Dell looked like a Simpsons character. And there were always jokes about how Mr Burns from The Simpsons looked like Isa Mustafa.”

It was in this way that The Pimpsons was born — he went home and drew Mustafa and Dell.

“Then I found an episodic personage who looked like Schwarzenegger,” he recalls. “A buff dude. I found him in uniform. He looked like Hashim Thaçi.”

He then found many Simpsons characters who looked like Kosovar politicians.

“I drew some of them myself — like Albin Kurti, for example,” he recalls, adding that he posted the first episode as a joke. “It was well-received. The people liked it. They wanted the second episode.”

“The Pimpsons” blew up in popularity after the first episode.

“And so there was the second, third, fourth… Every day I would publish one that stung more than the last,” he says. “Later on, I received information from trusted sources about affairs, scandals, crimes etc. And when I felt like there was public interest, I published.”

Ismaili’s comic’s grew in reputation and he would end up speaking about them in an interview with Al Jazeera. Moreover, he recalls how “MPR [Minnesota Public Radio] said — and I paraphrase — that this is the drawn version of John Stewart’s ‘The Daily Show.’”

“It lasted for a year, more or less,” he recalls. “It became very popular. We got about 20,000 likes on Facebook. 20,000 likes are a lot, even today, let alone in 2010.”

He explains that he later attempted to revive the project, but due to a lack of time to dedicate to it, and because it brought no profit, it failed.

“We tried to revive Banality, which was also a comic, which we drew with Vigan Kada, an illustrator,” he explains. “We thought about selling it as well. We opened a Facebook page and included a flash game in which you could generate your own comics. But it didn’t become popular, and it took a lot of time and resources.”

The historical subject

In addition to magazines, annexes and newspaper sections, comics also began to be published as books. In 2003, Rrota (Wheel) Publishing House published a few editions of comic books and in 2006-07, Rrokullia Publishing House collaborated with Express newspaper to publish a series of 10 biographical, historical, sociological and philosophical books as graphic novels in the Gegë dialect.

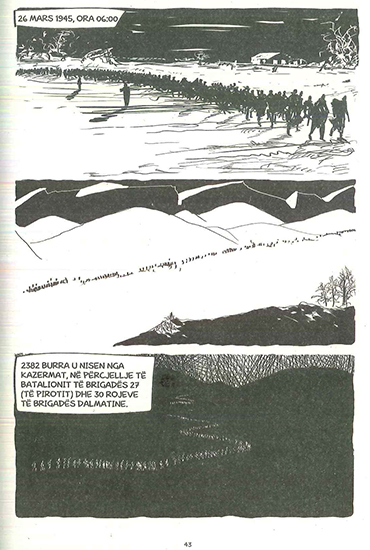

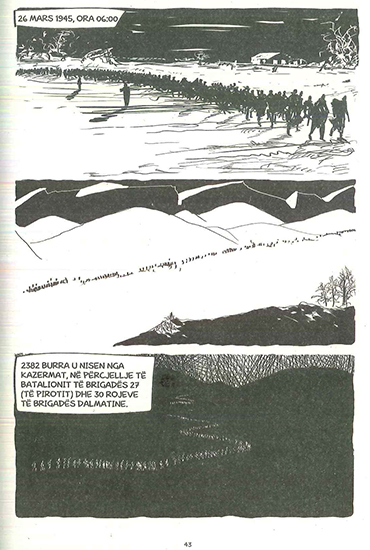

In March 2019, a graphic novel titled “Dimri i gjatë i vitit 1945: Tivari” (The long winter of 1945: Tivar) was published. It was written by Anna Di Lellio and illustrated by Dardan Luta, and is based on the Tivar Massacre of 1945, in which hundreds of Kosovar partisans were killed by their Yugoslav superiors.

Luta is of the opinion that public interest is quite high. “There has been a lot of attention from local media: not because it was the first graphic novel in this format, but also due to its subject, which has been silenced for a long time,” he says.

He explains that his work as an illustrator on this graphic novel started with an idea that Di Lellio came up with a couple of years ago.

“Her initial concept included many events of that time, and one of them was the violent recruitment of Albanians and their journey through the mountains of Albania to Tivar, where the massacre happened,” says Luta, highlighting that after a period of research, they decided to dedicate the whole story to this event, rather than to mention it superficially, as people had done in the past. “Today we have a story and a visual version that is also available to other interested age groups.”

Excerpt from Anna Di Lellio & Dardan Luta’s “Dimri i gjatë i vitit 1945: Tivari.”

Speaking about the difference between visual and literary narration, he says that there are readers who prefer the narrative because it allows their imagination to picture the recital, whereas “there are others who prefer comics because it highlights emotions of characters, the environment, costumes, etc. So it serves the tale as it is, leaving no space for other doubts, except the ones that the author decides to present.”

Luta is optimistic about the prospects of this genre.

“Graphic novels have a good future,” he insists. “They have recently revived. I hope that we will follow this trend, considering that we have many things to say and many stories to tell.”

He adds that future generations will have a clearer picture of the past, because they can interpret it visually, as is the case with comics.

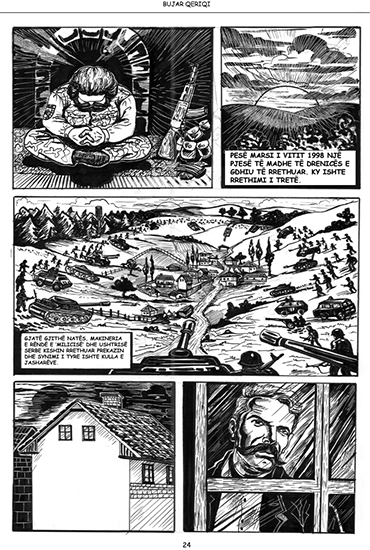

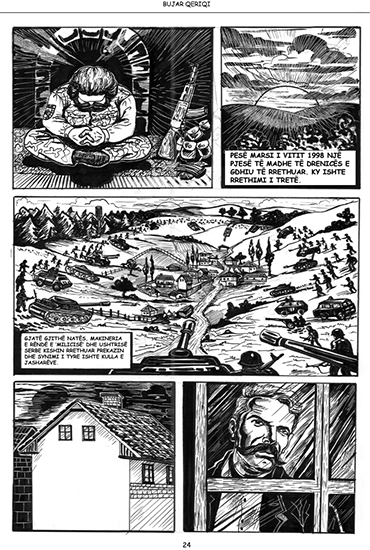

Around the same time as “Tivari,” a different historical graphic novel was published. But the subject of this one was contemporary Kosovar history, specifically the battle of Adem Jashari and his family against Serbian police in March 1998.

Bujar Qeriqi, author of graphic novel “Legjenda” (Legend), says that younger generations are interested in learning about Kosovo’s modern history not only through reading, but also visually. Seeing that there was no film about Adem Jashari’s story, he saw it necessary to create a graphic novel.

He also claims that it is the first of its kind in Kosovo. “‘Legjenda’ is mainly for students, but also for adults,” he says.

Excerpt from Bujar Qeriqi’s “Legjenda.”

Qeriqi says that he does not believe that the public was interested in his book due to the genre, but rather that interest grew due to the subject. “There is a lack of tradition for these kinds of books, and surely being a pioneer of the field is difficult,” he says.

He highlights the difficulty of writing pieces in this genre as the reason for the low number of authors of comics and graphic novels.

“Being a comic book author is not easy,” he says. “Comics have many details that must be put together, and the most important thing is for the comic to be unique and original.”

Interest in the genre

The largest bookshop in Prishtina, Dukagjini, states that public interest in comics and manga is quite high, and that the genre is read by people of different ages.

“There is demand for anime and Marvel comic books, which are for 10-year-olds,” an employee says. “But there are also many adults who read them.”

Employees of the bookshop say that since they have only recently begun to sell many different kinds of Albanian comics, readers are still getting to know the authors and their writing styles.

Edon Zeneli from the Buzuku book shop says that they began to sell actual comic books more than half a decade ago — especially Japanese comics, manga.

“To our surprise, there is a community of over a thousand youths in Kosovo who are interested in this category of books,” he says. “If we express it as a percentage, about 5% of our sales are comprised of these kinds of books. We believe that sales and interest will grow.”

He adds that sales especially increased due to the fact that the Marvel comics were made into films during the last decade.

“In France, for example, these kinds of books comes right after literature,” he says, referring to popularity. “In the U.S., it is a billion dollar industry. Here, understandably, it is in its first steps.”

Zeneli explains that interest in these kinds of books is still relatively low, and that the ones that are sought after are mainly in English. He believes that this is because there is little tradition of publishing these kinds of books in Albanian.

“And also Albanian authors are not quite as sought after compared to foreign authors, so it is understandable that they are not sold as much,” he explains, adding that in order to sell more of these books, they need to organize promotional events, book fairs and exhibitions at cultural events such as DokuFest.

Zeneli highlights the importance of the genre.

“One of the books I love the most, ‘Persepolis,’ is a book that achieved great success in the international market and was written in comic book form,” he says. “I want to highlight the importance of these books in the reading culture among youth and the development of intelligence in children that read them.”

Feature image: Agim Qena, “Tafë Kusuri.”

Dear Fitim, I own a Spider-Man comic Marvel Ultimate RROTA No. 1 ...bought in Kosovo 2002 ...the condition is mint...unread... would it be possible to tell me something about the collector's price? Thank you in advance + best regards: Daryl