The emerging illiterate class is hooked on Facebook videos – and that's good news for demagogues

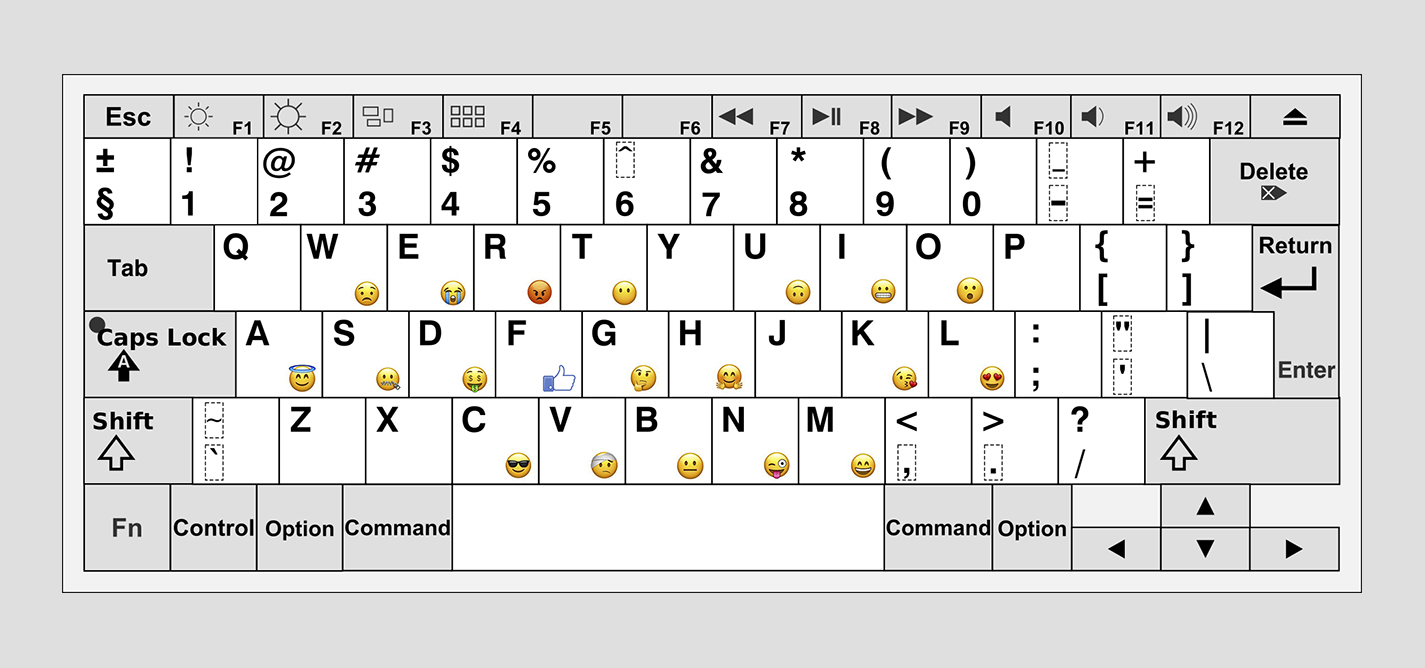

Millennials communicate through emojis, bringing forth a new form of over-simplified, emotional news.

|21.12.2016

|

Facebook and Instagram had killed hyperlinks to maximize profits by keeping users inside, and exposing them to more and more advertising.

It is clear that for a healthy, representative democracy we need more text than videos, at least to resist self-serving demagogues.

Hossein Derakhshan

Hossein Derakhshan is a Canadian-Iranian author and media analyst. He was the pioneer of blogging in Iran which earned him the title of ‘blogfather’ there. He spent six years in prison in Iran over his writings and web activism.

DISCLAIMERThe views of the writer do not necessarily reflect the views of Kosovo 2.0.

This story was originally written in English.