As NATO airplanes entered the skies above Kosovo on March 24, 1999, an entire spectrum of emotions was felt by those on the ground, down below.

There was cause for rejoice and optimism at last, after years of repression, struggle and being forced to live in the margins of society. But there was also uncertainty and trepidation, a fear that the intervention could see an intensification of the persecution by Slobodan Milošević’s Serbian regime.

As events panned out, all of the hopes and fears of that first night of uncertainty would come to bear.

During the 78 days of bombing, Kosovar Albanian civilians would become victims of grave atrocities — mass expulsions, executions and massacres. In the midst of the horror that was unfolding around them, more than 850,000 sought refuge in neighboring countries in a matter of weeks, fleeing any way they could — joining others who had already left in various small groups since the beginning of the war in March 1998.

Kosovo was being emptied through every possible gate, to Albania, Macedonia and Montenegro. In the first two weeks of the bombing alone, half a million people are reported to have arrived in Kosovo’s neighboring areas — forced into refugee camps, the houses of relatives or random strangers or seeking temporary shelter wherever they could find. Most could scarcely imagine that they would ever return.

But on June 9, the signing of the Kumanovo Agreement between NATO and the Federal Republic of Yugoslavia ultimately brought the war — and the exile of almost a million people — to an end.

Twenty years later, many who were forced to flee their homes prefer not to go back into the agonising memories of those days, as the feelings of fear and despair are still too raw.

These are the stories of three people who were forced from their homes, but who ultimately returned.

Escaping through the mountains

Angjelina Krasniqi was struggling with the tether of one of the two horses on which her parents were traveling across the harsh mountainous terrain.

She had been lucky enough to find the animals, which were provided by local villagers, who made sure that people who were unable to cross the mountains by foot still had a way to pass; it was a difficult six hour trip from Radavc, a village in the mountains north of Peja, up to Rozhaje over the border in neighboring Montenegro. The other horse was pulled by her friend’s brother.

Their trip was physically very hard work, but it was made even more difficult by the thoughts about their homes and lives that they were being forced to leave behind; as they left Kosovo they had the deep conviction that they would never again return.

“I can remember very clearly that I didn’t know how to hold the horse’s [reigns] or how to pull it,” explains Angjelina in her house in the Dardania neighborhood in Peja, the same house from which she left to seek refuge two decades ago. “My friend’s brother, who was accompanying us, said to me: ‘The horse is pulling you, rather than the other way around!’”

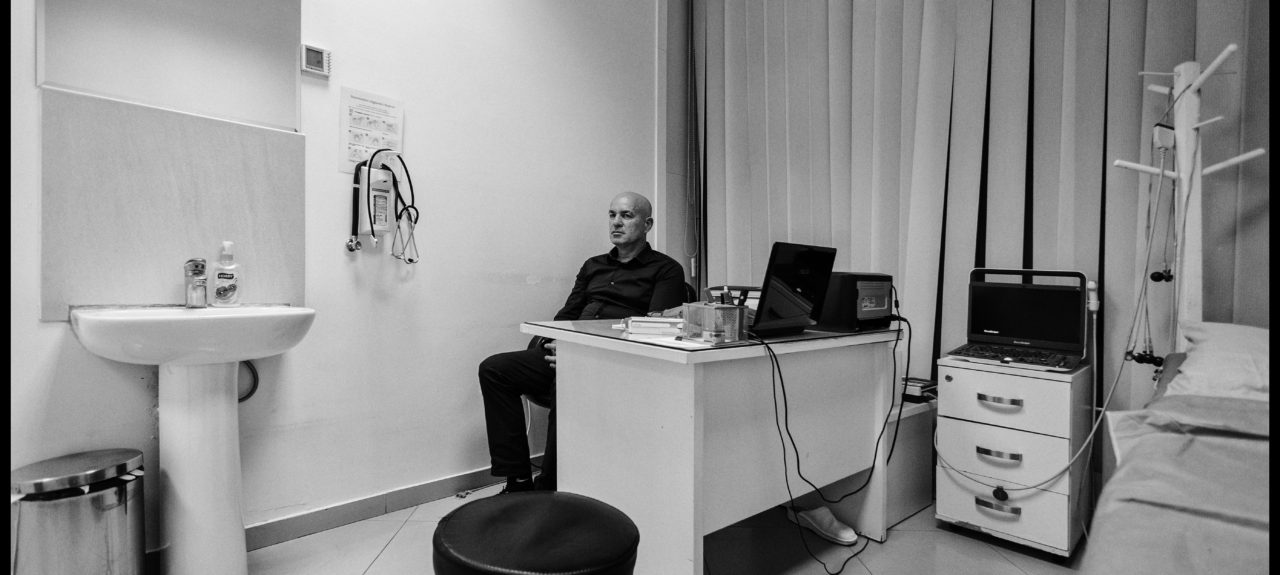

Angjelina Krasniqi became a target for the Serbian police because of her political activity. Photo: Ferdi Limani / K2.0.

Her activism in demonstrations in Peja and other parts of Kosovo from 1989 onward had turned Angjelina, who was in her early 20s at the time, into a permanent target of the Serbian police. She recalls that in the early ’90s, the political and social tension had intensified, as had the level of repression from Serbian forces.

“For a long time, around 7 months, I didn’t dare to leave my house. I stayed isolated inside, with no contact with people, the city, the outside environment, because it was highly likely that I would get imprisoned,” she says.

By the end of the decade, with the rise of the Kosovo Liberation Army (KLA), Angjelina and her activist friends started to take aid, mainly in the form of food, to villages situated deep in Drenica, the region in central Kosovo that had started to engage in direct warfare against Serbian forces.

Serbian police controlled every inch of the main magistral roads that connected Peja to both Mitrovica and Prishtina, forcing them to take the secondary roads through the rural areas — a journey of 9 hours.

But delivering aid wasn’t the most difficult job compared to what was to come.

“I remember that it was the Night of Eid when Dr. Liri Loshi took us to a family whose daughter had been injured in the fighting,” Angjelina recalls. “We put her in a box in the truck and took her back with us, again through the villages and to Peja, where she received medical treatment.”

"A neighbor of mine told me to leave as fast as I could because it was dangerous,” she recalls. “I asked my parents ‘Should we leave the house?’ and they said no."

When the war reached Peja after the battle of Loxhë in July 1998, the situation became even more acute. Angjelina says some of her Serb neighbors mobilized with arms and set up checkpoints in the streets, showing no compassion for the people who they had grown up alongside for years, or their children.

With the situation unbearably tense, she recalls the moments when she spoke to her parents about leaving their home.

“A neighbor of mine told me to leave as fast as I could because it was dangerous,” she recalls. “I asked my parents ‘Should we leave the house?’ and they said no.”

As they were discussing this, Angjelina told her parents that she was going to church, to the astonishment of her mother, because their daughter rarely attended. On the way there, she saw police heading to her house to look for her. Not finding her, they took her parents away instead.

With her parents arrested and imprisoned, Angjelina sought refuge for a few days in her friends’ houses, first in Peja and then in the village of Radavc.

She says she never liked guns, but throughout this time she kept a gun with her. “At least to have a bullet for myself,” she remembers thinking at the time.

"My mother was bloodied just about all over her body from the beatings."

Before long she decided to cross the Montenegro border through the mountains by foot to Rozhaje, a small town around 20 kilometers from the border with Kosovo. But racked with guilt that her parents were imprisoned and she was free, she decided to return to Kosovo and turn herself in so that her parents could be released.

When she got back, she found out that her parents had already been released, but they were suffering from serious health conditions, with both having been heavily beaten by the police.

“My mother was bloodied just about all over her body from the beatings,” Angjelina says.

Unable to return home as she was still a target for the police, they temporarily sought refuge in Peja’s catholic church.

Angjelina recalls having the impression that people were exhausted by the resistance, and there was little hope for an international response, especially due to events a few years previously in Bosnia and Herzegovina, where the international community only belatedly intervened having failed to prevent widespread war crimes including the genocide in Srebrenica.

It was in these circumstances that they took the decision to leave for Montenegro, a second departure from Kosovo that Angjelina describes as a “horrible memory,” only enhanced by the thought that the idea of ever returning home was just a dream.

She knew that her parents were in no condition to hike the harsh route through the mountains, and for a while she considered the possibility of carrying them. But when in Radavc she managed to get hold of the two horses to make the journey more manageable.

Even with the horses, the path was exhausting and they were completely alone in their travels through the mountains to Rozhaje during the last summer month of 1998.

When they eventually arrived, they took a private taxi to go to Ulqin. By this time, the journey had taken its toll — when they arrived in the Albanian-majority seaside town in southern Montenegro, all three received infusion therapy for five days.

Upon release from the medical facility, they settled in a rented apartment.

Throughout their ordeal, and with phone lines in Ulqin at a premium, Angjelina lost contact with her four brothers who lived abroad; her fifth brother, Pren Krasniqi, had stayed to fight in Kosovo.

Within weeks of arriving in Ulqin, and with the family still separated and communication lost, Angjelina received shattering news. Pren Krasniqi had been killed.

To this day, she struggles to think back to that moment as the pain she felt was so great.

“Those moments were so grievous that I rarely recall them because the pain was so severe,” she says. “You can imagine what it was like when my parents heard that their son had died, or when I was told that my brother had died.”

After digging around for more information and paying up to 100 marks for three minutes on a rare private phone, she found out that there had been a mistake — the Pren Krasniqi killed wasn’t her brother, but another person with the same name.

Ulqin was suffocated by the influx of people in those days, as the NATO bombing campaign precipitated an increase in atrocities by Serbian forces and the consequent flight of hundreds of thousands of people; due to the lack of capacity, people slept in public spaces, religious facilities and in the street, until they found more long term forms of shelter in private houses.

Angjelina was unable to sit and do nothing, so she became engaged in the emergency headquarters in Ulqin, providing aid to other refugees coming from Kosovo.

The beginning of the end of her ten-month stay in Ulqin came with the start of the NATO bombings. The missiles fired from ‘Aviano,’ the NATO air base in Italy, could be seen from Ulqin Castle flying overhead, and they were met with unrepressed joy in the form of tears and screams from the many people who gathered there to watch.

Refugees in Montenegro

Around 70,000 Kosovar Albanians fled to Montenegro during the war in Kosovo.

Montenegro was still part of the Federal Republic of Yugoslavia at the time and therefore, unlike Albania or Macedonia, it had no official refugee camps. Many refugees therefore stayed with family members or with random strangers, while others paid for rented accommodation or hotels.

Albanian-majority Ulqin in the far south of the country became the focal point for most Kosovar Albanian refugees.

Around half of the refugees in Montenegro made the journey through the mountains from Kosovo as an emergency means of escape, before subsequently crossing into Albania.

As soon as the war ended and the bombing ceased, Angjelina was determined to return home right away; she entered Kosovo through the Kulla border crossing point in her friend’s Yugo, driving right behind the NATO military convoy, while Serb residents were leaving Kosovo by car in the opposite lane. It’s a scene that is etched in her mind, and which she describes as “the last encounter of interhuman hatred.”

Entering Peja again for the first time, they found a city that had largely been burnt to the ground. The smell of smoke had become one with what remained of the city.

After settling in their friends’ apartments where it felt safer in the immediate aftermath of the war, she worked alongside other volunteers from the Nënë Tereza Association to immediately establish six food distribution points for those who quickly returned to the city where you could barely hear any breath of life.

Angjelina recalls an event she says she’ll never forget. A woman with her 7- or 8-year-old daughter came to the food distribution point. They had been locked away for two weeks in the basement of their house, unaware that the war had ended; eventually, they were forced to leave the basement through hunger.

“I remember when the little girl came, she ate a whole loaf of bread within four or five minutes,” she says. “Her mother insisted that they take 20 loaves of bread, because they had been without food for so long.”

‘You’re never coming back here again’

In March 1999, a few days after NATO had begun its bombing campaign, Hamit Krasniqi had gone with his family to his birthplace in the village of Kijevë to celebrate Bajram.

This time, when the 45-year-old primary school teacher returned to his house in the Arbanë neighborhood on the edge of Prizren with his wife and three children, something was different. Near their house by the main road, they met some neighbors who told them that virtually the whole neighborhood had been expelled on Bajram by Serbian forces.

Hamit Krasniqi left Prizren to go to Albania by bus together with his wife and their three children. Photo: Ferdi Limani / K2.0.

“Fortunately or unfortunately, we weren’t at home,” he recalls, sitting in the garden of the same house that he still lives in to this day. “When I came here, I [hardly] found any of my neighbors. For about a month, we lived here with two or three neighbors.”

In the weeks that followed, the high concentration of police in local neighborhoods and along the main roads made life dangerous. Hamit took the decision to take his family with him to a friend’s house in the inner city area, which many perceived to be safer due to the higher concentration of Albanians living there.

“From the end of the bridge in Prizren to Morina, I saw horror."

They stayed for about three weeks, but with the atrocities committed by Serbian forces having intensified since the NATO bombings began, and Kosovar Albanians who resisted the expulsion campaign being especially at risk, Hamit decided it was too dangerous to stay any longer.

Even though by this point the circumstances made the idea of leaving Kosovo seem inevitable, the practicalities of doing so were not straightforward.

“I’d injured my foot and couldn’t walk,” he says. “I didn’t have a car, although it was dangerous to drive.”

Hamit decided to contact a man from Mamushë village to the north of Prizren who he knew drove a bus between Prizren bus station and the border crossing with Albania at Morinë.

“The friend of a friend said to me: ‘Hamit, if you want, we can take you to the border,’” he recalls.

Hamit and his wife took their two daughters, who were aged 13 and 10, and their 5-year-old son to set off on the desperate trip that they’ll never forget. Their relatives, Hamit’s brothers, had already left from Kijevë to Ulqin.

For Hamit, the road from Prizren to Morinë, which lasted no more than an hour and a half, felt like 10 hours.

“From the end of the bridge in Prizren to Morina, I saw horror,” he says. “I don’t know how to describe it. If I were to explain it to my children tomorrow, they would not believe the terror that was inflicted.”

From the windows of the packed bus, the passengers witnessed terrible scenes throughout the whole trip. Hamit says he saw people fleeing any way they could, with small and large tractors carrying stoves on the back and the Serbian police beating the expelled and taking the few things that those people had left: money, rings or anything valuable.

A number of times along the way, the police stopped the bus at checkpoints. He particularly remembers one incident a few hundred meters before the village of Zhur, when paramilitaries “with balaclavas” entered the bus.

“The girls were terrified,” he recalls, adding that they couldn’t sleep properly for a week after the trip. “I told them not to worry because they would not harass us.”

In the last kilometer before reaching the border crossing with Albania, a policeman that Hamit knew from his neighborhood in Prizren once again conveyed the message that police had learned by heart and that they would recite eagerly: “Go on, get out of here, because you’re never coming back here again!”

To those on the bus seeking safety in Albania, it was hard to believe that the words were anything but the truth.

When they arrived in Kukës, Hamit says he saw so many refugees that he thought the whole of Kosovo was there.

Refugees in Albania

During the war in Kosovo, Albania took in around half of all those fleeing Kosovo. In total it is estimated that almost half a million refugees from Kosovo headed to Albania.

By May 1999, around 100,000 refugees were staying in Kukës, a town 15 kilometers from the Kosovo border. But Kukës was a remote town and lacked the capacity to accommodate the thousands of refugees arriving each day and the city was also subject to occasional shelling by Serbian forces. So the government of Albania, in cooperation with international organizations, tried to move some of the refugees to southern municipalities by bus.

In total, Albania had 49 official refugee camps during this period, many of them tented but others in public buildings. As in other countries, the local people also opened up their houses to people fleeing Kosovo, with Albania thought to have had around 129,000 host families.

But with basic living conditions lacking, in the morning after a sleepless night, they took a taxi to Tirana. “Usually when you are in hardship, Albanians double the price,” Hamiti says with rancor, suggesting that they paid 400 marks for the trip.

Getting into Tirana that day proved impossible though, with Hamiti describing the entrance of the capital as being blocked by the high flux of refugees arriving from Kosovo. They decided to change course again, heading initially to Durrës before deciding to continue 20 kilometers further south to the coastal village of Qerret.

Hamit doesn’t remember exactly how long they stayed there, but recalls constantly thinking of Kosovo; their only contact with home was through watching TV reports or reading newspapers.

“Initially we thought we would never return, but when NATO started really bombing [more intensively], then we got our hopes up a bit,” he says.

Then, in early June, news came through of Kosovo’s liberation — an event that had seemed so unimaginable just a few short months earlier.

Hamit recalls the news being celebrated with such emotion that it sounded like the roars heard in football stadiums in England or Spain when fans celebrate an important goal.

“I think all of Durrës screamed,” he says. “We got the good news that we were going back!”

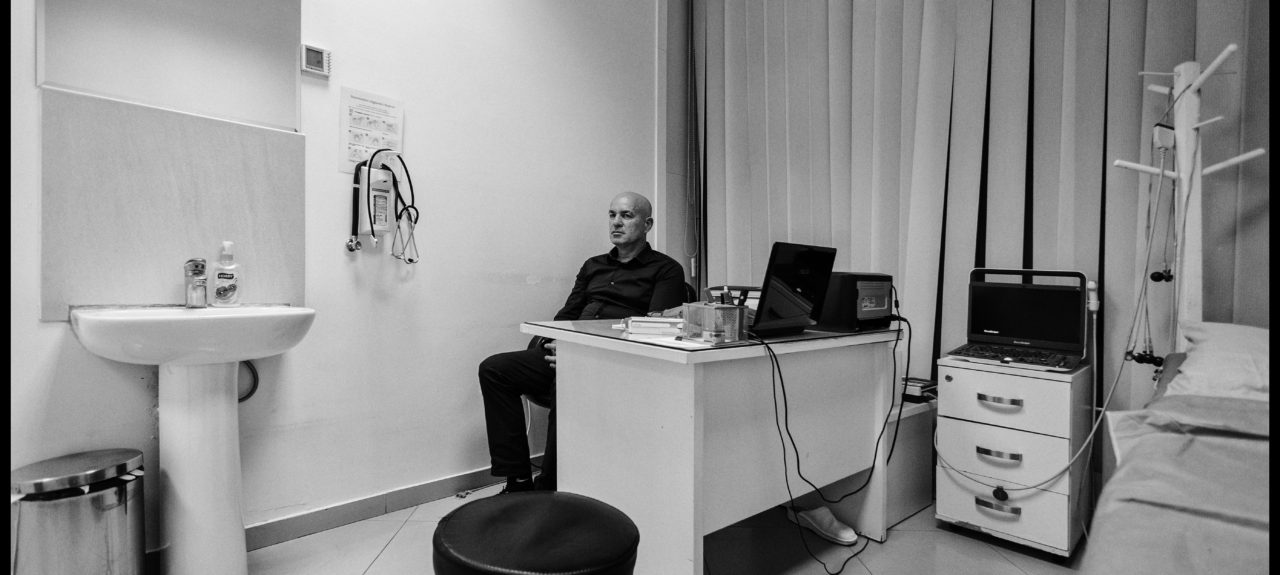

Urim Cerkini was one of the first to return to Kosovo after the war, as a medical translator for the American army. Photo: Ferdi Limani / K2.0.

Expelled, but with no way out

Urim Çerkini was a third year student in the Faculty of Medicine at the University of Prishtina in 1990, when he went to enroll for the sixth semester. But unlike previous times he’d enrolled, the clerks weren’t behind their desks — the government had closed the faculty.

In fact, it had also closed all the other faculties at the university, as part of a systematic move to dismiss Albanian public sector workers, from schools and hospitals to factories and the media.

The memory is a difficult one for Urim, as it signalled the hard times that were to come.

He continued his studies in Prishtina, but like other students, he was forced to do so in clandestine conditions in private houses as part of the parallel education system.

Needing to travel every day from his hometown in Ferizaj to Prishtina, the level of risk was high, especially for a student. Police would carry out regular checks on busses and trains, observing, arresting and questioning passengers who they suspected of being involved in actions against the regime.

He was arrested a number of times by the Serbian police in Prishtina, but he kept this secret from his family to spare them the inevitable concern; his parents had already had to deal with the stress of his older sister being arrested more than a decade earlier in 1979, and with his younger sister being arrested, beaten and tortured in 1981.

By 1998, Urim had completed his exams and was waiting to graduate. On March 5, he recalls being at a friend’s party in Prishtina, when the joyful atmosphere was interrupted by news coming through of the massacre of the Jashari family in Prekaz.

The massacre was a moment that would accelerate the course of events to come.

"We started to celebrate, thinking that it was the NATO planes bombing the barracks, but in the morning we were horrified to find out the truth."

About a year later, the situation in Kosovo had intensified. In Ferizaj, Serbian police were stationed in the building that is now Ahmet Hoxha school, barely 100 meters down the road from Urim’s house; the neighborhood was completely isolated, with Serbian forces using snipers to control the movement of residents in their backyards.

International monitoring staff had settled in another building across the street from the school. Urim presumes this made the house a target — one day, when the house was empty, Serbian forces mined it and blew it up.

Urim and his family heard the blast very clearly.

“We were at our cousin’s house when we heard a loud blast,” he recalls. “Initially, we started to celebrate, thinking that it was the NATO planes bombing the barracks, but in the morning we were horrified to find out the truth.”

The house had been completely demolished, and there had been heavy gunfire during the night.

After the events of the night, it became very hard for the Çerkini family to stay in their home. But the decision to leave was still a difficult one to make. Urim recalls that it was his mother who insisted that they leave, despite opposition from him and his younger brother.

Ultimately, on April 1, 1999, Urim, his mother and his brother left from one house, and his brother’s family, which had six children, left from their house next door to go to the train station in Ferizaj.

When they arrived, however, the hoards of people streaming into the station and the trains arriving already overflowing, made evacuation impossible. Having made the agonising decision to leave their home, it felt like another cruel blow that they were unable to escape from Ferizaj that day.

The heavy police presence made returning to their homes impossible, so caught in limbo between expulsion and their inability to escape, they were forced to spend the night at a relative’s house in another neighborhood, together with dozens of other people who hadn’t managed to get out.

The next day, on April 2, they all took a bus to Hani i Elezit and on to the border with Macedonia.

But this was not the end of their ordeal.

Seeking international aid to help cope with the sudden influx of people, Macedonia had taken the decision to close its border with Kosovo. As a result, thousands of people who were being forced to seek refuge were left stranded in the no-man’s-land area known as the Field of Bllacë. This cold and muddy field would become ingrained in the collective memory of Kosovar refugees.

Refugees in Macedonia

The Field of Bllacë, a no-man’s-land area on the Macedonian border, where 65,000 refugees faced appalling conditions for days before being allowed to cross into Macedonia, became synonymous with Kosovars' exodus from war.

During the war in Kosovo, around 360,000 refugees sought shelter in North Macedonia. Many of these were in eight camps, all in the Skopje and Tetova areas. At their peak in May 1999, these camps sheltered more than 110,000 people, with the largest hosting more than 20,000 refugees each.

As in neighboring Albania, the majority of refugees were hosted in private family homes by people who opened up their doors to provide shelter for those in need.

Urim recalls that it was raining, there was no food and the conditions were unsanitary. Children would not stop crying. Left under the open skies, they all waited to be allowed to cross the border.

Around 48 hours after Urim and his family arrived in Bllacë, the border was opened and refugees were allowed to cross. Two of his cousins in Skopje ensured they were swiftly evacuated from Bllacë in a truck, which Urim clearly remembers was also carrying a coffin.

They stayed for around six weeks with relatives in the Çair neighborhood of Skopje in a house that Urim says became a meeting point for Albanian refugees. But with space at a premium and pressure from authorities for refugees to be registered in official camps, they decided to move to the main refugee camp in Stenkovec, half way between the capital and the border with Kosovo.

Having studied medicine and knowing English, Urim quickly found work with Doctors of the World, an organization that was engaged in the camp alongside many other international missions and organizations.

On June 9, a few weeks after Urim had arrived at Stenkovec, an agreement was reached at nearby Kumanovo that brought an end to the war.

Urim was told by his brother that U.S. troops, which were by now stationed in Macedonia, were seeking a translator. He decided to apply and was ultimately hired as a medical translator at the as-yet unbuilt Camp Bondsteel near his hometown.

Working with the Americans meant that he was one of the first people to return to Ferizaj, entering via military helicopter just days after the war ended.

But frustrated with the constraints of being unable to move freely or contact his family, within a few weeks he decided to quit and head home to be with his mother, who he found out was home all alone.

He discovered his neighborhood almost completely abandoned. There was sadness all around, in the empty streets and among the people who had experienced all kinds of unimaginable things.

The biggest concern was for the fate of the people. A neighborhood resident had been executed on his doorstep; another killing had happened a few houses down.

Besides freedom, everything else was lacking. From that point, Urim says, life started from zero.

“I hope no one in the world, not even my enemy, experiences getting expelled from their country as a refugee like we were back then,” he says through tears. “It’s the worst feeling that one can experience.”K

Feature image: Ferdi Limani / K2.0.

Video: Trendelinë Halili / K2.0.