How’s life?

To kick off our ‘LIFE’ media carnival, K2.0 editors reflect on body, place and voice.

By Besa Luci

The majority of discussions we end up engaging in center around some aspect of “life.” Life’s qualities; life’s possibilities; life’s expectations; life’s difficulties; life’s uncertainties; life’s injustices; life’s alternatives.

At its essence, life is the one fundamental thing that people everywhere share, and struggle over. It is an obvious but important reminder of connectedness, and one that became particularly visible over the course of the past 18 months as the pandemic joined all in a global discussion over the grave toll COVID-19 had taken over people’s health and welfare.

Amidst recurring forms of quarantines and lockdowns affecting people’s mobility and livelihoods; the subsequent global economic fallout with the most dire impact on those already vulnerable and fragile; ongoing political turmoils or clampdowns by power elites seeking to profit from the crisis; and death often becoming a mere faceless statistic that barely begins to tell the tale of political failure and mismanagement — it has been life, that in one way or another, has been at the center of it all.

Yet, how we talk of the different facets of what constitutes life is telling of which experiences and what narratives are deemed to warrant merit and whose struggles end up being disregarded, ignored, or belittled.

It raises the question of worth, and one important venue where such deliberations occur is within the media itself. Life, though maybe not always mentioned as such, is continuously at the center of journalistic exploration. And those writing the stories of it end up making decisions that can affect what we know, see, read or understand of society around us.

Confronting LIFE

This is one of the reasons that at K2.0 we chose LIFE as the theme of the second edition of our annual Media Carnival.

Following a prolonged period when one of the most recurring questions seems to have been “when will life return to normal?” it seemed only fitting to question not only what constitutes life itself for different people and communities, but also to challenge the idea of a return to the way things were before. Because, the longing for a return to “normality” is something that has often been challenged or rejected, particularly when considering that “normality” does not equate with wellbeing for so many, and was not necessarily something to be upheld to begin with.

It has been said many times, but it requires repeating because it continues to hold true — the pandemic ended up exposing the vast structural and systematic inequalities both globally and more locally.

This is reflected on so many levels: the slow vaccine rollout to poorer countries, with the initial hoarding and vaccine nationalism by richer countries; the economic relief packages that favored conglomerates over small businesses, or owners over workers; the continued disregard toward migrants as “the other” not meritting attention, even in light of a global crisis that was supposed to have triggered some form of compassion; the apparent cultural acceptance that women continue to end up being killed at the hands of patriarchy; the political attempts to control and regulate the bodies of “others” when they are deemed “different”; the continuous disregard for how damage being caused to our common place, the environment, is sold off as a promising venture for employment, all on the back of individual profit and self-interest.

Different versions of such stories end up in the media. However, rarely with the sense of urgency or resoluteness they require. Rejecting a complete return to the pre-pandemic realities could become the framework through which a re-imagining of life is envisioned, and fought for.

Body, Place, Voice

Which leads us to “How’s Life?” — the question K2.0 is posing, with the aim of remembering, rebelling against and reimagining everything around us.

And we’re doing so by focusing on “Body, Place and Voice,” as three subjects where struggles for control, dominance and power particularly manifest themselves.

Body, which besides its commonly referred to biological existence, is socially and politically all too often treated as an object in need of regulation. Bodies are prescribed a sex, gender, race, ethnicity and other traits, and scorned when viewed through values others attach to them — in constant attempts to manage. Meanwhile, liberty over one’s own choice or self-identification needs to be continuously negotiated and fought for.

Place, a venue for exploring not only one’s sense of belonging, rejection or expulsion, but also how such sentiments are an intricate part of politically and economically driven projects to determine our existence: who has access to a place to call home, and at what cost? Who can participate in the making of a city, town or village, and to what extent? Who can engage in the fight against the destruction of the environment, as home, all around us, and how safely?

And ultimately, Voice, which comes down to recognizing, using and not compromising one’s agency, particularly when facing forces that seek to silence or delegitimize criticism. Because each story, experience or viewpoint that is non-conforming is a voice that warrants recognition.

In all three of these subjects, the media and the choices we make over what issues receive prominence, which experiences are recorded, and how we engage in depicting them and defining the contexts within which they are situated are crucial and require continuous self-scrutiny.

That is why, as part of our four-day media carnival, we have put together a program of exceptional and inspiring voices that will share their questioning, challenging and rethinking of how we talk about and experience body, place and voice.

In order to kick us off, the following section offers a collection of reflections and perspectives by some of us at K2.0, exploring personal encounters and confrontations with how questions over body, place and voice are intertwined in much of our daily lives.

A story of pain

By Aulonë Kadriu

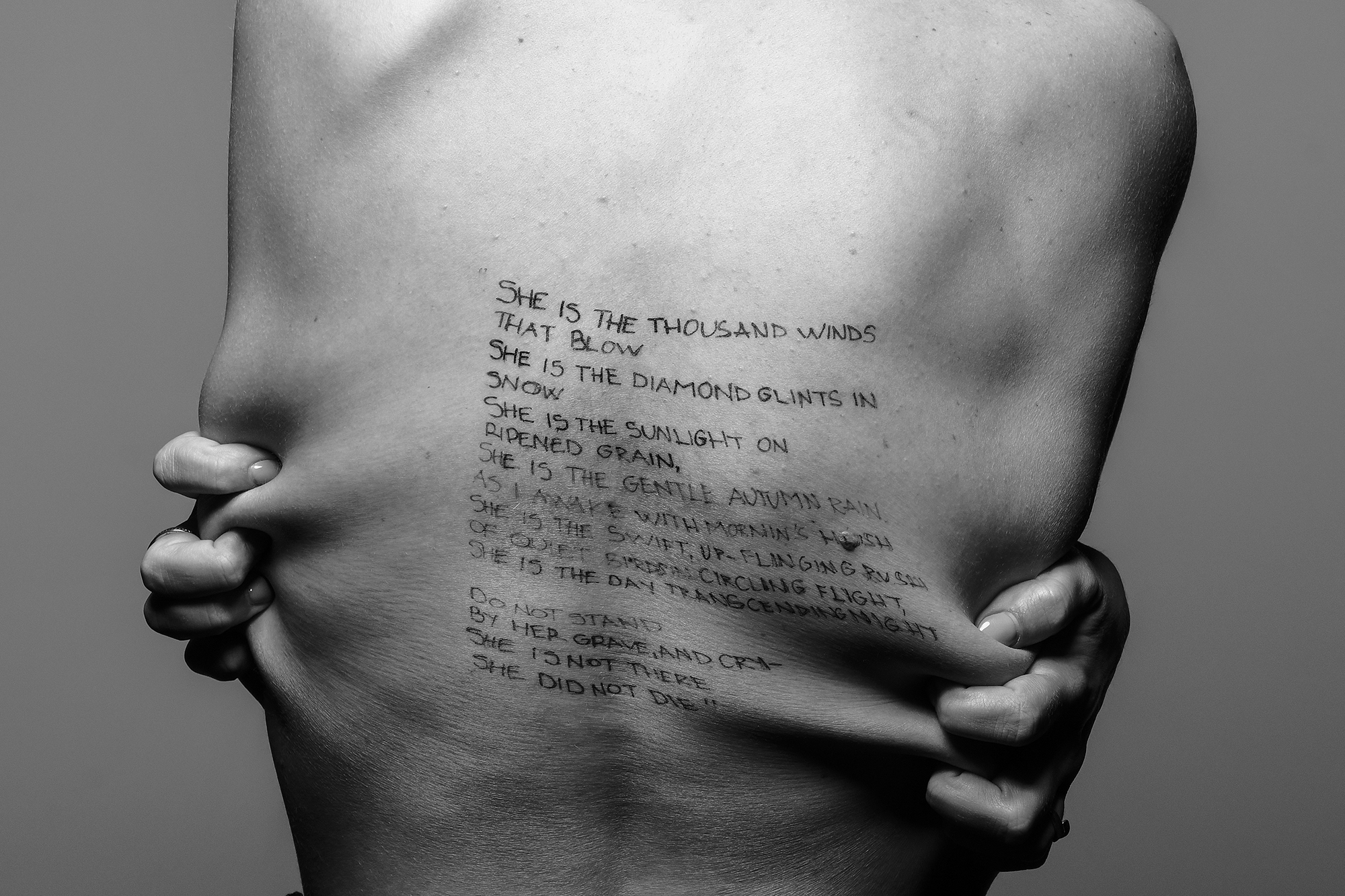

“She is the day transcending night”

Interrupted. Me and Her. And this is a story of pain.

“She is the thousand winds that blow

She is the diamond glints in snow

She is the sunlight on ripened grain,

She is the gentle, autumn rain.

As I awake with morning’s hush,

She is the swift, up-flinging rush

Of quiet birds in circling flight,

She is the day transcending night.

Do not stand

By her grave, and cry—

She is not there,

She did not die.”

She did not die. He killed her.

Adapted from Mary Elizabeth Frye’s “Do not stand at my grave and weep”

BODY GONE, BODY ALTERED

By Aulonë Kadriu

In a vain attempt to maintain my body, I went swimming that day. The very day she died. Pointless, I later realized. Pointless is the word to depict my frivolous fight to maintain, while she was fighting to survive. To maintain and to survive. To be and not to be. Me being and her not being. I chose to maintain; she never chose to fight to survive. Of all the battles one chooses to fight, I am sure as hell basic survival is not one.

While my body was overcoming the water, soaked in an illusion of freedom, she did not stand a chance. I was staying above the water, while a storm came her way. She was deprived of control. Paralyzed, she was being pulled under. Eventually, she sank.

He, the unendurable weight pulling her down. She, yet another martyr in an uncalled-for battle. He had already killed her. I just had no idea. Not just yet. Living in a thwarted pursuit of freedom, with brief glimpses of happiness, little did I know that the world was crumbling. Shattered into sharp pieces that hadn’t reached me just yet. The storm had arrived. Breathing in, breathing out, little did I know that she had been killed and I was alive and that this fact would become the very weight that lured me to the bottom.

I had to keep swimming. I had to choose to keep my head above the water. Choice was a luxury to her. I had to keep my head above the water so that, perhaps, one day choice will come cheaper.

My body quivered. Powerless. But I was alive. She was not. She was violated. Dead. In a box. Mine was in shock. He took her life and shifted mine, from miles and miles apart. She was gone. In a blink of an eye. In a gunshot. In a second. Here we were. Two bodies in orbit distorted by the whims of a man. One alive, one dead. Two bodies. One forced to die. One forced to live questioning her very existence.

When one has an out-of-body experience, the patterns of this world come into question. The body I try to preserve and secure, in a world that is so eager to own it, had shifted. Forever. Shifted, so as to not be held back by patterns anymore. My body will prevail. In a new world shaped by bodies like mine. Bodies like hers. Shaped by bodies that won’t be owned. For the bodies we lost.

Walking for a different life

By Nidzara Ahmetasevic

It took him five years and ten months to come from India to Spain, to see his brother. Most of that time, G. walked, except from India to Turkey.

When he got to Turkey he started north, walking toward Greece. It took him six days. Once in Greece, in the EU, he was hoping the journey was over, and he would have a chance to start a life, find work, get status… Nothing happened for two years. Then G. decided to continue toward Spain where his brother lives.

From Greece he walked to North Macedonia, then Serbia, and then, across the river, to Bosnia and Herzegovina where he got stuck until mid-June this year. During that time, 21 times he tried the game, a risky journey across the green borders to the EU.

While in the Balkans, he was pushed back by different police forces, mostly from the EU side, endlessly, stopped by walls, wires, police dogs, beaten so many times that it became normal. All that time, he was deprived of basic rights. Often also of food and water.

Finally, in mid-June, G. decided to try one last game. If he fails, he will go back to India. The game lasted 18 days and took him across three countries. And finally — standing on his own feet, but feeling like bear food because his shoes had fallen apart at some point— he reached Italy, and soon continued towards Spain.

The game is over for G., and now he has a chance to start a new life.

G. is one of many people who walked across the Balkans in order to reach a place where they will be safe and get a chance for a better life. Their feet are carrying the stories of a life in a world of closed borders, a world where we are not equal. It is a world where for some of us to just meet with a family member who lives in another country, we are required to go through a game in which our lives are tokens for somebody else to play with.

Since the Balkan route became a main migratory route toward northern and western Europe in 2015, everyday people are walking in their attempt to reach the European dream. They are coming from Afghanistan, Eritrea, Syria, Palestine, Nigeria, Congo, China, Turkey, Libya…

They walk across the fields, forests, mountains, rivers… Sometimes over 16 hours in a day.

Their feet become like open wounds.

At some stages of the journey, they meet people who help them, sometimes giving them new shoes, sometimes first aid, sometimes just a smile and a piece of food. Those who help often feel as helpless as those who are walking, both faced with the cruel policy of closed borders.

“It hurts,” are the words often repeated by people who are walking. It refers not only to the physical pain, but the pain that will stay inside of them for a very long time, a reminder of fortress Europe, which is often stronger than what their bodies can endure.

Their lives and freedoms are controlled by the privileged, those who can go wherever they want, who walk only if and when they like. They live in the borderless world, and believe they are the only ones who have a right to that kind of freedom. They ask for “humanitarian corridors,” they create refugee camps that look like detention centers, they collect old shoes and clothes and bring them to those who are deprived of life and basic freedoms.

“My legs hurt, but I know it will go away,” young Y. told me when we met in Sarajevo after he had been pushed back from the EU for the 5th time. He tried to enter the EU from Romania, but the police stopped him, and then tried to break his bones. After being pushed back, Serbian police continued the ugly task of sending the message that migrants and refugees are not welcome in the EU.

He will try again from Bosnia to Croatia.

“It hurts, sister, but I am tired. I need nothing. I just need to go. Just it,” he wrote to me in his broken English.

Their wounded feet are like images of a new Europe, the one we are living in today. Images of the nightmare which lasts for too long.

A PLACE SHE NEVER HAD, A PLACE I NEED TO FIND

I went home, a safe place she did not have. A safe place she didn’t get to at least die in. She was far away from both, from home and from not dying. She, like many other women, never got a taste of comfort anywhere. They live – if and when they get to live – displaced.

There might be better places to die, but there aren’t better places to be killed.

She was killed out of place. In an illegal place. From a living body, a hopeful voice, she became a murdered migrant woman in a heartbeat. Tables turned. A hopeless intersection. Once again displaced. Eternally and repeatedly executed. In a world that hastily chases the news, and that just as hastily forgets, she was no news. In a world eager for scandal, her death failed to even scandalize. In a world thirsty for tales of blood, hers was unwanted.

Not quite enough for the headlines there. Not quite enough for the headlines here. And I had to find a place in me, for her to rest peacefully. And a place in the world that did not spare a minute of tranquility for her. A place where she is a body, a voice.

She was no news. She became the frontpage of my life, its headlines, its definition.

It was meant to be. That might have been the case for every other death I have witnessed in my life. We learn to practice life; we even call it an art. But one can never practice death. While we cannot learn the unlearnable, what has never been shown to us, we learn to be prepared. To live our lives, knowing that death will be an occasional yet constant encounter. While you can never be well prepared for life, one is even less prepared for death. Yet people do everything humanly possible to ease the pain of permanent loss that comes with death.

But she was not meant to die. What happens when someone who has lived inhumanely is killed inhumanely. Those of us left in the killing’s wake, is there any way of coming out of it whole?

I say yes. Reluctantly so, but yes. But you have to come to terms with the interruption. Because murder is not like death. It disrupts. Interrupts. And you have to plug back into life.

You are never the same after someone you loved is killed. After someone you knew is killed. An acquaintance. Someone whose name you saw on your phone contacts list, even. Someone who sent you an email, even once. It becomes impossible to speak about life without the conversation slipping to death, the one process you cannot undergo twice. You cannot have a bad death once, and plan a better one later. The one irreversible process.

I too, foolishly believing I had mastered the art of life, thinking life was an art to begin with, always thought that loss has a pattern. Pain. Grief. Healing. Pulling yourself together. Living. And I thought death was out there. Not here. This is the first shock. Her killing changed all the patterns of death. If death ever seemed linear, yours had an insane amplitude. Waves. Curves. Restless movement. Up and down. Up and down. Her death alienated me from my own language. My bodily reactions. My habits. I have not faced it on my own terms. She did not die on her own terms.

She died on a man’s terms. He chose the course of life for her. For me.

Language rejects her death. Death and her name cannot be in one sentence. Which is why she is anonymous today. She is anonymous because she is not the only one. She is anonymous because there are so many names. She is anonymous because she is so present. She did not die. She was killed.

From one home to another(’s)

By Jack Butcher

My decision to leave Prishtina had caught me somewhat by surprise.

Forced into a choice between being indefinitely locked down alone in the city that had captured my heart five years earlier and heading for a faraway village from a former and increasingly distant life, it hadn’t been my first instinct.

I’d had no thoughts of leaving as Kosovo’s first cases of COVID-19 were announced on that Friday 13 as I sat with colleagues working late in the office to get the story out. And I still hadn’t considered it the next day as we trawled through the swathe of imposing new restrictions brought in overnight that limited almost every area of citizens’ lives.

But after some frantic — and rather emotional — phone calls with family members back in the UK after they’d got wind of the lockdown and imminent border closure, I found the tug of my roots to be overwhelming during a moment of such global uncertainty.

With hours to go until the borders slammed shut and with airlines rapidly cancelling flights, I desperately threw what I could of my life into a backpack and, in the dead of night, headed to the airport. A few hours later, still in shock, I huddled into a plane seat on the last flight out of Kosovo and watched the bright lights of my adopted home disappear beneath me — unsure when I would be able to return.

And so here I was, amongst the rolling foothills of a remote and rugged National Park, in the quaint English hamlet that I had grown up in but that I hadn’t called home for over a decade. The familiar sounds of tallava or hip-hop leaking unabashed from the built-up traffic was replaced by the occasional hum of a neighbour’s lawnmower somewhere down the valley; the rhythm of the call to prayer in the old part of the city replaced by the chatter of songbirds seeking food for their young.

I spent much of that spring in denial, telling few people of my knee-jerk decision to desert; the less people who knew, the easier it was to will myself back into my abandoned home. So as if to assuage my guilt at having left at the first sign of crisis, I threw myself into every aspect of lockdown life back in Prishtina, from closely scrutinizing the latest pandemic-related restrictions to hosting online parties for my friends.

Part of that also meant diving even deeper than ever into my work as an editor at K2.0.

Now, as my colleagues and I scrabbled to make sense of what the overnight upheaval meant for workers, single mothers and individuals already struggling with their mental health, we also found ourselves covering a simultaneous political crisis. With citizens trapped in their apartments and impotent to act, shady dealings by local actors coupled with the last flings of desperation from the Trump administration in the U.S. unceremoniously brought down Kosovo’s newly elected “Government of Hope.”

The anger, incredulity and deep sense of injustice I shared with my friends and colleagues in Kosovo was hard to reconcile with the sedate and tranquil world I was physically inhabiting. In my room, in video calls, I talked of government collapse and constitutional coups, while outside my window primrose bulbs or the closure of the local café were discussed over freshly baked brownies.

There may have been the occasional chatter about PM Boris Johnson’s health or another dodgy emergency contract issued to a mate of a minister, and the ever-present post-Brexit fallout inevitably hovered somewhere beneath the surface. But for the most part I blanked out this noise, considering it small fry compared to the far more pressing issues back home in Kosovo.

I insisted that my friends in Prishtina take me out — via their phones — onto their balconies each evening to join the nightly protests as citizens bashed pots, pans or anything they could get their hands on to register their opposition to the underhand wrestling of power. Meanwhile, once a week, I would step outside onto the front drive alongside all the neighbours to politely clap for the UK’s beleaguered health workers as the number of cases, deaths and hospitalisations continued to rise at an alarming rate.

In those moments of prescribed national solidarity, it was hard not to resent the people around me, lining the sides of a street made up largely of detached houses and bungalows, all nicely spaced by over-attended gardens. We may have all been facing the same pandemic, but what did they know about the existential fears facing those close to me but now indefinitely cut off on the other side of the continent? The pandemic may have introduced uncertainty into these neighbours’ lives, but what was a little uncertainty amongst such apparent luxury?

My rejection of my surroundings extended to the beauty of the unassuming natural environment all around me. How could a place that cared so little about the rest of the world deserve to be so breathtakingly perfect with its ancient meandering lanes, abundance of spring flowers and lush greenery as far as the eye can see? How could a place bursting with perennial life be so detached from those who truly valued what it meant to be alive?

Unwilling to accept the cushy local conformity and unable to do nothing in the face of injustice, I resorted to a late night action to try and shake things up. I had done my best to preserve my energy in the early months of the pandemic in the UK by holding my tongue as the Conservative government badly mismanaged its response by firstly ignoring the threat, then playing it down before finally bumbling into a series of chaotic and often disastrous actions. But after a particularly galling example of cronyism, hypocrisy and dishonesty, I made my own poster with challenging statements about “truth,” “trust” and “democracy” and crept out after dark to anonymously pin up copies around the village.

And yet over time, as I passed my poster slowly fading in the phone box window on my daily walk, I came to feel a sense of unease about it. Not that my feelings behind the issues it protested had changed — they hadn’t. But in a small and tight-knit community such as this, where issues of “truth” and “trust” were lived experiences that bonded people together from all walks of life, I questioned whether this was really the right way to use my voice.

I had learnt through my job following protests, talks and discussions that principled defiance has its place. But as I gradually came to engage with the surprisingly diverse range of neighbours around me, I remembered that dialogue and compassion are equally important in affecting change — without these, we become trapped within our own bubbles and fail to see that the vast majority are doing what they can in their own way.

I’d been adamant when I first arrived back that the village of my childhood had nothing left to teach me. Yet, in its own unique way, each home leaves its mark.

What I learned from teaching girls how to fight

By Bronwyn Jones

I can tell you exactly why many people don’t want women playing sports: because it is a fuel rod for her rage. A rage of joy, anger and power. We are mocked for this in almost every other aspect of our lives. But in sport, she gets to feel stronger, more capable, more clever; she gets to fight and feel the joy of winning and the shit of losing — she gets to be herself. And the male world doesn’t matter. Her body is suddenly hers alone. It is not there for others’ judgment, gaze or control, but only for herself and her own happiness.

We separate boys from girls at some point in sport not because the girls “aren’t good enough” or “not strong enough” but because natural physical differences create a need for categories. People like to claim this categorical difference makes a difference in quality. But this is only so they can keep women and girls out of sport and control our bodies.

Everything can change when a boy looks at a girl he has been playing alongside for years and says, “I’m bigger and stronger than you.” Or when the boys foul her, or they won’t pass the ball to her they are making sure that she knows she isn’t supposed to be there. And we ask ourselves, who raises boys like this? To be abusive and police women’s bodies and freedom? Even when they are barely in their teens? All of us do, one way or the other.

The thing is — and this is something a lot of people don’t get — there is not much difference between the bodies of young boys and girls. And while strength and speed are important, so are skills, smarts and technique. Sport is 90% in your mind. So when we sit there assuming that male bodies are better than female bodies, that’s on us.

I thought the young generation would no longer have to deal with this, and that girls would no longer have to battle boys. But a while ago I saw it happen again.

I’ve been teaching kids rugby for a few years now. As is normal everywhere in the rugby world, I teach girls and boys together until tackling starts. It’s only when we hit each other that we separate.

Segregating the children before tackling begins would be for me an admission of the failure to teach the value of equality. It would mean I failed to make sure that all of the kids come up together as equals, and that girls know they have a place in sport too.

I worried about the girls leaving sports during their adolescence. Girls come under pressure during these years, pressure to be considered attractive, available or proper. These pressures can lead young women to suddenly drop sport. Because the girl who every boy wants to fuck isn’t fighting on the pitch.

So the pressure is on, especially in Kosovo, where for all its prowess and pride in sport, little is invested in the grassroots (where all those champions begin) and even less in girls.

Knowing all this, I thought I was ready to teach my girls to rage against this and channel it into their sport, to demand equality with the boys.

But in the end, I failed. I gave the girls my pep talk and told them to hold their space and be strong, that they are the best. I told the boys that their abusiveness was shameful and lectured them on sportsmanship. But in the end I separated the boys from the girls so the girls no longer had to hear how they aren’t good enough, when more often than not, they were better.

How can we talk about progress when young girls are still being told the same thing I was once told?

We can’t say we have progressed anywhere because our progress is temporal and limited — only some women get to fret about the glass ceiling. But even that privilege can just as easily be rolled back. Put aside the online activism, the advanced academic discourse or Women’s Day marches; women are still in the same place we have always been. We fool ourselves but we don’t fool the world.

VOICE MUTED, VOICE SHIFTED

What infuriates me is that she was trying to live better. She was almost there. Just as everyone is always trying, almost there, trying as long as one lives.

And while she was trying, she was shut down. Unplugged. Disconnected. Muted. Muted as if she was a noisy TV in a quiet place. Someone else called the shots. Not God. I wish it had been God, or something else. A car crash. An incurable disease. And that has to be the worst curse, begging for a different death, without the chance for a different life.

But I can still choose life, a choice she was deprived of, along with her body, place and voice.

Her body taken, mine altered. Her place lost, mine distorted. Her voice muted, mine to be found again. Pain. Pain. Pain. Pain in a dance with rage. But first, pain. She was killed. Breathe in, breathe out. Keep on swimming, until the storm clears. And if it doesn’t, I’ll build a new sun. One that warms us all.

Breathe in, breathe out. Ground. Let pain in. Open that can of worms, once and for all. Let it in, and let it out. Let pain dance with rage. But don’t join the choreography. Be the killjoy when there is no joy, there is nothing to be happy about. Let pain in. Don’t dance.

We won’t dance a dance orchestrated by someone else. We will not dance in a distorted world that expects us to dance while exploiting our bodies. Forcing us to dance. Forcing us out of our bodies, voices, places. We won’t dance.

We will shut the music down.

So my voice speaking her name can be heard.

So my voice speaking her name disturbs the lightness of those that kill and those that witness in silence.

So my voice speaking her name can once and for all

Disrupt.

Shift.

A reality taken for granted.

So my voice speaking her name

Can reach her,

underground.

Her body.

Her place.

Her voice.

So my voice can be heard.

Loudly.

So my voice echoes

And remains unforgotten. Unforgettable.

Authors:

Besa Luci

Aulonë Kadriu

Nidzara Ahmetasevic

Jack Butcher

Bronwyn Jones

Editing:

Daniel Petrick

Photography:

Atdhe Mulla

Feature Video:

Agon Dana

Typography & Illustration:

Arrita Katona

Production:

Dibran Sejdiu

Sound Mix:

Studio 11

- This story was originally written in English.