Just another day in a besieged city

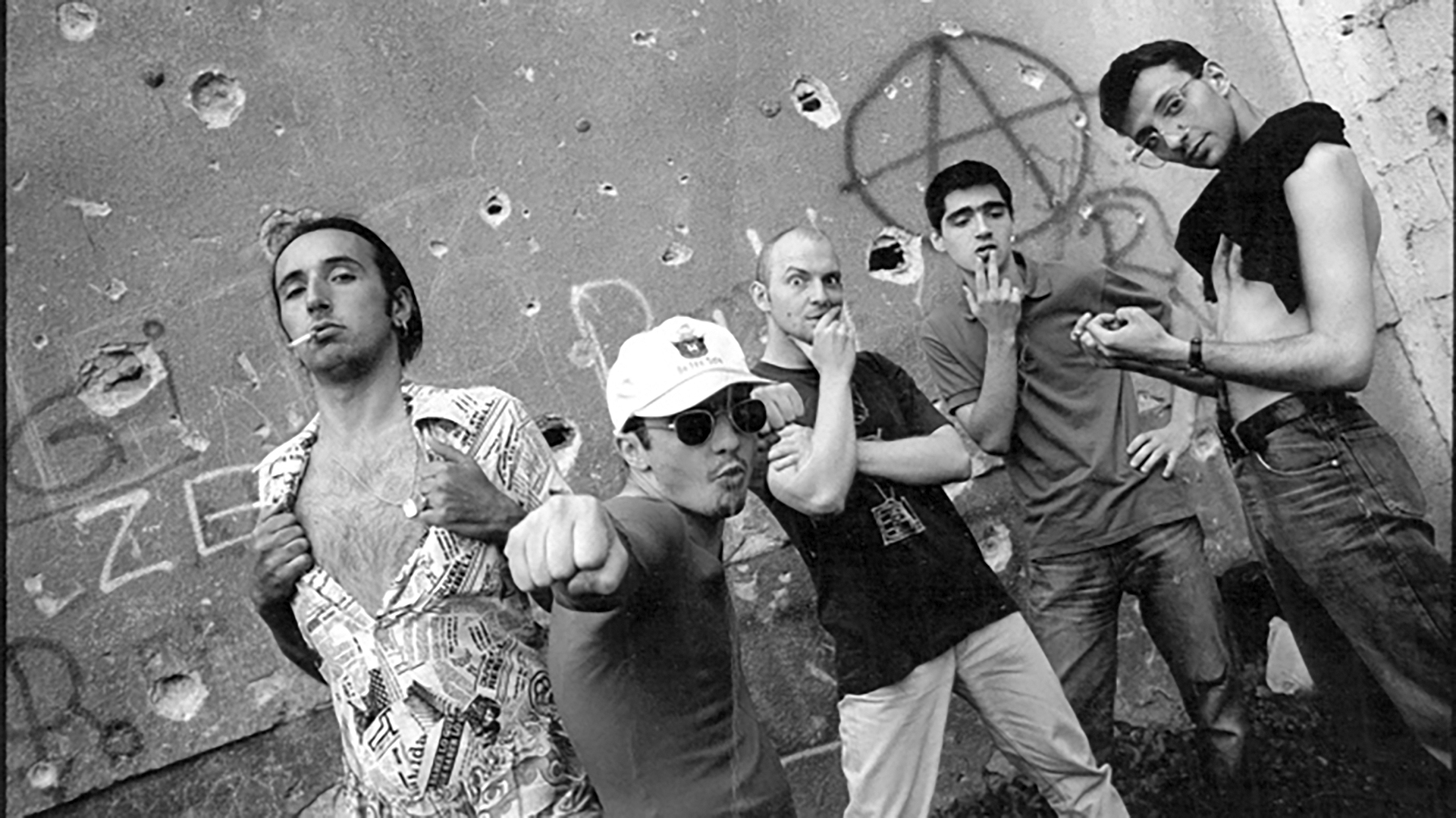

The Sarajevo punk scene kept rocking through the war.

So many people were ready to risk their lives for two hours of any music whatsoever.

A few more shells fell while we were lying on the garage floor and feeling ourselves to check if we were wounded.

For a moment, I imagine myself back on that stage, in the smoke, fog and haze of rock and roll.

Nebojša Šerić Šoba

Nebojša Šerić Šoba, a sculptor and musician, was born in Sarajevo, where he studied at the Academy of Fine Arts between 1989 and 1992. From mid-1992 until the end of the war in Bosnia and Herzegovina (December 1995), Šoba fought as a soldier in besieged Sarajevo. The journalist and comic book author Joe Sacco wrote a book on Šoba’s wartime experiences. In 1999, Šoba moved to Amsterdam, where he studied at the Rijksakademie, before he moved to New York, where he is based to this day.

This story was originally written in Serbian.