In 2013 Alban Muja did not know how to explain. At least, that’s the motto that gave name to his first and only solo exhibition at the National Gallery of Kosovo, “I Never Knew How to Explain…” Things may have changed since then.

The Mitrovica born artist opened the Pavilion of Kosovo at the 58th edition of La Biennale di Venezia 2019 on Thursday (May 9) at 2p.m. sharp. It marked Kosovo’s fourth participation in the prestigious arts event — this year themed “May You Live in Interesting Times” — and Muja’s first.

“I hope this justifies the money of the taxpayers,” Muja said, right after thanking President of the Assembly Kadri Veseli and Minister of Culture, Youth and Sport Kujtim Gashi for travelling to the Italian sinking city for the opening of the Kosovar pavilion. It was hard to tell if Muja meant to justify their delegation’s presence, or his own Venice project. Maybe both.

Anyhow, the presence of Kosovo in the Biennale has now become a must. Once again, the pavilion’s opening was attended by president of La Biennale Paolo Baratta, who has also shown his support on other occasions. “Kosovo is young in La Biennale and I love the young countries, because they believe more in what they do,” he said.

Those opening the Kosovo Pavilion included (left to right): Minister of Culture Kujtim Gashi; commissioner Arta Agani; President of the Assembly Kadri Veseli; artist Alban Muja, and curator Vincent Honoré. Photo: Atdhe Mulla / K2.0.

While the visitor sometimes doesn’t know whether they are in a competition for actual contemporary art or an economic and fashionable extravaganza, this is undoubtedly a highly demanding event for the arts community at home and abroad, and Muja knows it well.

For about six months, he has worked on the concept of “Family Album,” an arts project initially motivated by a picture that his family kept for years among their personal photographs.

In that image, smiley 18-year old Muja appears next to former Spanish Prime Minister José María Aznar, who donned a dark cap and his familiar dark moustache as he visited the Hamallaj refugee camp, near Durrës in Albania. It was here that Muja’s family had just reunited in May 1999 after days of exhausting travel through mountains in the cold and full of uncertainty about family and future.

That personal picture in his collection paved the way for Besa Luta, siblings Besim and Jehona Xafa, and Agim Shala, the four protagonists of the national pavilion whose stories are brought to the world’s attention for the second time in 20 years.

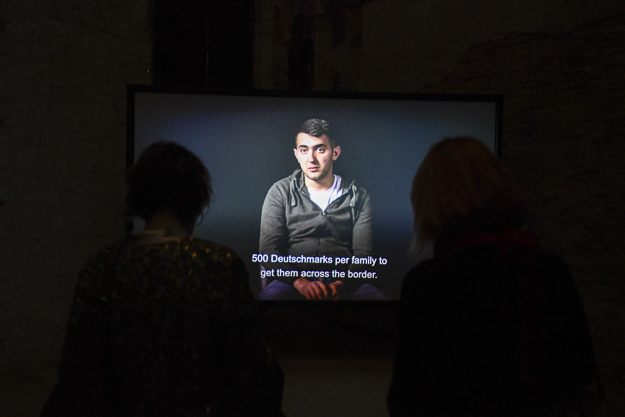

The pavilion presents a video installation in a dark and intimate atmosphere. Photo: Atdhe Mulla / K2.0.

Through three iconic photographs, Besa’s, Besim and Jehona’s, and Agim’s stories were told to the world before they could even acknowledge most of them themselves. Their stories were captured by famous war photo reporters Damir Šagolj, Peter Turnley and Carol Guzy and spread across the covers of international magazines, the Washington Post and other large international media.

It was 1999, and more than a million people, mainly ethnic Albanians, were on their way to Macedonia, Montenegro or Albania in search of safety, while the Serbian forces led by Slobodan Milošević continued their ethnic cleansing campaign in Kosovo. International photo reporters and journalists spread across the country to document and tell the world about what was to be the last war in Europe in the last millennium.

A daughter’s story

Back in ’99, Sherife Luta was a mother fighting for survival. Damir Šagolj’s photograph, which made the cover of Time magazine, depicts a woman walking in the line of refugees while breastfeeding her six-month-old baby, Besa, who is wrapped in a thick white blanket.

At the Kosovo pavilion — preceded only by the pavilion of Ukraine amongst other countries’ exhibitions in a large warehouse in the Sala d’armi in the city’s Arsenale area — visitors are confronted with Besa’s story right at its very entrance.

She tells of the circumstances that led to the picture, which was taken after an offensive at Ivajë village, on March 8, 1999. Besa’s mother did not know about her husband’s whereabouts, as he was a Kosovo Liberation Army (KLA) fighter. The women in the village had been captured and brought to the cultural center, before being freed.

Four protagonists, all children in 1999, tell the stories behind three iconic photographs taken during the Kosovo war. Photo: Atdhe Mulla / K2.0.

“We moved from village to village,” Besa says in the video. “My mother joined her neighbors. They said the lines were very long. There were around 7,000 [people].”

After long hours of walking, something happened that gives the visitor an idea of the hardships of their exodus.

“Before we got to Bllacë village, my mother stopped at her family house; there were many other refugees there,” Besa says. “And then, from the cold, I stopped moving. My mother thought I had died from the cold, and she fainted. Then a relative of mine covered me tightly with a blanket and put me in the stove. When she took me out, I started crying. All the refugees who were there applauded with joy.”

On their way to Bllacë, Šagolj took the Time cover photograph which is now one of the most memorable images of the Kosovo war. Another 30,000 refugees awaited at the cold camp, Besa recalls.

Walking through the pavilion

Inside the Kosovar pavilion, with its rectangular shape and red brick walls, the scene is dark, and the tone is almost intimate.

A couple of hours before the opening, the neighbors are noisy, as they prepare to fly an immense cargo airplane filled with the names of all living Ukranian artists over Giardini, the gardens of La Biennale, and the crowd is impatient to follow a live video of the endeavor. The things that happen in Venice.

Back in “Family Album,” the visitor must walk through a snaking circuit to see the videos on the three large screens hanging from the ceiling; they show a set of narrations in which the four protagonists explain the stories behind the three photographs, according to their recollections, or mostly according to what they have been told happened by relatives over the course of the years.

Agim Shala narrates the story behind the photograph taken by Carol Guzy at the refugee camp in Kukës. Photo: Atdhe Mulla / K2.0.

Muja had wanted the stories to be told by the children in the images, rather than by their parents, to give strength to the personal narrations. “They don’t have such a memory, or hate speech, they had more distance, they tell it as a story. For me it was very important to be quite… soft, detached of the emotion,” Muja said in an insightful interview with K2.0 before leaving for Venice.

To ensure visitors are in the intended space to experience the details of the narrators’ body language, which is not excessively emotional but neither emotionless, each of the speakers for each of the three screens had been positioned at a precise location in order to direct the visitors’ experience — if one were to be too far away from the screen, the narratives’ sound would fade away as memories do.

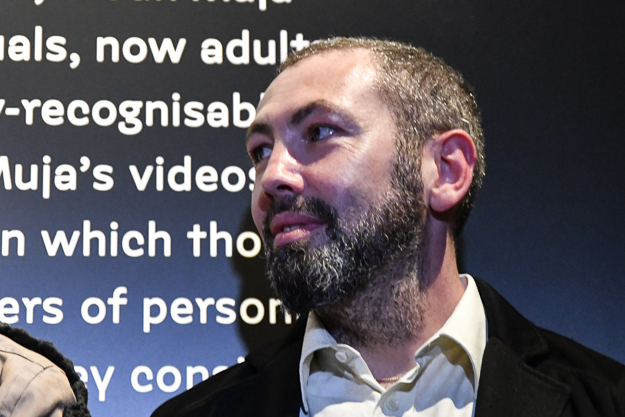

It is this sense of power over one’s narrative that Vincent Honoré, the chosen curator for the pavilion of Kosovo, wanted to particularly reflect upon through the work.

“Through their circulation, the images we chose were raising awareness about what was happening in Kosovo during the war, but the children in those images did not have any control over that circulation,” he says. “We decided not to use the original pictures because we wanted to give back to the people in these pictures that quality of being a subject and not just an object, being in charge of their narrative and their memories, and their own image.”

Vincent Honoré, curator of the Pavilion of Kosovo, is also director of exhibitions and programmes at Mo.Co Montpellier. Photo: Atdhe Mulla / K2.0.

One visitor to the pavilion, journalist Susanne Boecker from the arts magazine Kunst Forum, pointed out the reflection the work makes on photography today.

“All the people in these videos have some sort of image that accompanies them during their life, a single image with very strong meaning,” she said. “It makes you think about the strength of the media and how big the worth of a photograph can be — [it also speaks] about how the impact of the image has been lost, it doesn’t accompany you, it is not in print, and without attempting to do that this work speaks about the change of the medium.”

For Branko Franceschi, who happened to know Muja’s work as he heads the Museum of Fine Arts in Split, Croatia, agreed: “It’s very beautiful how Alban combines the story of the media and the narratives of history,” he said.

It’s precisely the changing face of photography that Honoré pinpoints as one of the subtle achievements of “Family Album.”

“It’s absolutely one of the concepts behind the work, to investigate the role and impact of the images, as well as their circulation, how they are distributed, seen by others, and how they can lose their meaning [by being misinterpreted],” says Honoré, who is part of the Biennale as curator of a national pavilion for the first time. “It’s a very contemporary work, and it goes beyond what Alban has done before.”

Unfreezing the memory

The second story one encounters on their path forward is Jehona and Besim’s. Their story, captured in the photograph taken by renowned photographer Peter Turnley and splashed across the Newsweek mag cover in ’99, is one marked by the disappearance of their father, a school caretaker from Mitrovica — it is a tale of torture and hope to find each other, and one of love.

Their recollection tells the fate of their father, Mustafa Xaja, who was taken prisoner by Serb forces. Until April ’99, Mustafa had been working in the Migjeni school. One day, he came back home and told his family: “The war is approaching. Whatever happens we will be prepared.”

What came later was probably far from their imaginations. Mustafa was arrested at Mitrovica’s bus station one day and was subsequently divided from his wife and children until the end of the war.

“They put us in a line of people walking to Drenicë,” recalls the son. In the meantime, they were uncertain about whether their father had been sent to the prison at Smrekonicë or at Pozarevac (one from which they thought he would not come back alive).

Later, after being brought back to Mitrovica again, the children asked around for their father, receiving all sorts of contradictory responses about his whereabouts.