Letter from a friendly ‘inadmissible’ person

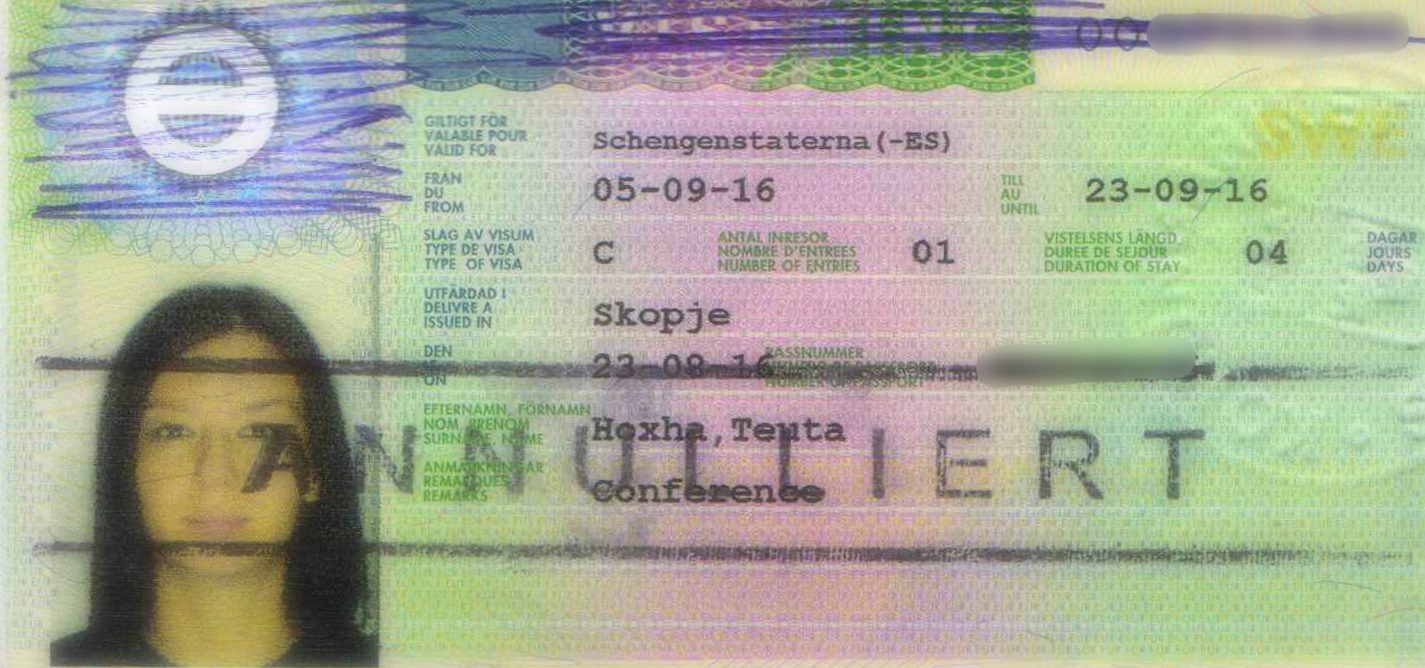

Human rights activist describes Schengen visa annulment experience.

There I was, a human rights activist from Kosovo, attempting to defend my right to information on the whereabouts of my travel documents, in a European Union country.

Teuta Hoxha

Teuta is acting executive director at YIHR KS. She joined YIHR KS as a program coordinator in 2015. Earlier she also worked for FDH Kosovo, monitoring war crime trails and other penal actions that are ethnically and/or poltically motivated. Teuta worked for many years as a coordinator at KOMRA Coalition in Kosovo, as well as in two projects of FDH and FDH Kosovo, “Batajnica Memory Initiative”, and the Regional School for Transitional Justice. In June 2015, she was picked by KosovoLive360 as Woman of the Week. Teuta works towards the achievement of a society that respects human rights and encourages facing the past. She has finished law school and is interested in archeology.

This story was originally written in English.