Lost in my own culture

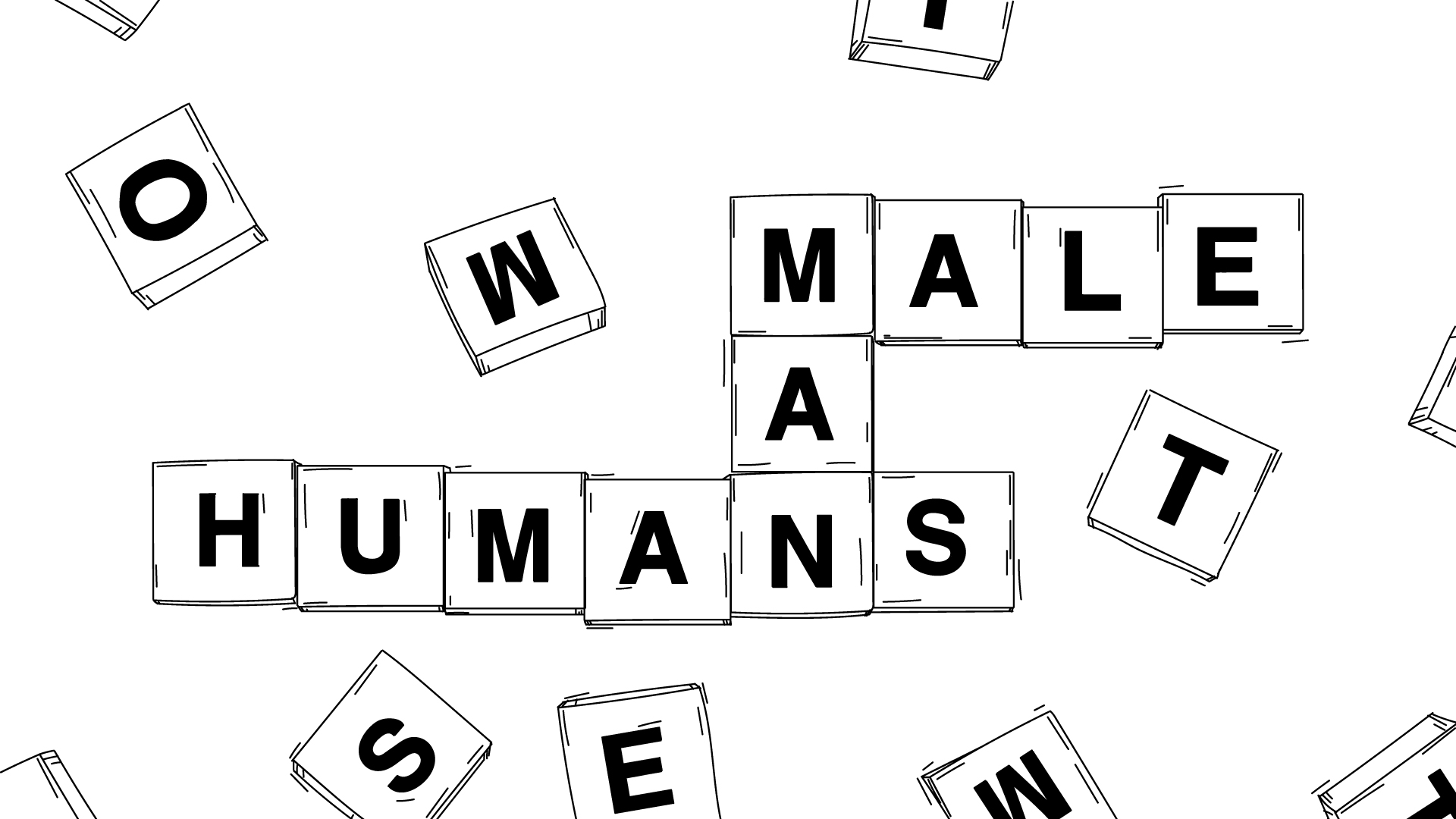

Our language still excludes women.

Did this mean that I, as a girl, had no place in the home I was brought up in?

Young girls are taught to never be angry.

The language we use comes as a result of long-standing socialization, mirroring our history and defining the way we act.

Gladiola Lleshi

Gladiola Lleshi holds a bachelor’s degree in law and will be starting her master’s studies in International and European law at Erasmus University Rotterdam. She is particularly passionate about the connections between law, public policy and gender.

This story was originally written in English.