Each day, as part of his daily routine, Ilir Mustafa pulls on his blue jacket, gloves, brown apron, protective mask and special shoes. Wearing the uniform and protective equipment are a prerequisite of entering the practical work lab in the Shtjefën Gjeçovi vocational school in Prishtina, where he is learning to be a welder.

As you enter the practical work lab for welding, you notice warning signs calling for increased care and providing instructions for safety at work. A long table with equipment is in the middle of the classroom; on the left there is a huge piece of machinery for cutting metal sheets, and in front are the workstations, covered with black curtains.

Ilir and his fellow 11th grade students use these spaces to practice the profession that they have chosen. The work process requires dedication and finesse — when using welding equipment, in Ilir’s words, “you have to be precise, focused and you mustn’t be afraid.”

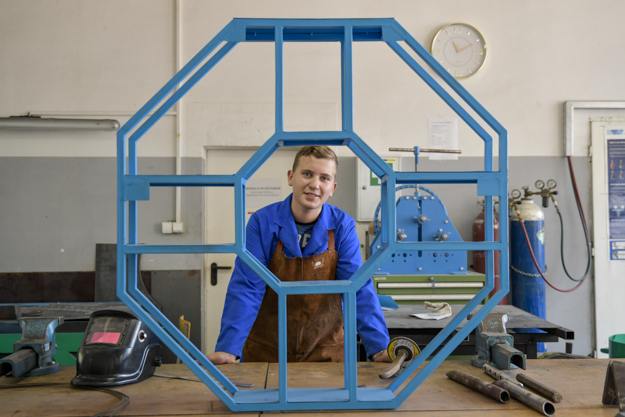

One of the study streams for students at the Shtjefën Gjeçovi vocational school is learning to become welders, a profession in high demand from employers. Photo: Atdhe Mulla / K2.0.

He starts the process by melting a metallic sheet with a hot flame, before cleaning it with a brush to remove the residue and finally placing it in a cauldron full of cold water. The best welded models are exhibited in order to inspire students.

“I chose this field because there is less theory and more practice, there is more work, and I know that I’ll have a profession, a diploma, so I won’t have to worry about finding a job,” says Ilir, adding that he has made the right choice.

According to Ilir, his brother, who also went to the same school, found a job really easily after finishing school. He is convinced that he will have the same fate.

But many students do not feel the same. Ilir tells about how he was judged by his friends and former classmates because of his choice of school.

“They asked me why I went to that bad school, saying that only students who do not manage to enroll in other schools go to this school — because they saw that I had good grades,” he says. “Most people see it as a school that only bad students go to, but I would say that it’s better than most gymnasiums and should not be underestimated.”

Ilir Mustafa believes he won’t have a problem in finding work once he leaves school and is confident that he made the right educational choice. Photo: Atdhe Mulla / K2.0.

Ilir’s experience is far from unique. Vocational Education and Training (VET) in Kosovo is faced with stigma, and enrollment in such schools is often seen as a secondary alternative for students who do not manage to enroll in gymnasiums when they change schools in grade 10.

The primary objective of vocational schools is to prepare students for the labor market, to create different worker profiles and to provide opportunities for continuing with university studies, all through a combination of theoretical teaching and vocational practice. However, persistent issues when it comes to budgets, curricula and harmonizing with labor market demands means its an educational sector that faces a series of challenges.

Crunching the numbers

Kosovo has 66 vocational schools in total, providing 140 different worker profiles. They are regulated by the Law for Vocational Education and Training “in accordance with social and economic development needs … including technological and economic changes, labor market demands and needs of individuals in relation to the market economy.”

Shtjefën Gjeçovi vocational school provides three-year programs in mechanics, textiles and transport and, despite the impression given by the old building from the outside, is one of the best equipped vocational schools with good conditions for conducting practical professional work. On the ground floor there are workshops for practical learning, while the classrooms for theoretical learning are on the first and second floors.

In one of the workshops there are tools that students can use to practice a method of mounting heating and air conditioning units. Radiators are exhibited as models of equipment mounting, with the pieces that students work with placed next to the radiators. Five types of vehicles are parked in the next room; they are mainly donations that serve to teach future car mechanics.

In the textiles classroom, there are tables with sewing machines, materials folded at the edge of the room and examples of clothes made by students exhibited on the walls to help create a good working atmosphere.

Prishtina’s Shtjefën Gjeçovi vocational school is relatively well equipped, but other vocational schools throughout Kosovo struggle for the necessary resources. Photo: Atdhe Mulla / K2.0.

But not all vocational schools in Kosovo have the necessary conditions and equipment for practical work. In many it is not possible to conduct practical teaching properly in certain subjects due to a shortage of equipment and suitable spaces.

According to the Kosovo Education and Employment Network (KEEN) — a strategic coalition of civil society organizations focusing on the fields of education, employment and social policies — one of the main problems is the budget, which is insufficient to cover the elementary needs for the proper functioning of a vocational school.

Public VET institutions are financed by Kosovo’s central budget via specific allocations for education through the Ministry of Education, Science and Technology (MEST). Of the 73 million euro MEST budget for the year 2019, only 3.6 million euros — or 5% — has been allocated to the Agency for Vocational Education and Training and Adult Education, with an additional 59,000 euros set to come from generated income. The funding is allocated for staff salaries, goods and services as well as municipal spending.

KEEN’s monitoring report titled Vocational Education and Training in Kosovo: Challenges and Opportunities, which was published in April this year, states that the allocated funding is not enough: “Despite the fact that strategic documents have been produced to improve the vocational education sector, in reality, schools face difficulties in producing qualitative education for students, mainly due to the lack of financial resources.”

Article 33 of the Law for Vocational Education and Training specifies that when allocating the budget for VET institutions, specific demands related to “material equipment and other spending for practical training” must be considered.

A Kosovo Education and Employment Network report found that vocational education in Kosovo is underfunded and that further changes are required to the method of funding. Photo: Atdhe Mulla / K2.0.

Despite this, the KEEN report states that the formula for financing pre-university education does not consider the needs of vocational schools regarding the implementation of practical learning, and as a result students are not properly trained and educated.

“Although this formula implies financial autonomy, further decentralization of VET institutions is necessary to enable good planning and guidance, as well as independent management in these schools,” the report finds. “This can be achieved by allocating the budget in accordance with school priorities. It is essential to create a flexible budget for VET institutions, so as to fulfill the demands of different VET profiles, seeing that expenditure differs to a great extent.”

Furthermore, the report finds that the current form of financing for education does not take into consideration the specifics of vocational education and training, even though current legislation enables vocational schools to receive additional funds from other activities, such as organizing courses in addition to those that are financed by public funds, or donations, gifts and other sources that are permissible by law.

“Bureaucratic and administrative procedures for generating income must be simplified, and VET institutions must be encouraged and stimulated in this regard,” the KEEN report says.

The report, among others, is based on the Kosovo Education Strategic Plan 2017 – 2021, the base document for the development of Kosovo’s education sector, with KEEN highlighting that while the Strategic Plan identifies the sector’s shortcomings, if it is not reviewed to fit the needs of vocational education then the situation will not change.

But Valbona Fetiu-Mjeku, head of the Division for Vocational Education and Training within MEST, says that they are already working to improve the way in which VET schools are financed. “We believe that after completing the process of reviewing the formula for financing the whole [pre-university education] system — which is being supported by the World Bank — we will take into consideration the cost per profile/sector in vocational schools,” she says.

Connecting all the pieces

In addition to vocational school budgets, the law also regulates curricula, the development of which is foreseen to be “in accordance with relevant standards of qualification, the profession and the education sector.”

However, according to Agnesa Qerimi, director of the Kosovar Youth Council (KYC), an organization that works to empower youth through education, “the current legislation is well-written, but not properly implemented.”

“The Curriculum Framework is notably harmonized with highly sophisticated practices that are implemented in European [Union] countries, but in our country, it lacks in practice,” Qerimi says.

Shtjefën Gjeçovi school headmaster Faik Salihu also sees the issue of curricula as problematic.