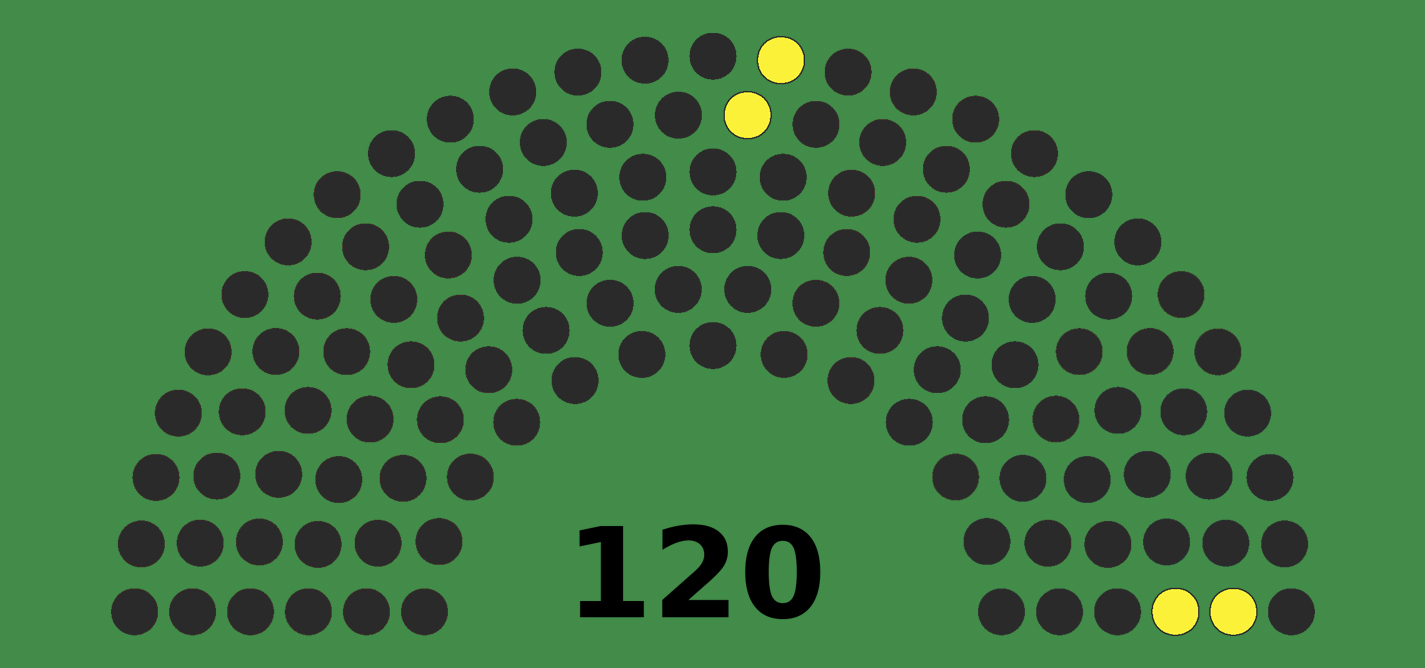

Minority political representation: Roma, Ashkali and Egyptians

First of a 5-part focus on those representing Kosovo’s minorities.

The Roma, Ashkali and Egyptian communities in Kosovo are amongst the most discriminated against, poorest and vulnerable in Kosovar society.

“When Majlinda [Kelmendi] succeeded in judo, Albanians were congratulated everywhere — on TV, in newspapers and elsewhere. That made me and my community feel bad, because we were also happy about her successes."

Veton Berisha

Eraldin Fazliu

Eraldin Fazliu is a former journalist at Kosovo 2.0. Eraldin completed his Master’s on ‘European Politics’ at the Masaryk University in the Czech Republic in 2014. Through his studies Eraldin became interested in the EU’s external policies, particularly in promotion of the rule of law externally. He is a passionate reader of politics and modern history.

This story was originally written in English.