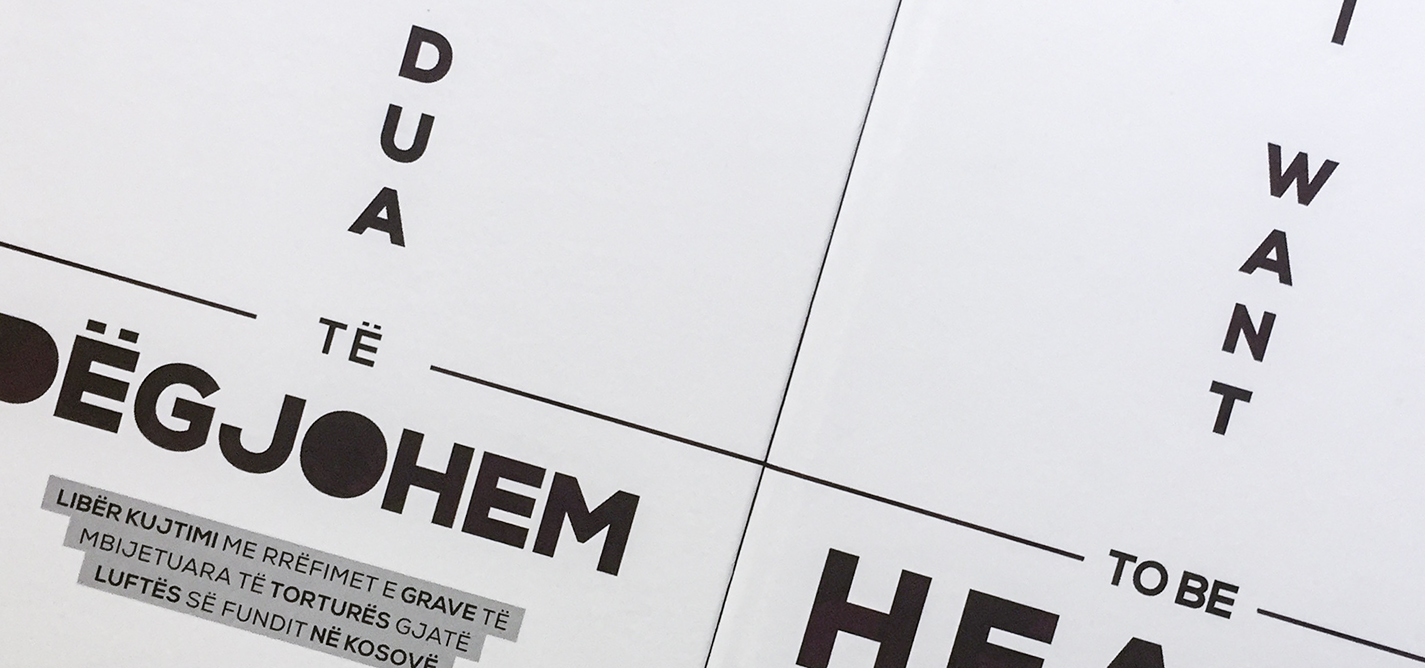

New memory book on wartime sexual violence

Ten survivors tell their personal stories.

"Unfortunately because of the stigmatization prevalent in society people haven’t had the opportunity to listen to these stories.”

Atifete Jahjaga.“NGOs have faced direct threats because the community wanted to keep this issue as a taboo.”

“There hasn’t been any war in which sexual violence didn’t happen because it is a weapon of war and a strategy."

Vjollca Krasniqi

Dafina Halili

Dafina Halili is a senior journalist at K2.0, covering mainly human rights and social justice issues. Dafina has a master’s degree in diversity and the media from the University of Westminster in London, U.K..

This story was originally written in English.