It has almost become common to see Xhelal Gora standing in front of the entrance of the oncology clinic at Prishtina’s University Clinical Center of Kosovo (QKUK). Most weeks — for four or five hours — he waits for his brother, Ruzhdi, as the latter finishes chemotherapy. The 43-year-old was diagnosed with cancer three years ago and has since undergone seven surgical interventions.

Now, Ruzhdi needs medical treatment at least two or three times a week. His treatment starts in the morning, with the Gora brothers having to get up early and travel for over an hour from Kaçanik to the capital.

Xhelal waits in case he needs to go and get medicines that cannot be found in the clinic; often, he needs to buy these from private pharmacies.

For the Gora family, having to buy the medicines only adds to the woes of Ruzhdi’s illness, as their financial situation causes continuous concern. Shortly after Ruzhdi experienced the first symptoms, his family decided to sell a piece of their land in Kaçanik.

Families of people with serious illnesses are often required to find their own medicines or to have tests carried out in private clinics. Photo: Atdhe Mulla / K2.0.

Xhelal explains how they need to pay approximately 400 euros per month to treat Ruzhdi’s illness. “We have secured the medication ourselves many times,” he says.

At times, the sum has been even higher. “He has often undergone scans and treatment in private clinics. They would tell us that it was either this, or nothing at all,” he says, referring to the oncology clinic’s deficiencies. The cost of return transportation from Kaçanik to Prishtina — 10 to 15 euros a week — added to the family’s outgoings.

Before becoming ill, Ruzhdi worked as a salesman at a market that was owned by their neighbor. After experiencing symptoms, the father of three found it impossible to continue working, but he had already been facing financial issues.

“It would help if medication was free. Actually, it would help a lot.”

Xhelal Gora

Xhelal explains that after his brother was diagnosed with cancer he decided to go and work in Germany, where he stayed for about two years. He used the money he made working in construction to ensure that Ruzhdi didn’t lack the medication he needed. He says that they have spent 15-20,000 euros treating Ruzhdi’s illness up until now.

As well as a way of funding Ruzhdi’s medication, Xhelal’s salary was also the main source of income for his family and that of his brother. “All his kids are younger than seven,” says Xhelal, with tears welling up in his eyes.

Last year, Xhelal returned to Kosovo to care for his brother, but he is currently unemployed.

“Our [economic] situation is very difficult,” says Xhelal, adding that the only aid they have received in three years was a 100 euro donation from the Municipality of Kaçanik, and nothing at all from the Ministry of Health. “It would help if medication was free. Actually, it would help a lot.”

Paying out of your own pocket

Oncologist Arben Bislimi, who has worked at the oncology clinic for many years, says that they are aware of the financial difficulties that patients face as they witness their struggles on a daily basis. According to Bislimi, this directly influences his profession and the medical condition of patients.

“If a patient undergoes a cycle that costs more than 100 euros, this puts a strain on the family budget,” he says, highlighting that cycles of treatment are conducted every two or three weeks.

The oncology specialist explains that this situation has forced many patients to wait until the clinic is supplied with medications that are often lacking and that this is directly linked to the worsening of patients’ conditions. If, for example, it is determined that a patient needs to undergo therapy every three weeks and the patient is forced to go beyond that time frame without receiving treatment, Bislimi says that “at that point you are off course, and as such are not guaranteed the result that is expected after undergoing complete therapy.”

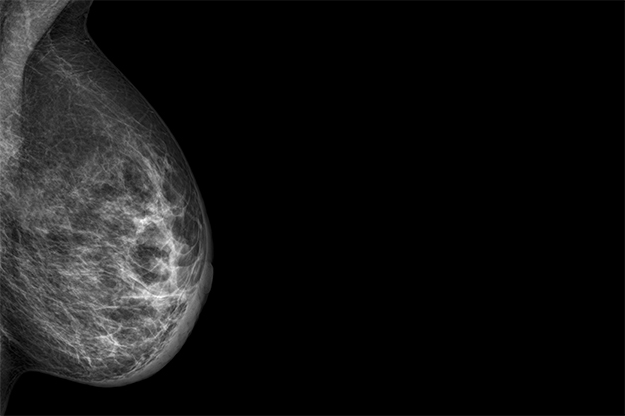

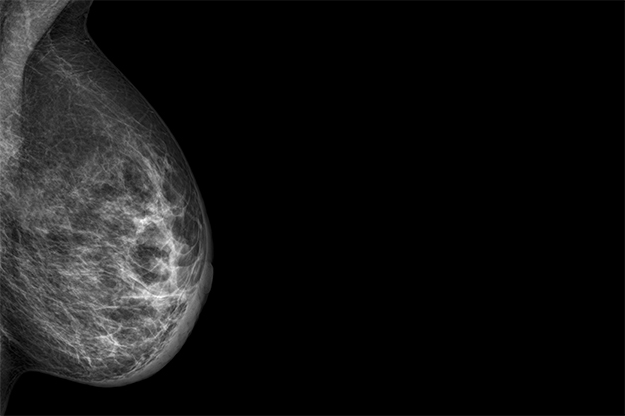

Herceptin is often used to treat patients with breast cancer, but in Kosovo it has to be brought privately and it’s huge price makes it prohibitive to most of those who need it. Photo: Creative Commons.

The difficulties posed by the lack of supplies are also highlighted by another oncologist working in the oncology clinic at QKUK, Faton Sermaxhaj. As an example he takes patients who are treated with Herceptin — a drug often used to treat breast cancer. According to Sermaxhaj, this treatment costs 3,000 euros per time, and with patients needing it every three weeks this adds up to 50,000 euros per year.

“Every year we have 350 new cases of people affected by this type of cancer,” says Sermaxhaj, explaining that not all patients are treated with Herceptin, and adding that this treatment is necessary for about 40 percent of patients.

The cost of Herceptin is prohibitive for most patients. In these circumstances, Sermaxhaj explains that they try to use other medicines, while not veering from the course of the necessary treatment. However, he goes on to say that in most cases, replacement medication does not do the job and is not always available in the clinic regardless, although it does have around 70-80 percent of medication for ‘basic therapies.’

“We are also part of this society. You understand that you are putting a strain on their economic situation, and you have no way to help because there is a shortage of medication.”

Arben Bislimi, oncologist

Bislimi suggests that this year the supply of medication has worsened compared to the past couple of years — particularly in the past couple of months. For Bislimi, this is one of the most difficult situations in his professional career.

“We are also part of this society. You understand that you are putting a strain on their economic situation [because they have to buy medicines], and you have no way to help because there is a shortage of medication,” he says.

In November 2017, the minister of health, Uran Ismaili, and the president of the Assembly, Kadri Veseli, visited the oncology clinic, promising to support it.

“Until the Law on Health Insurance comes into force, no patient in the Republic of Kosovo will have to pay for essential medication,” said the president of the Assembly. Minister Ismaili promised “to review the Essential Medicines List” to ensure it “meets all of the needs” of the oncology clinic.

During this visit, Veseli stated his appreciation for the work that is being done in the oncology clinic, further promising to supply this institution with equipment and to provide extra staff, specifically nurses and specialists.

Seven months later, oncologist Sermaxhaj highlights that one of the difficulties that the clinic continues to face is a shortage of nurses. “We have a big shortage, and this is being reflected in oncological work,” he says, explaining that they currently only have 10 nurses, and that five of them have been hired recently. He goes on to say that this figure is still insufficient.

Oncologist Arben Bislimi says that the QKUK oncology clinic is experiencing its worst medicine shortages in years, while staff numbers are also too low. Photo: Atdhe Mulla / K2.0.

Bislimi also states that the number of oncologists — 20 in total — is also not enough, going on to say that “the Ministry must provide specialists for this field.”

He also believes that more must be done regarding medical equipment. “In radiotherapy we have two pieces of equipment, one for curative treatment and the other for palliative care,” he says. “Up until now they have served their function, but with time, they have started to deteriorate.”

According to Bislimi, they must be serviced or changed completely, and new equipment must also be introduced, as the number of people affected by malignant illnesses is on the rise, meaning the clinic must increase its capacities.

Seeking remedy abroad

Such systemic problems inevitably contribute to a lack of trust from citizens toward the health care system. When faced with serious illnesses, many citizens see their best chance of survival as seeking treatment abroad.

Nafije Latifi was running a cultural magazine up until 2004, when she was diagnosed with breast cancer. The news shocked her, but the situation she would find in public hospitals would only add to her despair. According to Latifi, QKUK had many issues, so much so that she was forced to undergo diagnosis and medical treatment in private clinics.

“At QKUK, there was no equipment or other tools. Many radiologists and pulmonologists would do the work of oncologists,” she says, further explaining that to get a diagnosis she “had to go from one private clinic to another,” undergoing “ultrasound, X-ray scans, biopsies, mammographies, cytology tests,” all of which she paid for herself.

Nafije Latifi says that before being diagnosed with breast cancer she was forced to go to various private clinics to undergo essential tests, as fundamental equipment was not available at QKUK. Photo: Creative Commons.

Troubled by the whole affair — from the inability to be cured in her home country, to the lack of trust in doctors and the shortage of medical equipment — Latifi decided to seek treatment abroad, traveling to Germany to undergo surgery.

Her troubles started when she had to deposit 10,000 euros into the clinic’s bank account so that she could receive the warranty she would need to apply with at the German Embassy. The next step was securing additional funds for the required surgery.

With the help of family and friends, she managed to raise the funds to go to Germany. She does not wish to specify the cost of her treatment, but says that it was “extraordinarily large” and that it “took a toll on the family budget.”

Latifi insists that she was lucky, rhetorically asking: “What about people who don’t have these opportunities?” She answers herself: “Families collapse.”

Fjolla Gjonbalaj was also faced with having to quickly raise funds for treatment abroad when her first child developed serious health problems shortly after being born in 2012. Three days after giving birth, the baby boy experienced his first symptoms — he was very pale.

Gjonbalaj reacted immediately, taking her son to be checked at the pediatrics department. The doctor said that the boy was suffering from jaundice and that it was nothing serious. For a few months, Naron was taken to see the same doctor.

Public funding private

In 2002, the inability to cure serious illnesses in Kosovo’s public health care sector pushed institutions to establish the Program for Medical Treatment Outside of the Public Health Service. This fund was an attempt to provide financial aid to patients suffering from serious illnesses, to enable them to seek required treatment in the private system, or abroad.

Up until 2012 — almost every year — the budget of the fund was 2 million euros. This increased year on year, although seemingly not enough to meet demand.

By 2015, spending on the fund reached 7.8 million euros, despite only having 6 million euros having been initially allocated in the annual budget. Despite the fund having quadrupled in a matter of years, about 820 patients still saw their applications to the fund rejected.

The fund’s budget has subsequently continued to increase; in 2017, 11 million euros were spent, covering the costs of over 1,400 patients from around 2,000 applications.

In early 2018, deputies in the Parliamentary Committee on Health, Labour and Social Welfare called on the Ministry of Health to invest these funds at home in the University Clinical Center of Kosovo (QKUK). They argued that the funds should be used for required medical equipment and supplies, because the medical staff at this institution are sufficiently capable of dealing with serious illnesses.

Two months later, Gjonbalaj took her son to be checked by another doctor. As soon as he saw Naron, he asked whether or not he had undergone liver tests. When his mother said “no,” the surprised doctor advised them to conduct these tests as soon as possible, issuing a written directive. Gjonbalaj took her son to get the tests done, and afterward went to the same doctor, who advised her to seek treatment from an infectious disease specialist, as the baby’s medical condition did not look promising.

The infectious disease specialist told her that the baby’s condition was not a serious one, and that he was actually suffering from a simple infection. At this point, Gjonbalaj became sceptical of the doctors and decided to seek another opinion. The fourth doctor who checked Naron said that his condition was very bad and that he urgently needed to be hospitalized.

Naron was hospitalized at QKUK’s Pediatric Clinic, where he stayed for more than a week, during which time doctors were unable to offer a diagnosis, only adding to Gjonbalaj’s concern. Meanwhile, her brother and cousin living in Germany managed to set up an appointment at a German hospital.

Intent on taking her son to Germany for treatment, Gjonbalaj demanded Naron be released by the hospital. “You can go wherever you like, but there is no cure for your son,” Gjonbalaj says she was told by a doctor.

She was baffled at how a doctor could say such a thing when they were yet to diagnose her baby. She insisted on his release, and with an invitation from the German hospital, she went to the German Embassy, where she received a visa that very same day. Two weeks later, Gjonbalaj, her husband, and their son Naron, went to Germany.

After undergoing medical analyses, on December 12, 2012, Naron was diagnosed with a rare illness that required a liver transplant, and a donor. In addition, the surgical intervention would cost over 125,000 euros.

Not having the necessary funds for their son’s treatment, the Gjonbalaj family were forced to seek help. Through a public campaign, they managed to raise the funds in a period of only six days, even raising an extra 15,000 euros, which were donated to children in Kosovo who were suffering from serious illnesses.

Naron underwent a successful liver transplant in March 2013, with his father as the donor, and five years on he is in good health.

However, his mum still retains the scars of their traumatic experience of the Kosovo health care system, and doesn’t dare to think what would have happened if they hadn’t been able to secure treatment for Naron abroad.

“I feel obliged toward the people,” Gjonbalaj says. “If they hadn’t helped, I don’t know how we would have achieved this success for Naron.”K

Feature image: Atdhe Mulla / K2.0.

Edited by Leurina Mehmeti and Jack Butcher.

Back to Health Monograph