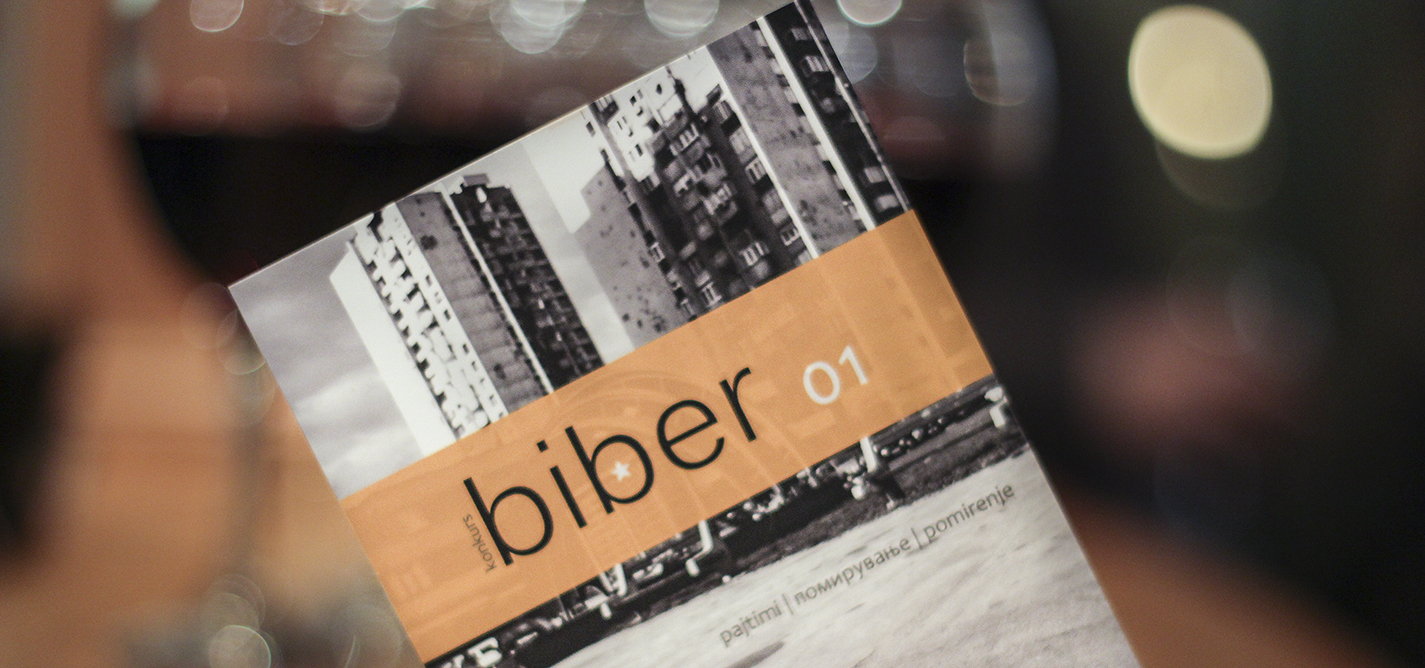

Regional project promotes reconciliation through writing

Short stories by authors from former-Yugoslavia aim to reconcile the bad blood between nations.

Valmir Mehmetaj

Valmir Mehmetaj is a journalist who has previously worked in TV journalism and as a staff writer at Kosovo 2.0. Valmir studied communication sciences at the South East European University in Tetovo, Macedonia. He believes deeply in constant learning and forming original thoughts, and mainly writes about cultural and social issues.

This story was originally written in English.