Running to live

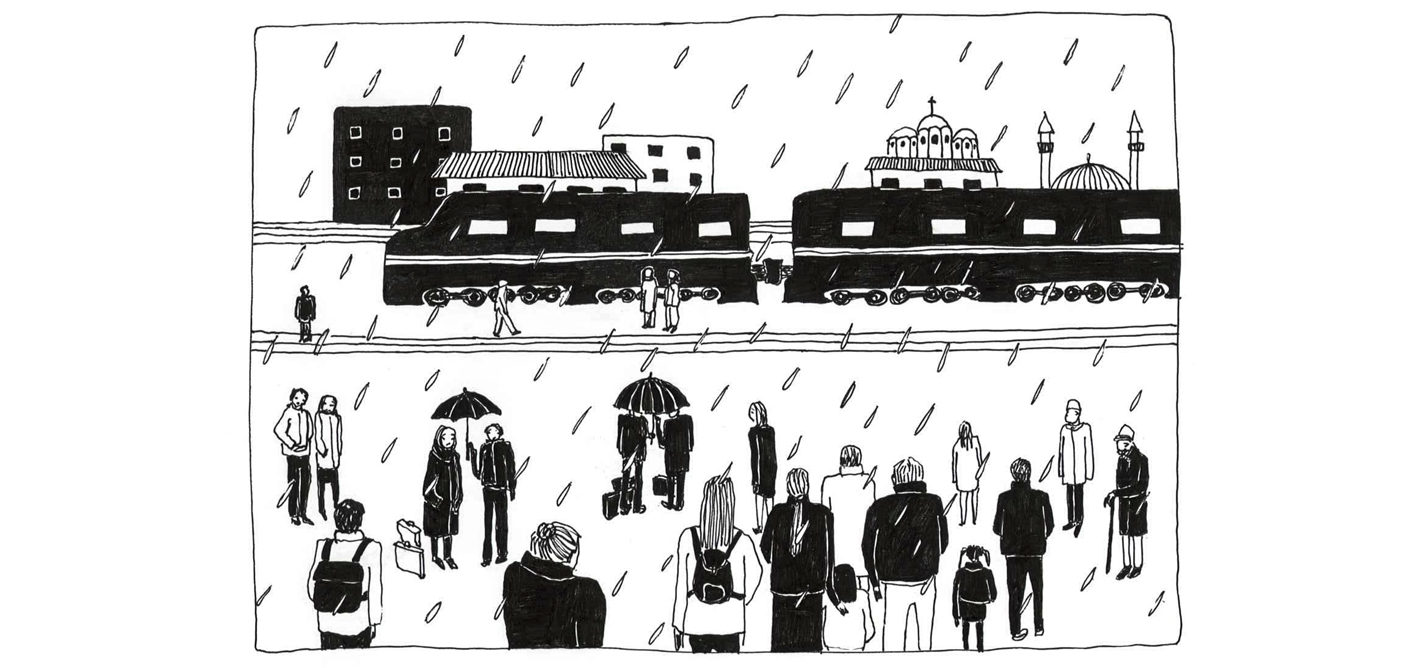

NATO's intervention brought hope, but also retaliation, forcing many to flee their homes.

Our ears were always waiting for the terrible sound of tank chains hitting asphalt.

That was the moment I understood what a mother is ready to do for her children.

Eraldin Fazliu

Eraldin Fazliu is a former journalist at Kosovo 2.0. Eraldin completed his Master’s on ‘European Politics’ at the Masaryk University in the Czech Republic in 2014. Through his studies Eraldin became interested in the EU’s external policies, particularly in promotion of the rule of law externally. He is a passionate reader of politics and modern history.

This story was originally written in English.