In April 1990, Adem Demaçi was released after 28 years of imprisonment. This was the result of three sentences by the Yugoslavian state, making him one of the political activists who served the longest prison sentences in ex-Yugoslavia. Around two decades after being released, when asked whether he had at any point considered escaping from prison, he answered: “Does a man escape from his place of work?”

Demaçi was first arrested in November 1958 when he was 23 years old, as he was accused of “hostile activity against the state regulation of the Federal People’s Republic of Yugoslavia (FPRY).” He was sentenced to five years in prison at the time, but was released after three years. It was a time when many people were murdered by FPRY authorities and many more were raided, imprisoned and forcefully deported to Turkey.

In June 1958, Demaçi published a book titled “Gjarpijt e Gjakut” (“Snakes of Blood”), in which he criticized the tradition of blood feuds between Albanians, the massive and violent deportations of Albanians to Turkey, and called for revolt against the Yugoslavian regime. His book was banned the same year, and he met other in prison who were there simply because they had been caught with his book.

In 1963 — when the federation changed its name to the Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia (SFRY) and (re)confirmed Josip Broz Tito as “President for Life” — Demaçi established the Revolutionary Movement for the Unification of Albanians, the members of which pushed for the unification of Kosovo and Albania, and vocally protested the economic marginalization of Albanians in former Yugoslavia.

He was arrested again in 1964 and released in 1974, when the SFRY ratified a new constitution, which foresaw more rights for the republics and their provinces. However, dissident political activists continued to be persecuted — Demaçi was arrested once again a year later, and sentenced to another 15 years.

After being released from prison, Demaçi continued his political activism during the 90s, a time when Slobodan Milošević’s oppressive regime excluded Albanians from public spaces, institutions and places of work.

His opinions about the development of the resistance placed him in open conflict with Ibrahim Rugova, leader of the LDK and the president elected by Kosovo Albanians. In August 1998, Demaçi became a Political Representative of the KLA, a post at which he remained until March 1999, when he resigned as a result of his disagreement with the signed Rambouillet Agreement. He was particularly opposed to the points that foresaw the preservation of Serbia’s territorial sovereignty, which included Kosovo, and the presence of Serbian forces in Kosovo territory.

After 1999, he worked to protect minorities in Kosovo and was one of the most active voices that called against revenge toward these groups in the early postwar years. Demaçi was also critical of the international community, which according to him did not respect the decisions of locals.

One year ago, on July 26, 2018, Demaçi died at the age of 82.

K2.0 spoke to Shkëlzen Gashi, the author of Demaçi’s biography and the man who asked him whether he ever thought about escaping from prison.

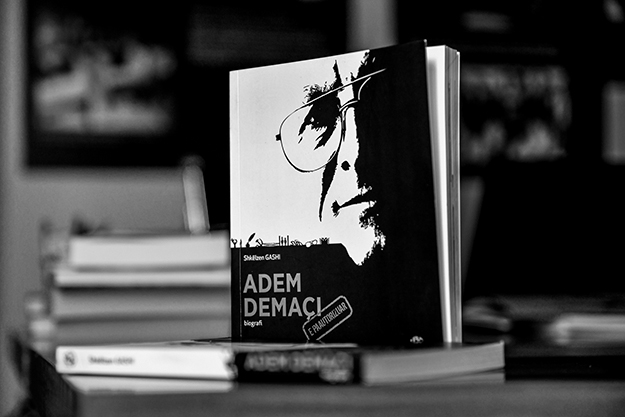

Gashi and Demaçi had many conversations from 2008 until 2010, based on which Adem Demaçi’s autobiography was due to be written and published. However, their relationship took a turn for the worse before the book was published. According to Gashi, this happened because Demaçi demanded to erase a few pages from the book. Gashi’s book, “Adem Demaçi, biografi e paautorizuar” (“Adem Demaçi, an unauthorized biography”) was published without Demaçi’s authorization in 2010.

K2.0: Let’s begin by talking about the post-WWII period in Kosovo, up until the first time Demaçi was arrested in 1958. What were some of the key moments of that period that influenced Demaçi’s development?

Shkëlzen Gashi: There are a few moments from the end of WWII up until the first time he was arrested in 1958 that had a crucial influence on Demaçi’s political formation, but here I will mention three that I consider to be the most important.

The first moment was immediately following the end of WWII, while Demaçi was studying at the eight-year long gymnasium in Prishtina. Yugoslav partisans had dug a hole, known today as “Strelishte,” in which they threw the dead bodies of NDSH [Albanian National Democratic Movement, popular anti-communist insurrection] activists after executing them by gun squad. Demaçi told me about how the sound of these executions often woke him up during nighttime.

A photo of 23-year-old Demaçi, taken from Shkëlzen Gashi’s book “Adem Demaçi, an unauthorized biography.”

The second moment is in 1953, when Yugoslavia’s President Josip Broz Tito signed a gentlemen’s agreement with Turkey’s minister for foreign affairs, Mehmet Köprülü, to ensure the deportation of Albanians from Yugoslavia to Turkey. When I asked Demaçi what moment the most difficult moment in his life, he told me: “the deportation of just about all of my friends to Turkey during the 50s.”

The third moment is in winter 1955-56, when the Yugoslav regime began the campaign of weapon collection in Kosovo. Demaçi spoke about how “people were taken from their homes and mistreated, tied up and dragged in the freezing cold, until their skin fell like feathers from a chicken.

“They looked for weapons. Naturally, you didn’t have a weapon. They forced you to buy one. Fearing that he would have to go through that torture again, a neighbor of mine hung himself.”

Demaçi was first arrested and sentenced in 1958, one year after he published his book “Snakes of blood” and a few other stories in the “Rilindja” newspaper. In his biography, you say that at that time Demaçi was not “a member of any illegal organization… but spoke about everything, everywhere and with everyone.” What risks did Demaçi’s writings present to the regime at the time?

Demaçi was arrested for the first time on November 19, 1958, in the offices of the daily newspaper “Rilindja,” where he worked as editor of world literature. He was arrested on the justification that he had partaken in hostile activity against the state apparatus of Yugoslavia, and that he had been engaged in the struggle for the secession of Kosovo from Yugoslavia and its unification with Albania.

In truth, Demaçi’s open statements and writings against the injustices done against Albanians, as well as the idea that was conveyed by his book, “Snakes of blood,” had incited Yugoslav authorities to arrest him. However, Demaçi was also surprised by his arrest: he asked the policemen who arrested him whether they had the wrong person.

Photo: Atdhe Mulla / K2.0.

During the many conversations that I had with him, he admitted that while he wrote “Snakes of blood,” he never thought that he could get arrested for it, because he didn’t think they were so stupid so as to make the issue even bigger than it was. Later, the book “Snakes of blood” was distributed by students and activists of the illegal movement, often covered by the cover of Serbian author Ivo Andrić’s book titled “The Bridge Above Drina.” In fact, during his time in prison, Demaçi met Albanians who were sentenced simply for reading the book.

Demaçi was one of the first people to publicly criticize the regime at the time. In your perspective, did Demaçi oppose them because he was more intellectually prepared, or was braver than others?

For that time, Demaçi was very intellectually advanced. As a student, he published stories in the “Rilindja” (“Rebirth”) newspaper and magazines such as “Jeta e re” (“New life”) and “Zani i Rinisë” (“Voice of the Youth”), under the special care of his professor Idriz Ajeti and poet Esad Mekuli. Then, from 1953 until 1958, as a student of World Literature at the University of Belgrade and a scholar of the “Rilindja” newspaper, Demaçi became established as a writer of short stories through which he bravely opposed the difficult socio-economic situation, in particular the deportation of Albanians to Turkey.

During his studies, he followed lectures on world literature held by renowned professors in Belgrade and read the works of famous world authors: Balzac, Hemingway, Kafka, Camus, Maupassant, Chekhov, Dostoevsky, Tolstoy, and so on. Demaçi had the two characteristics that, according to philosopher Jean-Paul Sartre, compose an intellectual: knowledge and courage. His courage was motivated by his knowledge.

You say that according to Demaçi, the Revolutionary Movement for the Unification of Albanians (RMUA), which he established, was one of the causes that led to the fall of Aleksandar Ranković, vice president of Yugoslavia. After his fall in 1966, the state started to approve amendments which made the Albanian language an official language beside the Serbian language, and allowed the use of the national flag, and it was also said that they would review the sentences of Albanian political prisoners. According to you, does such a claim stand, and were these demands concretely articulated by Demaçi before he was imprisoned?

I don’t think Demaçi’s claim that the organization that he established and ran — the Revolutionary Movement for the Unification of Albanians — was one of the causes of Aleksandar Ranković’s fall, stands. His fall came as a result of conflicts that he had with TIto.

As for the articulation, the RMUA’s primary and ultimate objective was “to ensure the right of self-determination, until complete secession, for Albanian-majority territories that are under the administration of Yugoslavia.” The program says that “to achieve the above-mentioned objective… the RMUA will take all measures and use all means that it has at its disposal, from political to propagandistic, up to armed warfare and popular uprising.”

...very few people, besides his close friends and relatives, dared to meet Demaçi. In the streets, many people pretended not to know him.

In the late ’60s and early ’70s, the situation in Kosovo changed radically regarding politics, the economy, education, culture and so on, and this change was a result of many factors, but here I will only mention three factors at different levels: at the Kosovar level, it was the demonstrations of 1968, which were organized by the youth of RMUA, an organization established by Adem Demaçi, Ramadan Shala and Mustafa Venhari.

At the Yugoslav level, it was the fall of Yugoslavian internal minister Aleksandar Ranković and the changes that this development brought to Yugoslavia. At a broader level, it was the USSR’s intervention in Czechoslovakia, which influenced an improvement of relations between Yugoslavia and Albania, due to the fear that such an intervention could also happen in these two countries. Consequently, that improvement resulted in an improvement of Kosovo’s position in Yugoslavia.

Beyond Kosovar structures or politicians of the time in former Yugoslavia, what reputation did Demaçi have among the population of Kosovo?

Before he was arrested for the first time in 1958, Demaçi was a man of great reputation: he had published around 20 stories in different newspapers and magazines, stories that were echoed in society; he had published “Snakes of blood,” which was the first novel to be published in Kosovo; he worked as an editor of world literature at the “Rilindja” newspaper.

Naturally, in the first (1961-1964) and second periods between his sentences (1974-1975), very few people, besides his close friends and relatives, dared to meet with Demaçi. In the streets, many people pretended not to know him. Esad Mekuli is an exception. Moreover, the state apparatus prevented him from finding a job, so as to intimidate others.

Demaçi’s opponents, mainly followers of Ibrahim Rugova, objected him for these shifts in political position.

Demaçi was prepared to do any kind of job, even to dig sewer canals, but wherever he sought work, he was refused. At that time, the chances of publishing a book were very slim, therefore Demaçi pretty much didn’t write at all. In the ’80s, and especially after being released from prison in 1990, the situation fundamentally changed and he became one of the most admired personalities among Kosovo Albanians.

What was Demaçi accused of by state authorities at the time?

He served his first prison sentence (1958-1961) after being arrested for his writings, and his second prison sentence (1964-1974) after establishing the Revolutionary Movement for the Unification of Albanians (RMUA). He accepts these two sentences, which amount to a total of almost 14 years, whereas he says that his third prison sentence (1975-1990), which is half of his lifetime total, had no legal basis since he had done absolutely nothing, but it seems that the regime was afraid that he could do something, so they wanted to intimidate others through him. Demaçi was a victim, a man who was made a martyr by Yugoslavian authorities at the time.

Even during the time that Demaçi spent in prison, he was renowned for changing his position. What does this tell us?

Initially, Demaçi was engaged for the secession of Kosovo and other Albanian majority territories in former Yugoslavia, and their unification with Albania. After finishing his second prison sentence in 1974, he considered that political circumstances in Kosovo and Yugoslavia, but also in the world, had changed significantly and that Albanians had to engage to advance Kosovo’s status — from an autonomy to a Republic within the SFRY.

Pas daljes nga burgu në vitin 1990 ai angazhohej për pavarësinë e Kosovës, kurse nga mesi i viteve ’90 për projektin Ballkania, që parashihte një konfederatë në mes Serbisë, Malit të Zi e Kosovës, ndërkaq në vitin 1998, si përfaqësues i përgjithshëm politik i UÇK-së, kthehet sërish te opcioni për Kosovën e pavarur.

A photography taken from the book “Adem Demaçi, an unauthorized biography,” which is believed to be Demaçi’s only photograph taken during his time in prison.

After being released from prison in 1990, he was engaged in the struggle for Kosovar independence, while in the mid-’90s he worked for the Ballkania project, which foresaw a confederation between Serbia, Montenegro and Kosovo, whereas in 1998, as the general political representative of KLA, he again supported the alternative of Kosovo’s independence.

Demaçi’s opponents, mainly followers of Ibrahim Rugova, criticized him for these shifts in political position. However, Ibrahim Rugova was also initially engaged in bringing back Kosovo’s autonomy, which was abolished by Serbia in 1989, and then in making Kosovo into a Republic within Yugoslavia, and then in achieving Kosovo’s independence and sometimes he mentioned the unification of Kosovo with Albania as an option. In the mid-’90s, Rugova proposed to turn Kosovo into a UN protectorate; in 1999 in Rambouillet, he signed for substantial autonomy under Serbia and Yugoslavia and ultimately, after the war, he was again engaged toward the alternative of Kosovo’s independence.

The ultimate objective of both was freedom and independence for Kosovo. The changes in political positions in certain circumstances and periods of time were political strategies to achieve the ultimate objective.

In the ’90s, Demaçi was in conflict with just about all Albanian politicians and intellectuals of the time. What kind of relations did Demaçi have with dominant figures of the public scene at the time?

The main political conflict of the ’90s was between Adem Demaçi and Ibrahim Rugova.

Rugova rejected the idea of active resistance — blocking roads, organizing food strikes, occupying public buildings and similar activities — with the justification that this would be convenient for Serbia, which was hungry for armed action in Kosovo. Rugova’s objective was to evade violent conflict and eliminate the existing prejudice about Albanians being armed and revengeful. Rugova aimed to internationalize the issue of Kosovo through a communication strategy, by informing the democratic world about Serbian repression in Kosovo, so as to achieve a UN protectorate for Kosovo, and ultimately to declare independence.

After the war in Kosovo (1998-99), Demaçi visited just about every settlement of Kosovo minorities and encouraged their members to stay in Kosovo, and simultaneously called on Albanians telling them not to attack minorities and saying that minorities were Kosovo’s fortune.

On the other hand, Demaçi advocated a more active resistance. He proposed to occupy buildings and institutions of the Serbian regime, as well as main streets and squares and to stay there for days and nights on end, until Serbian police forces would come.

Demaçi insisted that “maybe Serbia would kill another 20,000 citizens because Serbia is for real, but we have to show Serbia and the international community that we are for real too,” because “Serbia does not abandon its occupation of our institutions without covering them in blood.” In the mid-’90s, Demaçi described the peaceful passive resistance, led by Rugova, as a decoration that served the Serbian state apparatus to prove to the international community that a democratic system was functioning here.

When Demaçi was released from prison in 1990, although he suffered a lot from the ethnic division that existed in former Yugoslavia, he continuously insisted on making a distinction between Serbian statesmen and Serbian people. What does this tell us?

If there is one thing about Demaçi that fascinates, it is particularly this distinction that he makes between the Serbian people and the Serbian political class. Although aware of the terror that was being committed against Albanians, in public appearances he often used phrases such as “our brothers, the Serbian people” or “the heroic Serbian people,” because he believed that the Serbian people were manipulated by the people in power, and was against generalizations that equated all Serbs to the political class that was in power.

Demaçi expressed these positions publicly because he wanted to halt efforts of revenge, and because he believed that this best contributed to Kosovo’s interests. Moreover, he believed in human rights and he was therefore adopted as a “prisoner of conscience” by prestigious human rights organization Amnesty International and won, among others, three prestigious international awards: the Sakharov Prize for Freedom of Thought that was given by the European Parliament, the Special Prize for Peace against Racism and Xenophobia that was given by the Club of University Rectors in Madrid and the Leo Eitinger Prize for Human Rights that was given by Oslo University.

After the end of the war in Kosovo, Demaçi criticized Albanians for their treatment of minorities, especially highlighting the killings of Serbs. Later on, he called on Serbs to take risks for their freedom of movement, taking himself as an example when in 1998-99 he didn’t accept a life of evading Prishtina’s streets, although his life was at risk. Can we draw parallels between developments at the time and today?

After the war in Kosovo (1998-99), Demaçi visited just about every settlement of Kosovar minorities and encouraged their members to stay in Kosovo, while simultaneously calling on Albanians to not attack minorities and stating that minorities were Kosovo’s fortune. Had his suggestions been realized, the situation regarding the Serbian minority in Kosovo, and consequently the overall situation in Kosovo, would be completely different, and we would have no negotiations for a Republika Srpska in Kosovo, nor would we have a Specialist Court.

In the last years of his life, it seemed that Demaçi became close to certain PDK political figures and seemingly surrendered to party pressure. Did such a thing happen? How do you see this?

Demaçi’s affinity with Thaçi’s regime started in February 17, 2008, when he partook in the session in which independence was declared; arrangements were made so that the Office of the Prime Minister of Kosovo provided Demaçi with a national pension, a government vehicle and a driver; the house that had functioned as the office of the KLA in Prishtina was declared a museum.

For me, it is saddening to see a man who opposed Tito’s regime for 30 years, then opposed Milošević’s regime for 10 years and then opposed the international community for 10 years in Kosovo, to ultimately, at a very old age, be transformed into Hashim Thaçi’s tool, which he used whenever he needed the TV channels he controlled to speak in favor of his regime. All this says more about Hashim Thaçi than about Adem Demaçi.

Shkëlzen Gashi, author of “Adem Demaçi, an unauthorized biography.” Photo: Atdhe Mulla / K2.0.

Ten years ago, you published an unauthorized biography of Adem Demaçi. What happened?

When I started writing the biography in 2008, Demaçi accepted to be interviewed on the condition that before publishing, he would read the book and correct eventual inaccuracies, and that the biography would be published with his authorization. He read the text before it was published and provided some very helpful remarks, for which I am very grateful. However, when I submitted the final version of the biography, he arbitrarily demanded that I remove certain parts. Demaçi wanted to “correct” truths that he disliked, and I didn’t accept.

He demanded that I remove a few paragraphs that together constituted no more than 4-5 pages of the book, in which I mainly mentioned PDK figures. I didn’t accept to remove them for a simple reason: none of the statements were fiction, and they were all documentable. Despite whatever reason that pushed Demaçi to insist on removing the above-mentioned moments, I followed one of his virtues, one that I always admired and which was my main motive for writing this biography: the determination not to recede when faced with the pressure of censorship, however tenacious it may be, even when it comes from Adem Demaçi.

Ultimately, is Adem Demaçi real or a myth?

Adem Demaçi has been mythologized, but only by a very small group of citizens… His life and activism bust be studied and we must not allow the creation of a myth. It seems that, concerning the myths of personalities of contemporary Kosovar history, the most powerful are the myths of Ibrahim Rugova and Adem Jashari, which we must deconstruct as soon as possible.K

Feature image: Kushtrim Tërnava / K2.0.