When Blerta* was accepted at the University of Prishtina in 2014, she felt it was necessary to find a job so that she could make a living. In Podujevë, her hometown, one of the supermarkets had published a job call for an ‘arkëtare’ (the feminine form of the word for cashier). The gender-specific language encouraged Blerta to apply for the job, which she continues to work to this day.

She is not the only one with such “luck.” There are many supermarkets and shopping malls that advertise employment opportunities with the idea of “work for men and work for women.”

Positions such as department manager, cashier, janitor, promotional staff or general assistant are announced with feminine gendered terms in many job calls. With positions such as warehouse manager, waiter, manager, hall manager or senior manager, masculine forms of the word tend to be used.

In the supermarket in which Blerta works, she is not the only woman cashier; all four of the cashiers that work across two shifts are women.

Besa* also works as a cashier in a supermarket in Prishtina. A couple of years ago, the 22 year old applied to a job call which sought a department manager. She worked there for one year before being moved to a position as a cashier, where she currently works and receives a wage of 250 euros.

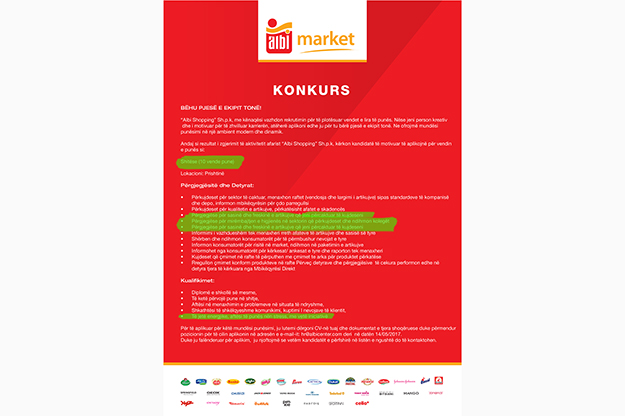

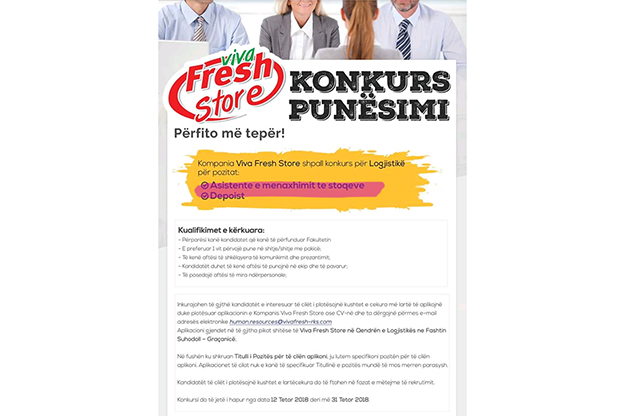

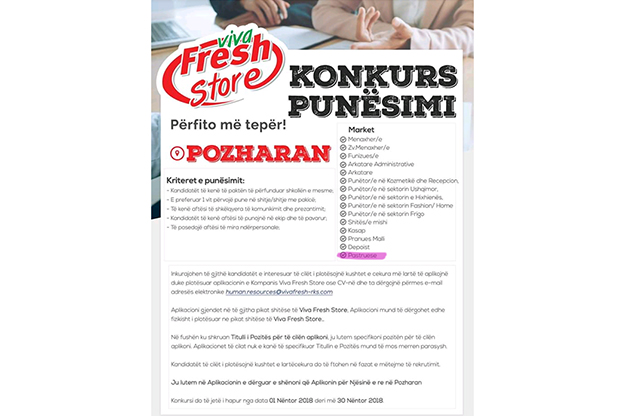

These differences in positions, which are reflected through the language used in job calls have been notable for many years. Between October 22 and November 4, Viva Fresh Store opened a job call for the position of “Administrative Assistant/Translator (in the female form) for the Office of the Executive Director.”

On November 10, the same company sought to employ an “assistant stock manager (again in the female form),” as well as a “warehouse manager (in the male form).” In a job call published by a Viva Fresh Store in Pozheran, Viti, through the language used it was stated that the person who was to be employed to maintain hygiene in the store had to be female — “pastruese.” On the same date, Albi Market, which has multiple supermarkets in Prishtina, published a job call for 10 salespersons, again using the feminine form of the word.

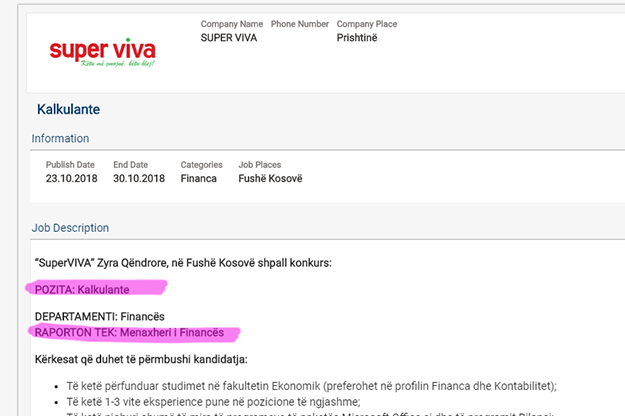

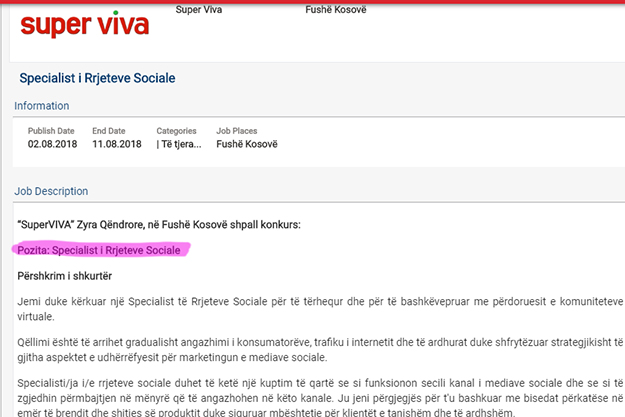

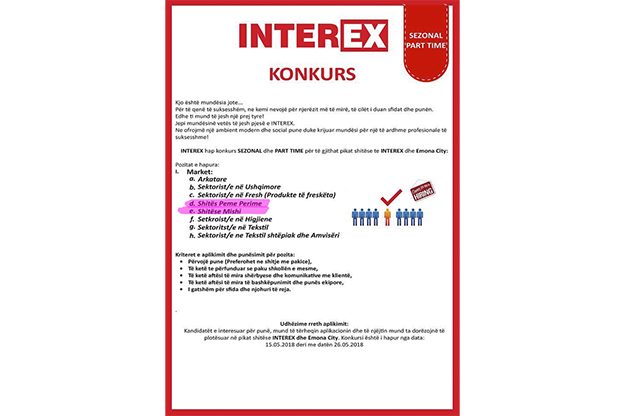

Konkurset e punës nga disa supermarkete.

Konkurset e punës nga disa supermarkete.

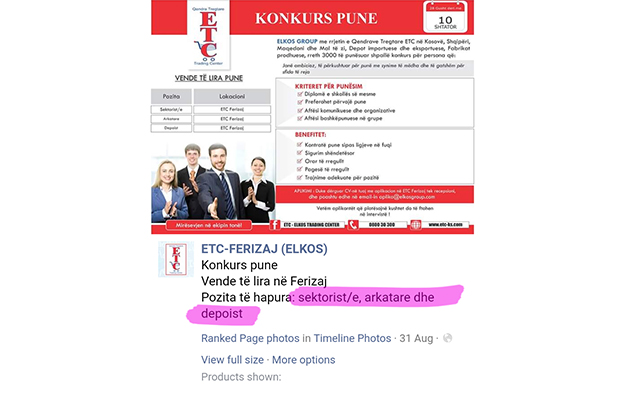

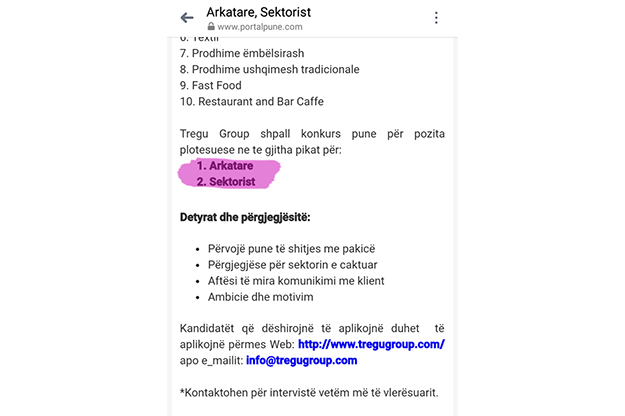

Elkos Group, which leads the network of ETC shopping centers, planned to prepare for the past summer by hiring seasonal workers for its branches in 22 cities. In April, the company, which is owned by deputy in the Kosovo Assembly, Ramiz Kelmendi, advertised the position of department manager as one for which they were open to employing people of both genders, whereas, judging by the language used, cashiers had to be women, and warehouse managers had to be men.

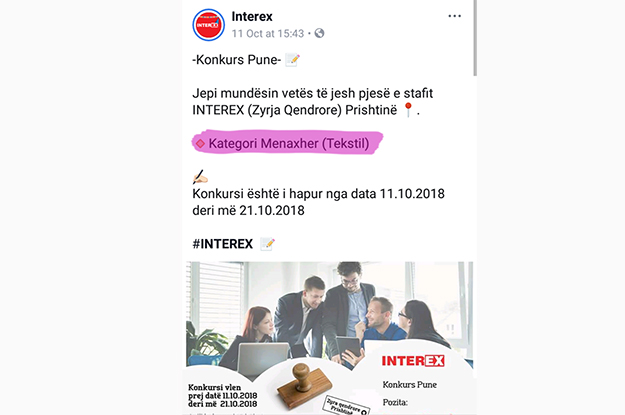

The Interex chain of supermarkets also follows this example. In Spring they published a job call in which they made distinctions about who could sell what: for selling fruits and vegetables they sought a male shop assistant, whereas for selling meat they sought a female shop assistant.

These chains have branches in many cities. Super Viva has at least one supermarket in each of the 7 biggest cities in the country. A couple of months ago, the company sought to employ a female accountant in its finance department, one who would report to the male finance manager. Meanwhile, in its branch in Fushë Kosovë, they sought to employ a male social media specialist.

The language used in these job calls has continuously been considered as discriminatory, a barrier to the employment of women and as a factor which influences gender inequality. It continues to be used despite the fact that in at least four of Kosovo’s laws — the Labor Law, the Law against Discrimination, the Law for Civil Service and the Law for Gender Equality — any form of discrimination in access to work is prohibited.

To discuss job calls and other issues, K2.0 contacted all of the aforementioned companies by email and phone, but they did not respond.

The effects of gendered job calls

Kosovo continues to face a difficult economic situation, while the level of unemployment stands at 30 percent. Young people and women are the groups most susceptible to unemployment; a Labor Force Survey conducted by the Kosovo Agency of Statistics in the second quarter of 2018 showed an employment rate of only 12 percent among women.

In May 2017, the Gap Institute released a report on “Discrimination in the labor market.” In it, they highlighted that in addition to the high level of unemployment and ‘family engagements of women,’ another reason for the low level of employment among women are “job calls with discriminatory language.”

As part of the report, they conducted an experiment through Facebook, where they published two job calls. The first job call sought to employ ‘five interns’ (using the feminine form of the word), whereas the second sought ‘five interns’ (with the masculine form of the word).

Sixty-nine percent of those who saw the first posting were women, whereas 31 percent were men. This came mainly as a result of women being tagged on social media. For that job call, from the CVs that were received, only 11 percent were from men. In the second posting, which used the masculine form of the word, over 79 percent of people who saw it were men, again mainly as a result of being tagged by their friends.

However, despite more men seeing the second job call, from the 42 received applications, 43 percent were from men, while the rest, 57 percent, were from women. According to the report, one of the reasons for this could be that women are used to discriminatory job calls, and such language in job calls can be perceived as standard or something normal.

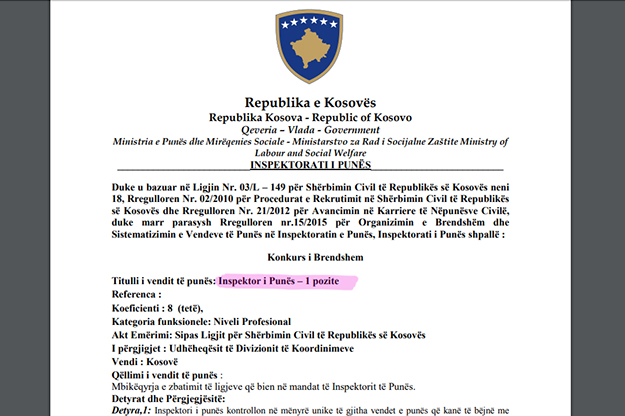

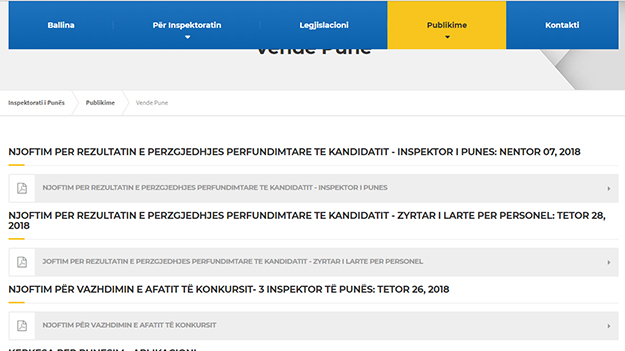

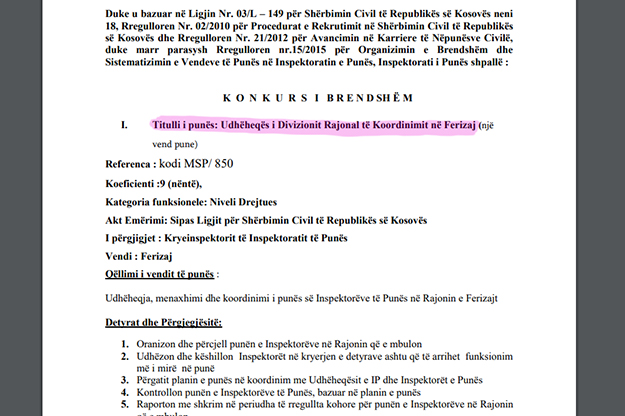

Job calls published by the Labor Inspectorate containing gender-based discriminatory language.

Job calls published by the Labor Inspectorate containing gender-based discriminatory language.

Amazingly, it seems that even the Labor Inspectorate (LI) functions with this standard. This institution is supposed to protect the Labor Law, which determines that job calls must be equal for all.

On October 5 this year, the LI published an internal job call for the position of “Labor Inspector (using the masculine form).” In the description of duties and responsibilities, in point 1 it is stated that “The inspector (masculine form) has a duty to…”, and goes on to further describe the position with language that implies that the position will be occupied by a man.

Three days before the end of 2016, the LI opened a job call in Ferizaj for the position of “Director (masculine form) of the Regional Division for Coordination.” K2.0 contacted the Ministry of Labor and Social Welfare and the Labor Inspectorate to ask about this, but received no response.

KIPRED researcher Ariana Qosaj-Mustafa believes that both these job calls are“direct” violations of the Law for Protection Against Discrimination, in which it is clearly stated that job calls must be equal for all, and contain no discrimination. She is surprised that the institution that should protect laws and fight discrimination are doing the opposite. According to her, these job calls “can be penalized in formal legal procedures.”

The limitation of 50 percent of the population to only certain professions has effects on the economy.

However, this approach doesn’t surprise Luljeta Demolli, the Director of the Kosovar Center for Gender Studies at all. For her, for quite some time the state has discriminated against women in their fundamental rights, including the right to work. “Women are also discriminated against in employments by the [political] parties. Usually the man of the house gets the job so that the whole family votes for the party,” she says.

For Demolli, discrimination in employment brings many social and economic implications. “This maintains gender stereotypes”, she says, going further to highlight that the employment of women and the freedom to choose professions would be a step towards change, making women independent.

She sees such an approach by institutions and businesses as “a tendency to bring the role that women have at home — as someone who serves, cares and cleans — to the workplace.” To argue this, Demolli highlights the professions in which, according to her, women are pushed to contribute to the labor market: cleaners, saleswomen, members of the banking sector, the administration sector, the education sector and the healthcare sector.

According to Qosaj-Mustafa, the limitation of 50 percent of the population to only certain professions has effects on the economy. Changing this would not only bring improvements to the situation of women in the social aspect, but also to the general economic situation in the country. “Experiences of multiple European Union states and International Monetary Fund reports show that equal inclusion [of the two genders] in the labor market creates economic growth,” she says, arguing that equal inclusion grows competition and contributes more to the free market, creating more opportunities.

Photo: Atdhe Mulla / K2.0.

Iliriana Banjska from the Kosovo Women’s Network (KWN) highlights that “the idea that women and men differ in their professional skills creates this situation.” For her, this is not a cultural influence of the Kosovar society, but comes from global developments.

As part of a report that KWN compiled in 2016, they conducted surveys with employers asking them whether the job they offered was ‘more suited for men,’ ‘more suited for women,’ ‘suited for women and men’ or ‘depends on the position.’ Forty-seven percent of them answered that the work was more suited for men, while 35 percent said it was suited for both men and women.

Demolli believes that state institutions have the right to undertake “affirmative measures to change the situation of a certain social group”, and should do so, as this directly influences the unemployment of women. For her, a lack of action implies that institutions are OK with this situation.

But the state is not doing well in its own backyard either. Around 95 percent of senior management positions in the Government, the Assembly and the Presidency are dominated by men, a statistic reported by the GAP Institute in May 2017.

Deception

There are at least nine big companies which have extended supermarket chains throughout Kosovo, with millions of euros circulating through them each year. Thousands of employees contribute to this capital, while these businesses were boosted by the country’s economic reliance on trade, as is highlighted every three months in reports published by the Kosovo Statistics Agency, with trade routinely being shown as the most profitable sector.

The Ministry of Trade and Industry (MTI) provided K2.0 with data which show that over 12,000 businesses with over 17,000 employees are active and oriented towards retail trade, making profit from selling “food, drinks and cigarettes.” Supermarkets are included in this sector.

Although the MTI has no specific data, the majority of employees in this sector are believed to work in supermarkets. According to deputy Kelmendi, his company alone employs 3,000 people. It is also believed that the number of employees in supermarkets is bigger than the one stated in MTI’s figures due to the informality that characterizes the Kosovar economy.

Last year, the Union of Independent Syndicates estimated that 50 percent of employees in the private sector work without contracts, a finding that was opposed by the chief labor inspector, who believed that it is in fact around 10-12 percent. The Alliance of Kosovar Businesses says that the number of employees who work without contracts reaches 20 percent.

“They employ women because they pay them less.”

Luljeta Demolli, Director of the Kosovar Center for Gender Studies

Tesa from Prizren is an element in this percentage, whichever is the correct one. From June until August 2018, she worked as a department manager and warehouse manager in one of the supermarkets in her hometown. Up until the end of June, she worked as an unpaid intern, then as a regular employee, but was still not offered a contract.

She is not the only one. A July 2017 report by Center for Investigative Journalism Preportr showed that there were many employees who work without contracts in supermarkets. Chief Labor Inspector Basri Ibrahimi was asked about inspections in supermarkets and their findings. However, he did not provide data, saying “we do not divide data based on sectors, except for findings in the construction sector.”

Nevertheless, while unemployment remains high, with or without contracts, employment tends to be seen as something good that supermarkets bring to society, especially the employment of women.

But Demolli doesn’t believe this. “Supermarkets would be very happy if we were to tell them that they are employing these women only because they are women,” she says. There she sees a form of deception used by supermarket owners with the objective of profiteering. “They employ women because they pay them less”, she says.

She backs this claim with data from conversations with women who work in supermarkets. From her research, she estimated that their wages are on average 190 euros per month. According to the employees, just about every month they are fined 20 euros.

Iliriana Banjska from the Kosovo Women’s Network believes that women are paid less across the Kosovar economy, but says that there are no specific statistics in this regard. She uses the sectors where they work as an argument. “We know that women are employed more in sectors in which wages are lower than in male-dominated sectors”.

In 2017, the Riinvest Institute published the report titled “Women in the labor market.” In a survey which used a sample of 600 employed women, the main stated issue in the workplace (36 percent) was “low wages.”

Demolli insists that the dire economic situation of women and gender stereotypes which are prevalent in Kosovar society is another advantage for the supermarkets. These factors create an environment in which there is more pressure on, and exploitation of, women, which consequently leads to violations of rights which are guaranteed by the labor law.

For Demolli, “calls for employing women are a disguise”.

Besarta** also says that women who work in supermarkets are treated differently and are continuously pressured. For three years she has worked in a supermarket in Prishtina, but has recently resigned.

Another deceptive criteria for employment which is used by private businesses is the marital status of women.

For the 25 year old, even the smallest mistake in her work would be followed by words like “ah, women.” According to her, such an approach is also displayed by customers. To explain how hard it is to work in these environments, she makes a comparison with women who work in senior positions in the public sector. “Even for them they say ‘they don’t know anything’, let alone for lower level work – they have no respect at all.”

Besarta*, who is now looking for a job, recalls moments of “direct or indirect” harassment by employers or customers. “Women are not spared at any moment,” she says.

Age is also a factor. Job calls with age criteria are notable in Kosovo, usually seeking people between 18-35 years of age. Demolli highlights that supermarkets also implement such policies. “It is painful because you rarely see elderly women working there”, she says. But recently, according to her, this has started to change, with more older women being employed, but still with ulterior motives.

For her, another deceptive criteria for employment which is used by private businesses is the marital status of women. “Maybe they do not put it in the job call, but in interviews they ask how many family members you have or whether you are married or not,” going on to say that this is done with the purpose of evading maternity leave.

While supermarkets may have added employment opportunities for women in Kosovo, the attitudes towards and conditions for workers and gendered language used in job calls are seemingly doing little for equality for either women or workers.K

*At the request of the people interviewed, the names of some supermarket employees have been changed, due to fears over losing their current jobs and insecurities around finding another one.

Feature image: Atdhe Mulla / K2.0.

This article was produced by Kosovo 2.0 as part of the Equal Rights for All which is an EU funded project managed by the European Union Office in Kosovo.

The contents of this publication are the sole responsibility of the project and can in no way be taken to reflect the views of the European Union.