Imagine you are just waking up from anesthesia after surgery. You open your eyes in a state of confusion and you start taking in your surroundings. What are the first things you see, and how do they make you feel?

Does a cool, unfeeling light bulb hang clinically from a low ceiling, so bright that it burns your eyes, adding to the disorientation and perhaps making you feel anxious? Or maybe you find yourself in a spacey, naturally lit room with subtle wood detailing on the walls, as the shadow of a tree’s branches sways to the rhythm of the breeze outside.

Soon enough a caretaker’s face might enter your field of vision and the physical symptoms you might be having will turn your attention inwards — nevertheless the way you experience those initial moments of coming round has a role to play in your recovery.

Knowing this, don’t you wish that someone was laying the groundwork that in the future might inform those in charge wanting to make similar experiences as comfortable as possible? Rest assured (pun unintended), someone is on it, or will be soon enough.

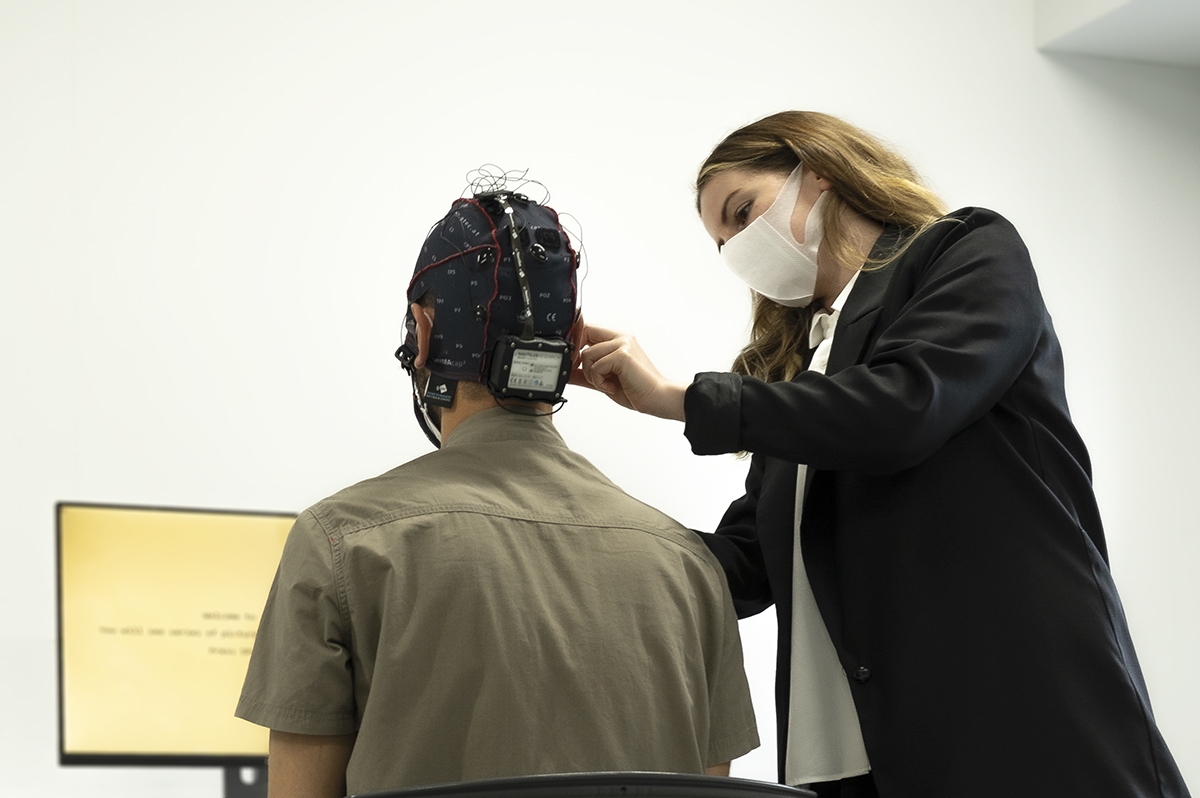

Dea Luma is one of the world’s leading neuroarchitects and is currently heading up a brand new neuroarchitecture lab at the University of Tokyo, Japan. Photo courtesy of Dea Luma.

Dea Luma, a Prishtina-raised scientist in her early 30s, is the person entrusted with establishing the University of Tokyo’s neuroarchitecture laboratory, a multidisciplinary area of research focusing on the brain and the human experience of architecture. Given that we spend most of our time indoors, the newly-established lab is set to find out ways in which architectural design impacts us, its users.

Luma was the first person to complete PhD studies in Neuroarchitecture at the prestigious University of Tokyo’s Department of Architecture, and the university found her pioneering work compelling enough to establish a whole new paradigm in architecture, one that focuses on the wellbeing of users and promotes evidence-based design to that end.

The assistant professor now spends a good part of her days designing and conducting experiments in her lab, surrounded by research subjects wearing futuristic-looking headsets that measure their brain waves as they sit in front of screens showing different architectural design characteristics. At other times she can be found teaching the university’s first neuroarchitecture master’s class, or exchanging specialized knowledge with fellow scientists.

The brains behind fresh design

Part of Luma’s practical experience came through a period working at the Center for Advanced Intelligence at the renowned Japanese research institute RIKEN, where she studied the impact of architectural design on Alzheimer’s patients through brain wave measurements.

“If you put an Alzheimer’s patient in an environment that is a copy-paste of the environment where they grew up, it has been proven there’s a likelihood that some neurons will fire and some lost memories will be recreated,” she says, describing an aspect of Reminiscence Therapy, which uses the senses to help patients with cognitive diseases to revisit moments from their past.

Another way is through music, as shown in a viral video of a former ballerina with Alzheimer’s who starts to dance when listening to music from Swan Lake.

Although Luma is quick to explain that this is just one element of neuroarchitecture studies and that in general she conducts research in other types of premises that are not necessarily related to medicine, she acknowledges that to others, this portion might be the most interesting or with the most perceived potential.

“A tendency that I notice when I talk about this topic is that I’m always asked about hospitals because they are a very sensitive point where the experience of the patient is very important,” she says, recalling inquiries from lay people in public events and from other professionals. “[It’s] ‘How can we apply this in the hospital?’ ‘How can we improve the user experience in post-op?’ And, ‘How can that environment be healing for a patient and for those waiting long hours in the waiting room?’”

Such considerations are not necessarily new, with various architectural movements over time having made efforts to adapt architectural design to users’ needs. An epitome of this in terms of medicine dates back to the early 20th century, when architects began designing health facilities — such as the Paimio Sanatorium in Finland — that would themselves function as a medical instrument at a time when tuberculosis was raging. The choices of light sources, color schemes, heating and other design elements were all purposefully curated to foster recovery.

“Although there have been many stages where hospitals have been researched in particular, there were moments when some things were left aside,” Luma says, pointing out that the big development brought by neuroarchitecture is the scientific, evidence-based approach.

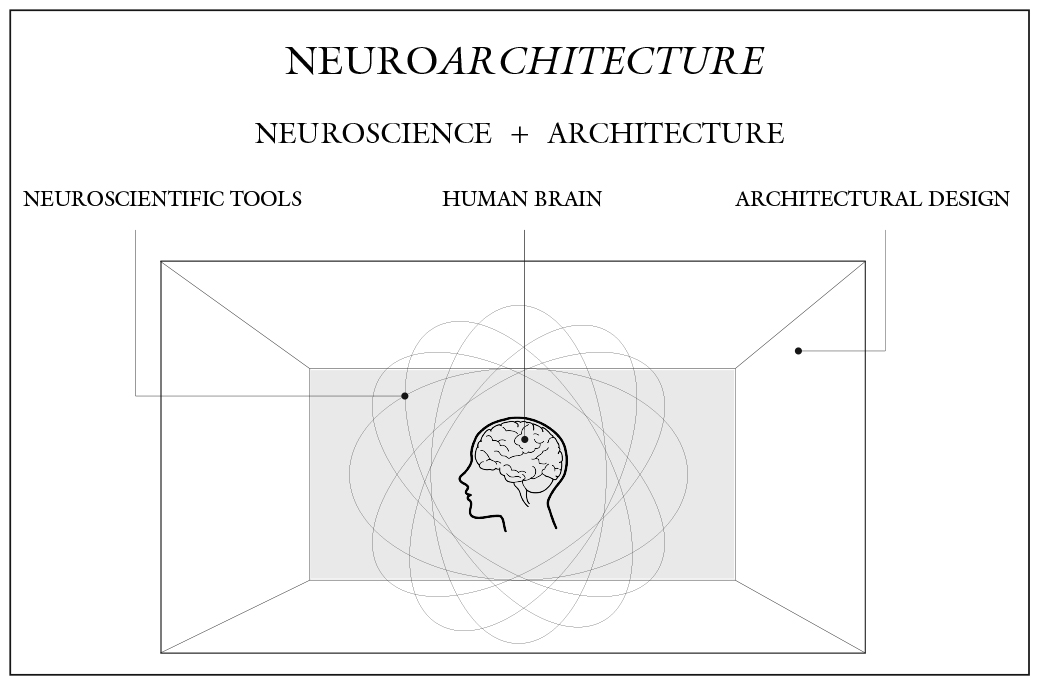

The relatively new field of neuroarchitecture has introduced a more scientific approach to long-established elements of architecture. Image courtesy of Dea Luma.

Naturally the flow of the conversation turns toward the potential implications of COVID-19 as the current era’s pressing health issue.

Luma mentions ongoing discussions in the architecture community about certain architectural characteristics that might be necessary to let go of, and others that might be picked up or adapted post-pandemic. These involve practical considerations such as how to design collective spaces with improved ventilation and features that enable physical distancing when required, as well as psychological considerations such as creating indoor spaces that make people feel safe.

However, she’s adamant that long-term solutions are required to improve indoor environments regardless of COVID-19.

“It’s important — with or without COVID — to understand the impact of indoor environments on us; then [the results] will provide solutions to issues like COVID and to others that we might not know about yet.”

From Kosovo to Tokyo

A considerable chunk of the potential Luma is fulfilling today is homegrown in one of Prishtina’s central neighborhoods.

As a young girl she spent her summer days divided between playing outside with friends, reading, drawing and practicing her chosen instrument of violin. In the winters she remembers sledding in the hilly streets of the city with makeshift sleds and skis “and whatnot.”

As she was growing up in the ’90s, Luma was encouraged by her family to take part in a wide range of activities as well as pursuing her education. Photo courtesy of Dea Luma’s personal archive.

Despite the wider sense of insecurity during the ’90s apartheid imposed by the Serbian regime in Kosovo, she describes her childhood as largely carefree, in the safe haven of a family that nurtured her dedication to learning, while encouraging her to explore a plethora of other activities.

“For my parents it was always very important to plant a book culture and early childhood education, so when this happened for me I certainly was not aware but definitely it has been reflected since then,” she says. “The more you touch on different things, the more you understand what you like; and as a child you might not know how to make those choices but if parents are supportive or push you to do them, it’s always a great help.”

After completing school, Luma decided to study architecture at the University of Prishtina (UP). During her studies she dipped her feet in various streams of architecture and design, but didn’t yet know what she wanted to pursue further. “[At first] I liked archeology, then I started to have so much interest in cultural heritage that my bachelor’s thesis was a combination of both,” she says.

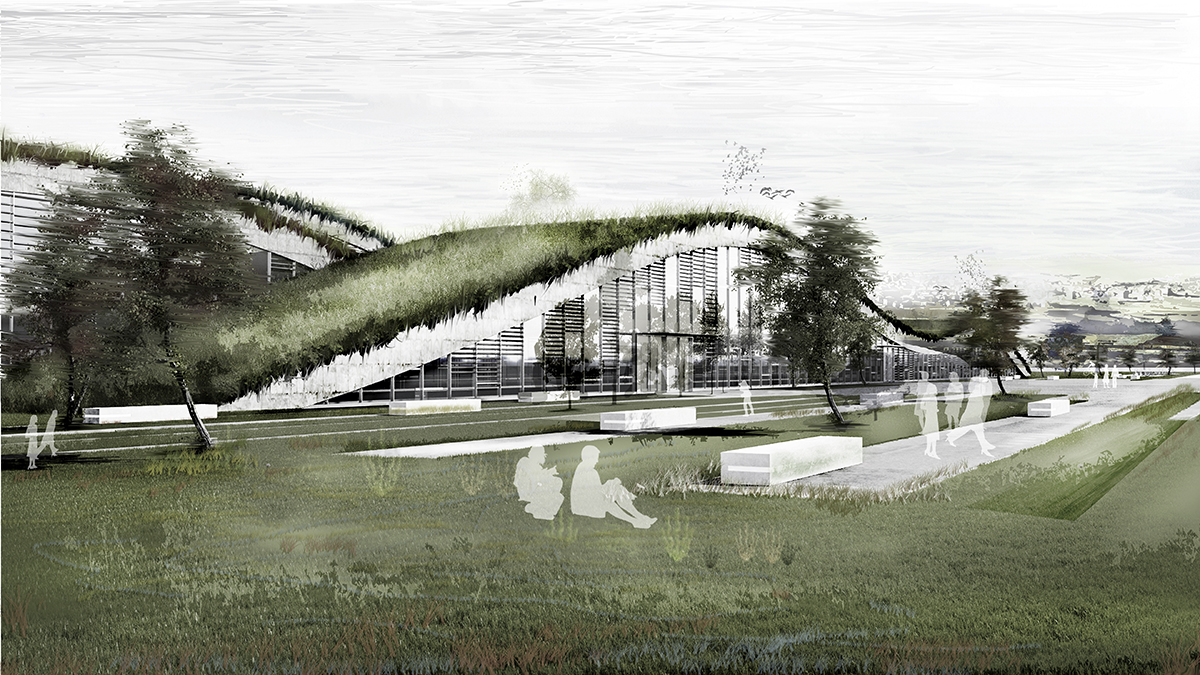

Having completed part of her senior bachelor’s year in Poland, Luma was inspired by Krakow’s underground square central museum and for her thesis she designed a museum for the archeological site of Ulpiana, where the ruins of the 2000-year-old city lie in a meadow not far from Prishtina.

Although not yet knowing what her future path in architecture would be, her early work already hinted that whatever it was, it wouldn’t be showy.

“The proposal was so discreet that you couldn’t notice that there was architecture in such a clean environment,” she says, explaining how she worked the design of her building subtly into its natural surroundings. “[Since only a fraction of the site has been unearthed] at the ancient Ulpiana, I liked the tranquility of the field so much that I kept it.”

As part of her undergraduate thesis at the University of Prishtina, Luma designed a fresh proposal for the ancient Ulpiana archaeological site outside of Prishtina. Image courtesy of Dea Luma.

While her Ulpiana proposal — like the majority of projects conducted by architecture students at UP — remained just that, she did end up working at the Kosovo Archeological Institute for a time, alongside studying for her master’s at UP.

As her experience grew, so did her opportunities. “I wanted to finish my master’s in order to obtain my practicing licence, but in the meantime I was looking at where, how, and it was during this time that I applied for the Japanese government scholarship,” she recalls.

When she learnt that her scholarship application had been successful at the beginning of 2016, she knew an executive decision had to be made: whether to begin practicing after securing her upcoming license or whether to pursue a doctorate. “I decided on a doctorate — I don’t know what the moment was, but maybe because I was always excited to specialize in one field and to be an expert in something rather than a [Jane-of-all-trades],” she says.

So she packed her bags and headed to Japan where she got to work, studying up to 15-16 hours a day for months to prepare for the entrance exam at the University of Tokyo, the country’s leading university and one of the top educational establishments in the world. The scholarship awarded by the Japanese government to international students consists of financial coverage, but prospective grantees must undergo the same tests as Japanese students to enter university, and with no priority.

“If you are not admitted, you have to go back,” she says. “And here, students prepare extraordinarily well for entrance exams, they start preparing in high school; every week they have certain [targeted] classes. For foreign students it is really difficult, that’s why there aren’t many — plus for Kosovo they award one scholarship each year, so it’s competitive.”

An academic liberation

All of Luma’s hard work to this point paid off and in 2017 she began her PhD. Once in, she needed to develop and focus her research ideas into a well-defined topic to explore academically in the upcoming years.

“At first I was mainly interested in the human body, but at that moment I didn’t have an idea of how to make the connection [with architecture],” she recalls. “Then for a period of time I was interested in toxicology. There’s a condition called Sick Building Syndrome — some people get sick when they’re in some indoor environments, and there’s a specific field that studies it.”

Knowing this much about her research interests, her supervisor suggested a meeting with a team of doctors at the university’s department of medicine. The brainstorming discussions slowly led to the idea that the emerging field of neuroarchitecture could offer an avenue to study the human body’s reaction to architecture with the methods and technology that are commonly utilized in neuroscience.

Thinking back to her formative years, Luma says that medicine and architecture had been head-to-head in the contest for becoming her chosen field of study. “I found a way to bring them together,” she says, triumphantly.

The sort of cooperation with colleagues across disciplines that led to narrowing down her research focus in her first year in Tokyo has been a constant throughout all subsequent stages of her work, providing much-needed impetus to persist in an innovative field while lacking virtually any kind of reference.

“No matter which department you belong to, you can take classes in the whole university — whatever helps your research,” she says. “It’s a completely open environment and you can knock on the door of any laboratory.”

Sa e kam shijuar kete artikull! Fameinderit Tring'!

This is a great article

Wow ! I am passionate about both architecture and neuroscience. This article made me discovery that there is a field that links both. Thank you for covering this topic ! My best wishes to the author and to Dea Luma.

Really good article and enjoyed reading it. I hope to read more like this in the future. Best regards and lot of success to Dea.

Tringe, Congratulations on an interesting, well written article. I am so impressed with your education. It has been a while since I knew you when you were going to school here in Illinois. I admire you so much. So proud of you. Take care and please stay in touch. Clara (aunt of the Romano family).