Every summer thousands of members of Kosovo’s diaspora return home to visit their families and every year they send back millions of euros that fuel domestic consumption. For decades, and especially for the last 20 years, these remittances have constituted a lifeline for many families.

Despite the diaspora’s significance for the country, obtaining an accurate figure for its size is not an easy task. The Agency of Statistics conducted its last study on the issue back in 2014, finding that more than 380,000 Kosovars were living abroad, more than one fifth of the country’s population. The Agency itself admitted that the figure was likely an underestimate.

In the years since, Kosovo underwent a massive exodus toward EU countries. Between 2014 and 2015 tens of thousands left. Some returned (or were returned), but others managed to stay and settle. As a result, some have proposed that the number nowadays could be closer to a million.

A community of this size can be critical for the country’s economy; according to the Central Bank, remittances are often three times greater than foreign direct investment (FDI). Even in 2020, the year of the pandemic, that ratio remained stable, with 980 million euros in remittances compared to 342 million in FDI. These numbers do not take into consideration the fact that much of Kosovo’s FDI originates from the diaspora.

The economic struggles of the pandemic in 2020 were compounded by the fact that travel restrictions prevented most diaspora from visiting home. But once they returned in droves in 2021, they came with an influx of 630 million euros in direct spending alone. In this context, it makes sense that keeping the diaspora close is often high on the government’s agenda.

Easing travel

One way the government has tried to facilitate diaspora spending and remittances is by making it easier to travel to Kosovo. One of the most commonly cited annoyances that diaspora travelers face is the issue of car insurance. Thousands of emigrants return by car every year.

The problem is relatively straightforward. International car insurance in Europe is based on the Green Card, a document issued in accordance with standards set by the Council of Bureaux (CoB). With a Green Card, car insurance from any of the Council’s member states is valid in all of them, so travelers remain insured when abroad.

Since Kosovo is not a member of this international organization, foreign insurance is not valid in its territory, and conversely, Kosovar car insurance is only valid in a few neighboring countries. As a result, travelers entering Kosovo must purchase car insurance when they enter the country — a short-term third-party liability policy — a moderate extra expense of around 20 euros, but one that can cause substantial delays at the border.

Although Vetëvendosje (VV) set joining the Green Card as a priority in its previous term in government, that ambition ultimately remains outside of its control since it requires approval from the other member countries, some of which do not recognize Kosovo. Another issue is that as many as 30% of cars in Kosovo are unregistered. This number would have to decrease to 5% before Kosovo could be seriously considered by the CoB.

In the meanwhile, the government laid out 5 million euros from the Covid-19 Economy Recovery Package to support the diaspora and since July 1, border insurance is paid for directly by the state from this package. Travelers, including foreigners who aren’t diaspora, simply receive the document at the border with no extra expense. By the end of the summer government expenditure on subsidizing car insurance for foreign cars reached 2.4 million euros.

It is noteworthy that VV — a party that claims the mantle of progressive social democracy — has promoted this regressive policy.

A recent report by GAP Institute on the policy is critical of this policy. They argue the program should be replaced by an online pre-payment option until Green Card membership has been secured. Most diaspora members are relatively well-off compared to people living in Kosovo. Any direct budgetary transfer to them means that local taxpayers, usually poorer, are subsidizing the better-off diaspora, a textbook case of regressive policy.

This is particularly noteworthy given that VV — a party that claims the mantle of progressive social democracy — has pushed for this measure despite strong opposition from civil society and trade unions.

A possible factor contributing to VV’s support for this decision is the strong approval they have among the diaspora. For example, in the February 2021 elections VV won approximately 75% of the votes from abroad. With so much support going to a single party, the debate around electoral reform has become intrinsically partisan.

Electoral hurdles

Kosovo does not have a separate district for diaspora voters, so they vote wherever they were registered when they lived in the country. In addition, there is no mandatory consular registration, so the electoral roll does not make any distinction between residents and citizens abroad.

When emigrants want to vote, they must apply at the Central Election Commission (KQZ). However, the process wasn’t designed to handle large numbers of requests and it is highly bureaucratized and complicated.

Germin, an NGO created to connect diaspora with the home country, has done oversight research on successive elections, highlighting the deficiencies of the current system. The organization has called for amending the legal framework to facilitate out-of-country voting and proposes alternatives such as refining the current mail system or even full e-voting.

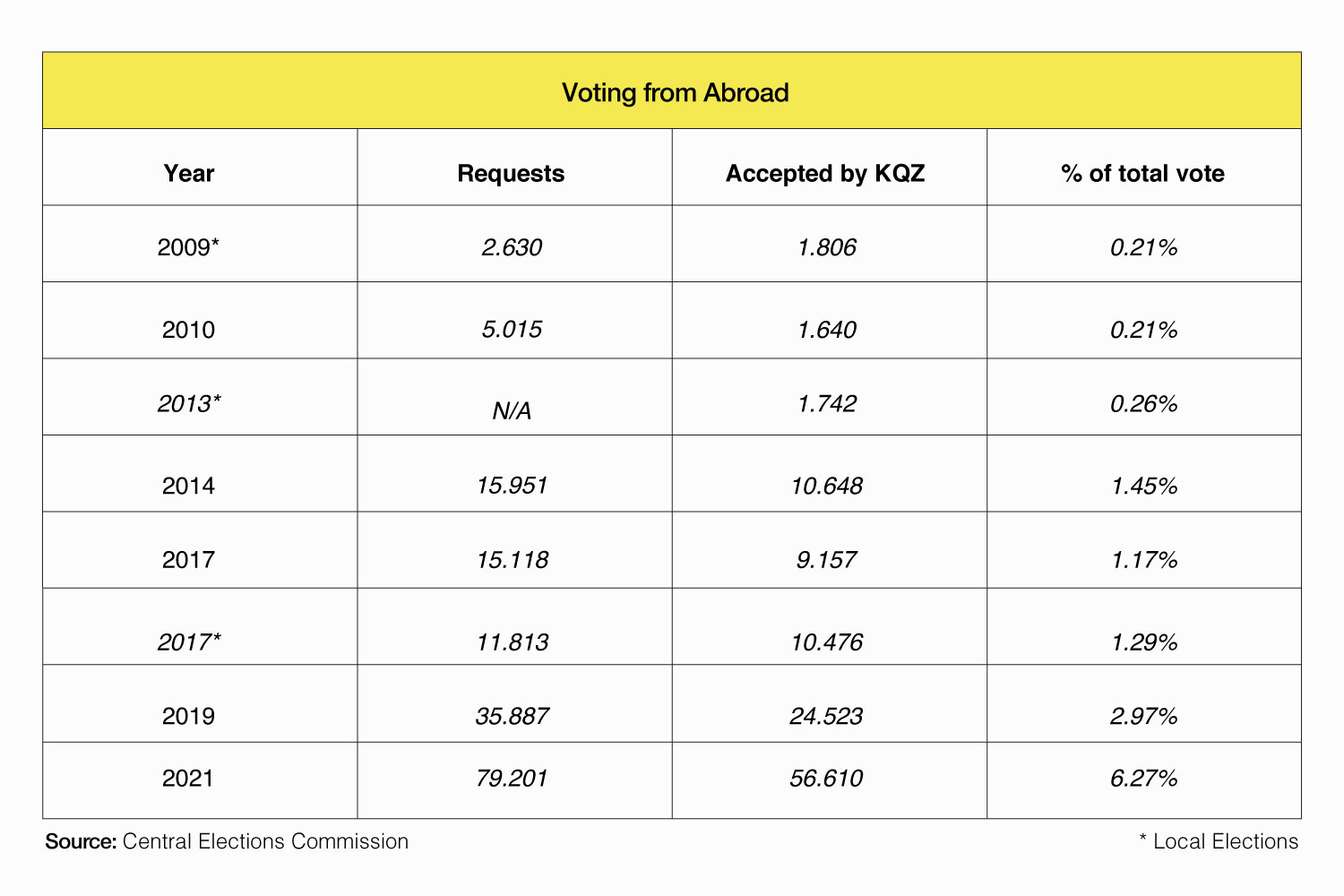

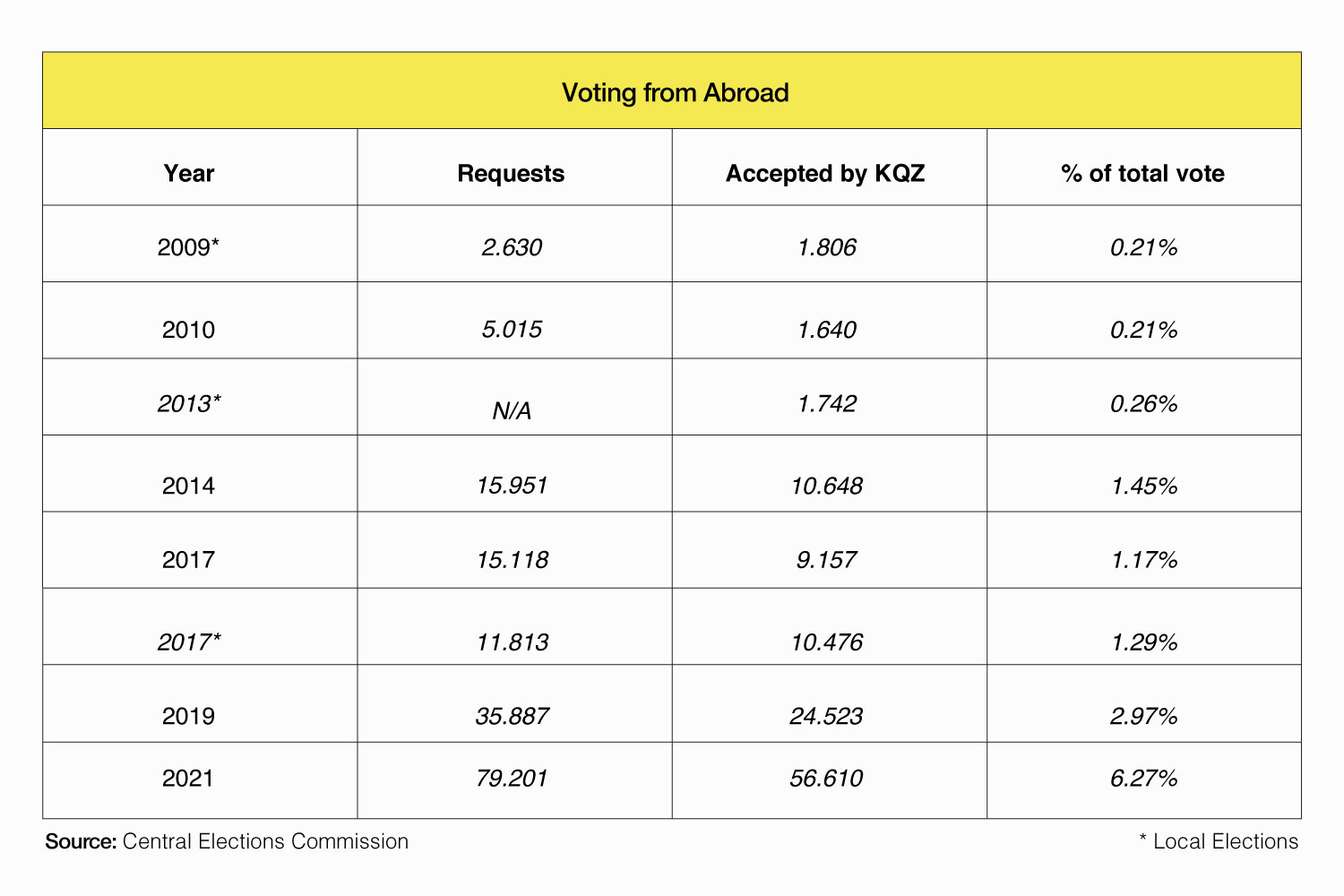

For the time being, the diaspora has been stuck with the current system, which requires onerous document reviews and a lengthy back-and-forth process with KQZ. As a result, despite its enormous size, historically the votes cast by the diaspora in electoral processes have only been around 1% of the total.

The interest in voting from abroad has steadily risen through the years and in 2021 there were some 56,000 votes, more than 6% of the total turnout, yet the process is still complicated, and often impossible to fulfill within the deadline. This leads to a substantial number of requests being rejected by KQZ. To bypass that risk, most diaspora members still prefer, even today, to travel back to cast their votes in their designated polling stations.

Political battleground

Facilitating voting and travel has very real electoral consequences. With so many potential voters living abroad, their participation has the potential to change the outcome of any election.

VV shares this view. The party has accused others of hindering diaspora participation to lower its chances, not only regarding verification and counting processes, but also related to travel rules. In the runup to the snap elections in February, VV accused the government of then Prime Minister Avdullah Hoti of using the pandemic as an excuse to discourage potential voters.

According to the party, the government was simultaneously easing restrictions domestically to boost its popularity and hardening entry requirements with mandatory isolation. This would complicate the kind of short weekend trips that often take place on electoral weekends, so VV considered it a targeted policy against them.

Since VV came to power in February, the role of the diaspora in national politics has been more controversial than ever.

The diaspora remains key for Kosovo’s economy, but public institutions lack a clear vision of how to steer its potential to the country’s benefit.

In early April, when the Assembly was at an impasse to elect a new president, and was on the verge of another snap election as a result, the VV-led government introduced a last second amendment to the electoral law. It would have allowed people to vote directly from embassies and consulates abroad, easing the process for hundreds of thousands of voters.

The amendment, which was introduced on April 2, was fast-tracked for approval before the deadline on April 5, the date by which the Assembly had to elect a new president or dissolve. The opposition, as well as many political commentators, was against the surprise proposal, seeing it as a power grab.

Ultimately the initiative was withdrawn and the Assembly finally elected Vjosa Osmani as the new President of Kosovo within the deadline. But the underlying issue of voting from abroad remains unsolved.

These events show that the diaspora has become an electoral battleground for political parties. Although VV reintroduced the amendment in June through an ordinary process, the Assembly is not in a hurry to complete it, and no development has taken place since.

With no further discussions on the topic, the debate has stalled amid other priorities. As a result, local elections in October occurred without any resolution to the challenges of voting from abroad.

The diaspora remains key for Kosovo’s economy, but public institutions lack a clear vision of how to steer its potential to the country’s benefit. The ruling party emphasizes strengthening links with the diaspora, but after the previous Strategy for the Diaspora expired in 2018, state institutions have been unable to come up with a replacement. A draft from that year remains gathering dust on a shelf.

In the meanwhile there have been patchwork initiatives such as the subsidy on border insurance. While this patchwork approach can help ameliorate narrow problems in the short term, they have their own costs and are susceptible to political gamesmanship. Without a long term strategy, these initiatives risk permanently politicizing the diaspora.

If engagement with the diaspora becomes simply a question of party politics, Kosovo risks wasting one of its biggest assets. Time is not on its side. While the first generation of emigrants tends to retain strong links with their country of origin, these are inevitably diluted as generations pass.K

Feature image: K2.0.

This publication was published with the financial support of the European Union as part of the project “Citizens Engage”, implemented by K2.0 in partnership with GAP Institute. Its contents are the sole responsibility of Kosovo 2.0 and GAP Institute and do not necessarily reflect the views of the European Union.