In Prague Street, at the very heart of Zagreb, a small group of women stand in bloody white dresses and T-shirts. The blood on their white clothes is intended to be a reminder of the many women in the past who were forced to perform abortions with a clothes hanger. Thirteen of them stand with their fists in the air in front of a crowd of people that are demonstrating their support for a ban on abortion by marching in the Walk for Life.

Insults can be heard from the crowd, directed toward the activists: “Četnik women,” “Serbian whores,” “Lezbos,” “Children murderers,” while the crowd sings the songs of Marko Perković Thompson, a singer known for his nationalist language.

After conservatives in Croatia began organizing Marches for Life against abortion, feminists in Zagreb started to organize counter-protests, defending what they believe is a basic freedom for every woman. Photo: Jadran Boban, courtesy of Ženska mreža Croatia.

However, the 13 women continue to stand resolutely in front of them. At one point, almost as salvation, the police stroll in. But the women know what is coming, so they sit down on the ground. Police officers come close, lifting the women one by one and taking them inside police raid vehicles. They don’t resist, but also don’t lower their fists.

The outcome of this May 25 protest, which they called “Freedom of Choice,” was a police report filed against the activists for violating public peace and order because their gathering hadn’t been reported in advance. However, the feminists who participated in the counter-protest believe that they were arrested because they stood opposite the supporters of the “Walk for Life” group.

In the same manner, activists had organized themselves throughout Croatia that day, going out on the streets and fighting for the right to make decisions about their bodies.

All of this is going on in Croatia, a country that is a member of the European Union, and that should be a role model for others in the region.

Tradition of Yugoslavia

Throughout history, the Balkans has been a place where patriarchy has stood as an obstacle to achieving numerous human rights and has seen policies imposed that manipulate women’s bodies.

A bright period happened in the time of Yugoslavia, when the system promoted the equality of women and respect for the rights of all. In this spirit, the right to abortion was legally regulated in 1952, but it still remained the only medical procedure within the health care system that was charged for.

A strong feminist movement in Yugoslavia helped to make it possible for the right to abortion to subsequently become a constitutional category in 1974; similar constitutional provisions existed in only three other countries in the world at this time.

In 1978, the Law on Health Measures for Achieving Rights to Free Decision-making on Childbirth came into power, further defining and clarifying rights. In most of the countries emerging from the breakup of Yugoslavia, it is effectively the legislation that is still in power. However, the voices of those who believe that this law must be changed, at the expense of women, are becoming increasingly vocal.

The ban on abortion means negating the rights of women to decision-making, and is considered to be a direct manifestation of hatred toward them.

The law defined that termination of pregnancy could be performed up to the end of the 10th week from the day of conception, and after that only with a commission’s approval. However, recently, in most of the post-Yugoslav states, doctors have obtained the right to refuse to perform abortion if it opposes their personal moral values. Simultaneously, voices have been raised by those who are against such legal solutions and who demand a full ban.

From a feminist and human rights angle, the ban on abortion means negating the rights of women to decision-making, and is considered to be a direct manifestation of hatred toward them. This misogyny has been depicted in the ecranized work of writer Margaret Atwood, “The Handmaid’s Tale,” which illustrates a dystopian outcome of years of hatred and constitutes a condensed depiction of all examples of banning the rights of women, with an accent on reproductive rights.

The TV series became part of the struggle for the right to have free decision-making throughout the world, hence the region as well. In Croatia, where the voices of those who oppose abortion are currently the loudest, feminists organized a performance last year, titled “Handmaids Standing Up for Istanbul Convention Ratification,” warning about the increasing influence of neoconservative voices, and the institutional violence that women are exposed to.

The Istanbul Convention, a document that came from the Council of Europe in 2011 and that is supported by feminists accross the world, explicitly condemns violence against women. Ultra consevrative groups in Croatia, who have large support in the government and church, were against ratification of the convention, and even organized the signing of a petition. Feminist groups responded by making an extra effort in their call for ratification and, following pressure from the EU, Croatia did ratify the Convention in 2018.

The struggle for women’s right to have control over their own bodies is also taking place in other countries in the region, where conservative voices can also be more frequently heard in the media, as well as in schools and health care institutions.

Leonida Molliqaj says that, despite the legal regulations as old as a few decades, pregnancy termination is still connected to morals and a woman's honor.

In Kosovo, investigative journalist for women’s rights Leonida Molliqaj says that, just as in the region’s other patriarchal societies, motherhood is considered to be the main virtue of women. At the same time, she says that women are being totally negated as sexual beings, as is the case with their rights to make decisions about their own reproductive rights.

The lack of space in public where women’s reproductive rights could be discussed leads to a large number of women not undertaking regular gynecological check-ups. Reasons for this include the existing stigma, as well as poverty. Unemployed women and those living in rural areas are particularly victims in this regard.

In legal terms, the main provisions of the law that was in power in Yugoslavia were effectively carried forward into Kosovo’s legislation such as those referring to women’s right to abortion until the end of the 10th week of pregnancy. After this period, abortion is allowed in cases of violence, incest or complications that may harm the health of women or influence the fetus if a mandatory approval has been received from a specially designed commission.

However, in practice things are different.

Molliqaj says that, despite the legal regulations having been in force for decades, pregnancy termination is still widely connected to the morals and honor of a woman.

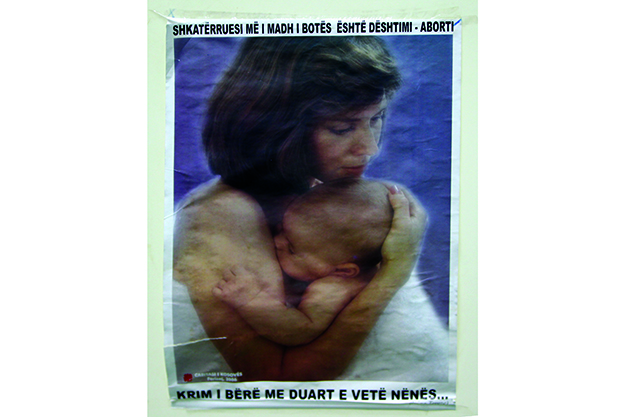

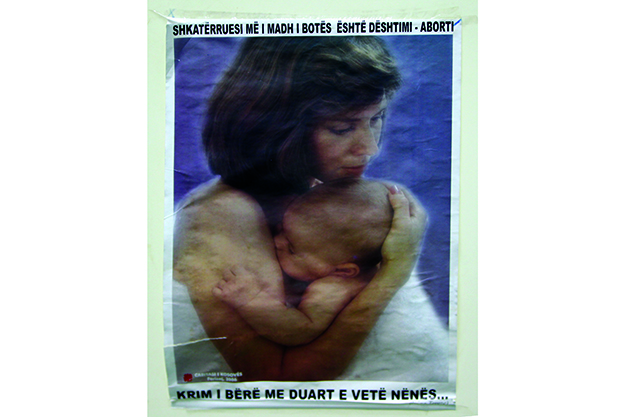

Those waiting for abortion consultations at clinics in Prishtina may be faced with moralising posters that decry abortion as the “most devastating thing in the world.” Photo courtesy of Preportr.

“However, the fact that abortion is considered an immoral intervention doesn’t have an influence on women not performing it but [instead means they are forced to] find ways to do so in great secrecy, which is directly endangering their lives,” warns Molliqaj, who also points to cases in which contraception pills are taken without prior consultation with doctors and abortions being performed in unlicenced clinics.

A negative attitude toward women and abortion is visible in the public arena as well. Women who go to Prishtina hospitals for an abortion are confronted with posters with captions saying “Abortion is the most devastating thing in the world” and “A crime committed by the hands of their own mother.”

Generally speaking, the story of sexual and reproductive health in Kosovo’s society is a topic sealed behind closed doors, as evidenced by a lack of mandatory sexual education.

Feminist struggles

Meanwhile, neighboring North Macedonia has learned that it is possible to drastically shrink women’s rights “overnight.” In 2013, a new law was introduced that practically disabled a safe and accessible procedure for pregnancy termination, particularly by forcing women to wait for commission approvals for a long period of time; in some cases this ultimately led to health complications.

The struggle of feminists has recently brought about a series of legal measures, which abolish compulsory counseling as well as the wait for an abortion approval. These changes enable a woman to carry out abortion until the end of the 12th week of pregnancy, as opposed to the end of the 10th week as was previously the case; a later abortion can still be perfomed in special circumstances where there may be an impact on the health of the woman or child, or if a pregnancy is the result of rape. Also, it is possible to perform a later abortion if the woman is faced with difficult living conditions.

In these special cases, a commission is to be assembled with doctors and social workers as its members. Women have the right to file a complaint against the commission’s decision. With the new provisions, it should be possible to carry out abortion in health centers as well.

While the restrictive law was in power, there was a reduction in the number of abortions carried out within state clinics, but the number of departures to perform medical procedures for this purpose in Kosovo and southern Serbia increased.

The official political discourse in Serbia — which is often close to the ideas of the Serbian Orthodox Church — promotes the “raising of birth rates.”

The restrictive law in North Macedonia received support from top ranking officials in Serbia. President Aleksandar Vučić pointed to the “Macedonian model” as a positive example, and said that he would want women in Serbia to hear the sound of a child’s heart beating.

Even though there is no abortion ban in Serbia, the official political discourse — which is often close to the ideas of the Serbian Orthodox Church, especially when it comes to abortion — promotes the “raising of birth rates.” Last year the government published an open call for slogans to encourage a rise in birth rates; in the space of a few weeks, the Ministry of Culture received a total of 1,002 suggestions.

Simultaneously, for more than two decades, the Serbian Orthodox Church has been sending public messages with the aim of creating an atmosphere that would lead to the banning of making information available on reproductive health. Under this influence, a package deal on sexual education was withdrawn in 2017, even though it had previously been approved by the government.

Jelena Višnjić, one of the founders of the feminist cultural center BeFem, says that church dignitaries do not hesitate to publicly vilify women who disagree with them by attempting to deny them the right to their own body and choice.

“This is a paradigm of a conservative, nationalist treatment, but also a value matrix used by the far right, common to different social circles,” Višnjić says.

She points to the fact that the issue of abortion has lately been returned to the parliaments of many countries, which she says is confirmation of the fact that we are living in societies that are deeply traditional and conservative.

“In the case of Serbia, this is a direct consequence of militarism, nationalism, wars, and a growing influence of the church,” she says, adding that the renewed abortion debate isn’t just affecting the Balkan region. “In Europe, this is a result of strengthening rightwing ideologies and the presence of conservative parties in parliaments.”

Problematic narratives

Višnjić highlights the conservative ideas regarding women’s rights among members of the Dveri political party, an ultraconservative organization in Serbia that has a section in their political program titled “Women will save Serbia.”

Some of the consequences of spreading these ideas are visible.

Within Serbia’s health care system, access to gynecologists often means fertile women being strongly encouraged to have children with doctors often providing uninvited counsel on how women can improve their health through pregnancy.

Even though, legally speaking, abortion in Serbia is still part of the health care system, where “non-medical reasons” are concerned the procedure has to be paid for. In state clinics, the price ranges from 150 to 200 euros, depending on the anesthesia used, while in private clinics, it ranges from 200 to 400 euros, depending on the method.

Problematic narratives focused on women in Serbia have been noted in observations made by the 2019 United Nations Committee on the Elimination of Discrimination Against Women (CEDAW).

“The issue of motherhood is a personal decision of every individual woman.”

Jelena Višnjić, BeFem

Višnjić explains that the Committee recommended the implementation of all necessary measures against the anti-gender discourse and its negative impact on the achievements of the state in the field of women’s rights.

“They observed the promotion of ultra-conservative ideas regarding the traditional family, with women primarily being seen as mothers, which further deteriorated with the national campaign for encouraging the increase of birth rates and adopting the Law on Financial Support for Families with Children,” says Višnjić, referring to the 2009 law that was amended in 2017 and again in 2018.

This law increases financial support for parental allowances, a main instrument of the pro-birth policy that is highly criticised by feminist organizations in the country.

She adds that campaigns for giving birth shouldn’t even exist, “because the issue of motherhood is a personal decision of every individual woman.”

Influence from nearby countries has also transferred to Bosnia and Herzegovina. However, as with many issues, Bosnia has many internal differences when it comes to abortion, and not only according to political positioning.

Women’s rights differ depending on the part of the country that they live in, whether it is Republika Srpska or the Federation of Bosnia and Herzegovina with its 10 autonomous cantons ruled by different political actors.

An association that is close to the Catholic church in Bosnia and Herzegovina has been prominent in its campaigning against abortion. Photo: Mlado sunce.

The differences are vast, from the issue of the right to pregnancy termination to medically assisted fertilization — women from Republika Srpska have the right to a larger number of free procedures of medically assisted fertilization in comparison to the Federation; there are also differences in terms of maternity pay, with maternity benefits differing from canton to canton as it is a locally devolved issue.

In the part of the country where the Croatian Democratic Community (HDZ) is in power, a right wing conservative party that often implements similar policies to those enacted by its sister party in Croatia, there have been attempts to impose an outright abortion ban.

In Široki Brijeg, Mostar, and Čitluk, many billboards with the slogan “Don’t give up on me, mother” were put up by activists of the Mlado Sunce association, which is closely associated with the Catholic church, while prayers were held in front of hospitals after the billboards’ placement.

Stigmatization of women

The legislation regulating abortion in Bosnia and Herzegovina has effectively remained unchanged since Yugoslavia, although conservative voices are becoming stronger. In Sarajevo, abortions can be performed only in rare private clinics and the public University Clinical Center. In each case, this service is charged for.

In private clinics, abortion is a big gray area and the rules differ. Some clinics don’t even pose the question of pregnancy maturity, while one needs to pay 250 euro for the procedure. In public institutions, the costs range from 80 to 130 euros.

At the same time, the discourse in which motherhood is the greatest sanctity and obligation has started to dominate the media, accompanied by a misogynistic tone for every other topic that directly touches upon women and their rights and bodies.

Selma Badžić from the Women’s Rights Center of Zenica (Centar za ženska prava Zenica) says that if a woman is a politically engaged public person who is young and educated then she is often scorned for being a bad mother; such women are also subjected to scrutiny on areas such as who is taking care of the children and why they don’t give birth to more than one child.

“This is where intimacy is deeply disrupted, as well as the right to choice of every woman, but also the physical possibility for her to get pregnant,” Badžić says.

She notes that media reports are often accompanied by an avalanche of comments, both on media portals and on content shared on social media, “which contributes to the spreading of conservative, stereotypical attitudes and hate speech against women in all aspects of their lives.”

“The context and very slippery slope have additionally been worsened by pro-life policies from neighboring countries.”

Selma Badžić, Women’s Rights Center of Zenica

A special attack on reproductive rights in Bosnia and Herzegovina is seen in the large amount of sensationalist media titles “on the fear of low natality,” while there are also claims that abortion is the cause of low natality.

They seem to be yet another attempt to place the blame for the state of affairs in the country on women; history shows that such efforts go hand in hand with the violation of women’s basic rights to freedom, choice, and control over their own bodies and lives.

“The context and very slippery slope have additionally been worsened by pro-life policies from neighboring countries,” warns Badžić, who adds that education in schools on reproductive and sexual health rights and sexuality remain a taboo.

She sees this type of attitude as something that is contrary to the global Sustainable Development Goals, a United Nations document that state-parties — including Bosnia and Herzegovina — have signed, obliging them to work on eliminating the inequality between sexes, among other things.

“Instead of that, children have religious class and teaching, with little space left for encouraging the development of a critical mindset or developing personal attitudes,” Badžić says.

“Religious events, dates, and gatherings are used to propagate claims that men must return to their role of being ‘head of the household’ and women should be ‘put in their place’ — the house, to clean, cook, give birth, and to take care of the children.”

Fighting back for women’s rights

However, scenes such as those on Zagreb’s Prague Street, which seem to be becoming more common, show that the most drastic campaign against women’s abortion rights in the region seem to be happening in the youngest EU state, Croatia.

As in other places, the legal framework governing abortion was simply transferred from Yugoslavia and remains unchanged. However, conservative currents under the influence of the church have long been focused on challenging the right of women to make independent decisions.

Paola Zore from the Platform Against Violation of Reproductive Rights (Obrani Pravo Na Izbor) — which consists of a group of activists working in the field of reproductive rights — claims that “attacks” on women and their bodies have intensified in the last five to six years. She believes that this is happening due to the appearance of new internationally linked and financed groups that are using different new strategies in an effort to get abortion banned.

“Even though more than 60% of citizens support legal abortion, this number was slightly higher in the ’90s.”

Paola Zore, Platform Against Violation of Reproductive Rights

Zore says that the Walk for Life, which has been organized for the fourth year in a row, as well as the prayers in front of hospitals, have helped to contribute toward enhanced stigmatization related to abortion.

“Even though, according to public opinion polls, more than 60% of citizens support legal abortion, this number was slightly higher in the ’90s,” she says, adding that abortion in Croatia is increasingly difficult to access, while a rising number of women who want to perform it are doing so in neigboring countries.

The public discourse in Croatia when it comes to abortion is also becoming more aggressive toward women. Media are increasingly focusing on the issue of abortion through saying that life begins at conception, talking about “abortion being murder,” and targetting women and the medical staff who perform abortions.

Besides the fact that this discourse completely excludes women and their right to make decisions regarding pregnancy termination, there are groups that provide support to pregnant women on the condition that they continue their pregnancy.

Zore explains how abortions in Croatia cost between 200 and 400 euros, while the prices are rising as the years pass, and there are differences between hospitals, “which creates the opportunity for them to start behaving as market subjects, determining the prices on their own.”

This relatively high price influences women’s decision-making on abortion, but perhaps a bigger concern is the fact that medical staff are increasingly utilizing their right to conscientious objection; according to some research, as many as 60% of doctors do so, while in five hospitals surveyed all of the employed doctors used their right to conscientious objection, and abortions are not performed there.

Croatian activists fear that the new law could introduce a number of obstacles to performing abortion.

Activists in this field also say that they know of doctors who privately perform abortions for additional money, which is illegal.

“The number of doctors who use their right to conscientious objection has grown over the last few years, and we expect it to keep growing,” Zore says. “Medical staff are using the right to conscientious objection not only in cases where abortion is requested, but also in the case of some procedures relating to medically assisted fertilization, and some diagnostic procedures during pregnancy.”

She says that other examples of medical facilities violating the right to abortion in Croatia include the unavailability of medicamentous abortion, the charging for diagnostic procedures that should be free, manipulation of information relating to abortion, and the refusal to conduct an abortion after the 10th week even in cases where the pregnancy is a consequence of rape or when there are serious malformations of the fetus that are incompatible with life.

In recent years, pro-life groups have challenged the constitutionality of the law regulating abortion, resulting in the Constitutional Court in 2017 issuing a deadline of two years for adopting a new one; this deadline has recently expired.

Croatian activists fear that the new law could introduce a number of obstacles to performing abortion. At the same time, they anticipate stronger campaigns to put pressure on women, medical staff and the public, and they expect further deterioriation of the conditions for enabling the right to abortion due to the implementation of the right to conscientious objection and the raising of abortion costs.

Pro-choice activists have stepped up their actions in the face of increasing anti-abortion pressure in Croatia. Photo: Jadran Boban, courtesy of Ženska mreža Croatia.

But while pro-life groups have sent their proprosal to the Croatian parliament as part of lobbying for stricter abortion legislation, feminist group are not just sitting by and passively waiting for what may come.

In addition to sending their own proposals for the new abortion law to the parliament, feminist groups such as Autonomna ženska kuća (Autonomous Women’s House) — who organized the May 25 “Freedom of Choice” counter-protest — have also initiated a number of campaigns demanding freedom of choice for all women.

Another campaign group is Crveni otpor (Red Resistance), which has called on all those who support them to wear something red on the days of the U.S.-inspired Walks for Life in their own “Walk for Freedom.”

The first Walk for Freedom counter-protest in Croatia was organized back in 2018 in Rijeka, but there have since been plenty more.

Marinela Matejčić, a member of the Građanke i građani Rijeke (Rijeka Citizens) initiative, says that organizers of the Walk for Freedom in Croatia want to assemble allies and point out the relationship between attacks on reproductive rights and other social processes, such as the strengthening of fascism and historical revisionism, and attacks on public assets.

“On the other hand, Rijeka Citizens, as an initiative encompassing many individuals and members from the civil sector, recognizes the continued attacks on women’s rights as an important aspect of the struggle, but also within the wider context of violating human rights in this country,” Matejčić says.

Ultimately, while the region’s countries tend to have a lack of unity over political issues, when it comes to the lives and rights of women, they have plenty in common.K

Feature image: Jadran Boban, courtesy of Ženska mreža Croatia.