Among cultural and artistic circles in Kosovo and beyond, Sezgin Boynik is known for his propensity to unravel under explored artistic endeavors. His treasure hunting starts by being drawn into coincidences that fall into causality given the complexity of human relations, artistic movements in history and the present that go beyond nations, imperial projects, beyond stigma.

Thanks to his deep interest in the Russian avant-garde or Russian Futurism, Boynik made the rare discovery of the play “Yanko, King of Albania” published by Ilya Zdanevich in 1916. A Georgian writer and artist, who rebelled against Pan-Slavic Russian imperialist aspirations in Albania, disrupted the racist view on Albanians during that time, paying outspoken tribute to the Albanian struggle for independence, albeit in a language not easily understandable by others. It is written in Zaum, an artificial language. Avant-garde writers sought to establish a language that opposed the language of the bourgeoisie, a language that goes beyond conformist ways of understanding meaning only in “civilized articulated culture.”

Reviving the legacy of anti-fascist colonialism interwoven in abstract art forms, Boynik initiated the first translation of “Yanko, Albanian King” for a wider audience to understand that there was a nonconformist union in the first World War. The first World War, being a time where even immobile peasants knew about cities like Durres, as the place in the sun, and was seen as needing to be conquered, controlled and the Albanian “barbarians” needed to be “civilized.”

The project is part of Pyke and Shuplak-Shuplak Press, a research platform based in Prizren, that Boykin founded with Tevfik Rada and Vernon Shukriu. The book will be published by Rab-Rab Press, hopefully in spring 2021.

Following it’s presentation in January at Kino Armata that was organized, funded and supported by by CHwB Kosova, Kosovo 2.0 sat down to talk to Sezgin Boynik about the Russian avant-garde, the mysterious life of Ilya Zdanevich, the representation of Albanians and the presumptuous but violent threat of imperialism at the doorstep of Albanians.

K2.0:Who was Ilya Zdanevich?

Sezgin Boynik: Ilya Zdanevich was born in 1894 in Tbilisi, the capital of Georgia, where he lived parts of his life moving between Tbilisi, Saint Petersburg and Paris. He was a writer, typographer and artist. For most of his life, he earned his living doing design work for Coco Chanel and designing special artbooks for well-known artists such as Picasso and Max Ernst. But most importantly, he was part of what came to be known as the Russian Dadaist scene in Paris, the Russian avant-garde and specifically Russian Futurism.

The avant-garde epoch began in the early 20th century, with artists and writers transgressing aesthetic and social norms, disrupting established canons of taste, scandalizing by going against the norm, also speaking from the margins of society. Can you elaborate briefly on the Russian avant-garde and Russian futurists?

In the history of the avant-garde it is important to make the difference from Western avant-garde. Russian avant-garde went to the extreme of the abstraction of things, against objectivism, against the norms that differed from Western avant-garde. It was simultaneously and continuously theorized.

As Eric Hobsbawn said, the first world war was a lesson of geography. It sounds strange but that was the spirit at the time.

Were they also more explicit in their political connotation?

Not in the beginning. There was no explicit political connotation, no. If there was something in common to the Futurist it is that they hated the bourgeoisie. They despised the norms of bourgeoisie, their utilitarianism, the simplistic language of the ruling society, a commons of society that was mostly mediocre bourgeois middle to upper class. There were futurists who lost their way, who turned right-wing and fascists, supporting war and militarism, like the Italian Futurist Marinetti who then supported Mussolini. But Russian Futurism was de facto anti-war, anti-military and saw war as a regression that only makes elites rich.

So, Ilya Zdanevich was part of a network of Russian futurists, who with their writings and artistic endeavors stood against imperialism and oppression. Getting back to his persona, how did working with established artists and design groups such as Coco Chanel influence his efforts?

That is the interesting part about Ilya Zdanevich; he was connected and well known to more established artists but was always invested in exploring the margins of society, he stayed at the margins for most of his life. He did all kinds of things, researching on mysterious figures of the 18th century poets, astronomists and alchemists. All kinds of strange, underexplored topics. He was also a Byzanthologist, wrote philosophical essays, invented new forms of poetry such as “visual poems.” So, among his scene and with researchers of today, Zdanevich is known as a figure who influenced his surroundings very much. In this sense, also “Yanko, Albanian King” is a well known play.

Is it maybe through this context that he became interested in the Albanian struggle for independence, an underexplored topic cast aside during the period of the imperial powers?

Yes, pretty much so. I must say, Albania was very important to Russia in the first World War because Russia was fighting against Germany, within the Entente alliance, which France and Serbia were part of. And Russia with Serbia had this Pan-Slavic idea of reaching Albania, reaching Durres, a place in the sun. Through their imperialist projects, simple people in Russia, even peasants who never traveled outside their village, knew about Albania due to the imperialist fantasies. As Eric Hobsbawn said, the first world war was a lesson of geography. It sounds strange but that was the spirit at the time.

Yet the play “Yanko, Albanian King” was from the margins?

It was a play opposing the racism against Albanians that prevailed at that time. The Tsarist regime of Russia propagated that Albania was a barbaric land that needed to be controlled, subsumed under the Russians and Serbs and civilized, run, administered. So, “Yanko, Albanian King” is not a play analyzing Albania, it is a critique of the Russian view of Albania.

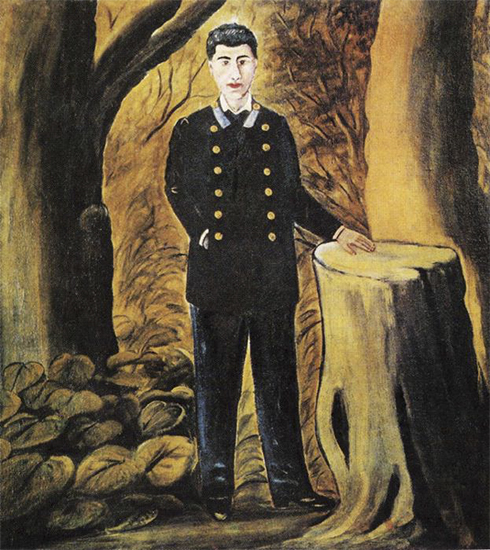

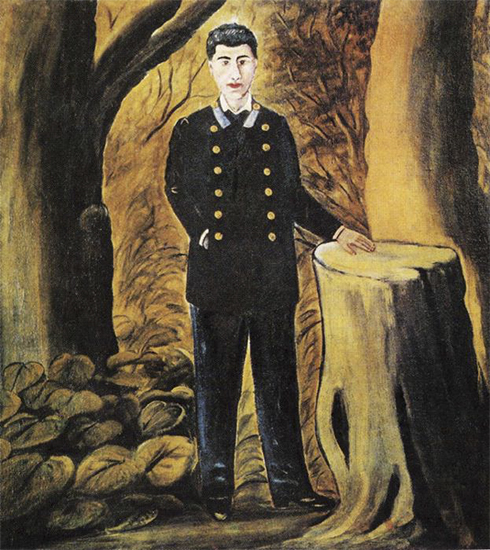

The discovery of the play “Yanko, Albanian King” was presented at Kino Armata in January 2020 by Sezgin Boykin. Images from “Yanko” are stills put together into a video by CHwB Kosova.

By that time, the imperialist fantasies of Russia targeted other groups as well, how did Zdanevich, a Georgian writer, become interested in Albanians specifically?

It all started with his travel to Saint Petersburg at the end of 1916, before the October Revolution. He met with a very Dadaist and Futurist group publishing an anarchist avant-garde magazine called “Bloodless Murder.” At the peak of Russian Tsarist oppressive regime and the peak of WWI, they published several issues — a brave move at that time.

Within this subculture, Zdanevich connected with Olga Leshkova, who showed him an issue of a magazine, entirely dedicated to Albania. Not analyzing Albania, but criticizing the racism toward Albanians.

Was there a particular reason for them to write this issue at that time?

What happened was that a sympathizer of the leftist Russian Futurism,Yanko Lavrin, who was born in Slovenia, changed sides radically in 1915. He turned conservative and then nationalist. Working as a writer at that time for pro-monarchistic magazines such as “New Times,” Lavrin was commissioned to do a reportage on Serbia, Yugoslavia and Albania. And the reportage turned out terribly racist. This was followed by a book “Albania Land of Eternal War,” a terrible colonialist view on Albania portraying the people as bestial, beyond any notion of culture, talking about them in the most terrible terms. After this publication, Russian Futurists, including “Bloodless murder” made him into an enemy. They dedicated a whole special issue of their magazine to critiquing Yanko Lavrin’s views.

Is this where the name of the play comes from?

Yes, so when Zdanevich read the issue and talked to the publishers, he was touched by this brutality and was outraged about it. So he decided to write a play, a mockery of Yanko Lavrin, fictionalized into “Yanko, Albanian King.”

Now, I think it is the right moment to jump deeper into the narrative of the play. What does Yanko want, is he the hero, anti-hero, what is his conflict in the play?

There is Yanko, who wants to become the King of Albania but he is frightened. The play begins with a dancing quarrel between a group of Albanian bandits and Yanko. The bandits ask: “Where do we get the king?” At this moment Yanko is playing with a flea.The bandits seize Yanko and demand that he becomes their king. He has a great monologue as the king. But the bandits and Albanian people call Yanko a donkey. Prenk Bib Doda (a dubious character) lubricates the throne with glue. Yanko tries to unglue himself with the help of a German doctor. But Yanko cannot peel himself off and is stuck on the throne. In the end, the bandits kill Yanko.

There was no confusion about the fact that Zdanevich’s play was going against the system in power.

That indeed sounds like an absurdist play. Yet, the Albanian takes up the part of being violent self-organized barbarians from first appearance. How can you then determine that it was subversive and supported the Albanian’s struggle against Pan-Slavic imperialism?

The first thing that must be said is that the whole play is very Dadaistic, experimental so to say. You don’t get much of his social analysis and historical context. But you get one thing very clear, that he was absolutely against imperialist, racist, nationalist, Pan-Slavic, Pan-Russian aspirations.

How so?

The play is a mockery of the real Yanko, who in the play is played out through the figure of a want-to-be but yet too weak king, who suffers from his presumptuous superiority complex. And then you have the bandits opposing him, overthrowing the king. The play has a host, based on Zdanevich who introduces the context of the play in a kind of Brechtian intervention, embedding it into the context.

The play uses absurdist techniques to make a point about anti-Albanian racism and Imperialist fantasies. Images from “Yanko ” are stills put together into a video by CHwB Kosova.

So, we can find out more about the play when looking beyond the narrative, toward stylistic devices and form?

Yes, the play is a mixture of cabaret, opera, absurdism. There was some kind of madness inflicted in the tones of the play, a critique of war yet not fully there. You have to know when Zdanevich wanted to publish the play in 1917, he was censored by Russian Tsarism due to his obscene verses and mockery of officials and kingdomship. There was no confusion about the fact that Zdanevich’s play was going against the system in power.

As I read the play was written in Zaum, an alternative language invented by Russian Futurists, using phonetics and abstracted words from languages to aesthetically form an anti-language?

Zaum was invented by Russian Futurists, not necessarily as an anti-language, but a language in itself. A language going beyond our prefabricated ways of finding meaning. Their theory of Zaum was based on this idea, to find out what is the real constituent of language as material. Because when you write poems, you use the same language as Russian or Albanian, common words that already have a life. In poetics, language is different, language is transformed. Later then, the Russian Futurist theater was using Zaum in their plays, with Zdanevich being a pioneer. Yanko was his first Zaum-play, later called “Dra”- Plays.

The play will be published Spring 2021. Images from “Yanko” are stills from a video by CHwB Kosova.

What was Zaum and how was it used in “Yanko, Albanian King” and what did it give to the play that supports understanding it’s message today?

Zaum discovers the elementary, the core, that connotes their social and political analysis. For instance, they opposed the conventional language as bourgeois language, their diluted understanding of what art is and should do. To abstract and be free from norms was their way to approach things. In language they invented a language that went beyond national languages, which was then called Zaum.

Using phonetics as abstracted from Russian and other languages, Zaum is an encrypted language, invented words, some pronounceable others not, some longer some just noises. So, you can trace a lot by immersing into the usage of language, and the interplay of semantics and sounds is very crucial for this play. It is written and performed in Zaum with some understandable words in common language, mostly Russian.

What does the Zaum language look like? Here are the opening lines of “Yanko, King of Albania”:

deer sitizens heer iz ðe akt janko kiŋ of albejnja baj fejmas

albejnjen poet brbr birzhofka hiro dedikejted to ol

ga ljashkova heer ðej du not speek albejnjen and bladle

ss merdr produses akt alas wiðaut translejshn

bekoz albejnjen lengweg livs alongsaid inglish stems from yt ju

maj obzerv werds whitsh rizembl inglish satsh az ass klatz

gamshu and sou forth bekoz words in albejnjen hav

non inglish meening satsh az ass meening (ai omit meening

thru nou folt of majn) and sou on whitsh iz whai dount worri

remembr satsh iz ðe albejnjen lengweg

—This is an English Zaum translation and then the play continues with clear humoristic devices and infantilism.

Can you give an example in relation with the representation of Albanians in the play?

Yes, sure. For instance, in the play the wording “free turpentine” is mentioned repeatedly, which is abstracted Russian for “Free Shqiptar” referring to Albanians, a strong element, which cannot be incorporated in an ordinary, conventional, civilizational language, but it is like a beyond-sense.

Here the perception of Albanians is deconstructed through a language that was perceived as more advanced than the normative language of Western civilization, in this language Albanians are spoken about. It is beyond cultural language. It is avant-garde, it is a Zaum and it is de facto accepting the demand of a free independent Albania.

But isn’t it non-emancipatory to not use the language of an oppressed group?

You have to understand that for Russian Futurists Zaum was going beyond the structuring of languages into culture and nationalisms, it was beyond notions of civilization, better than civilized normative language would be, so giving Albanians this speech in the play was emancipatory. At the same time, the character of the German doctor speaks a parody of German, which makes him look stupid. But the bandits are strong, as a revolting proletariat. Albanians, speak and sing, in most part, pronounceable and unpronounceable words abstracted from some alphabet, delivered with different intentions. You have to understand that Zaum is like a rebus, it can have many layers, it has many story lines, and is very complex.

So, Zaum communicates tensions through rhythm and sounds?

Yes. Russian Futurists discovered that it is mostly the rhythm which gives more dimension to words. Logically they were asking themselves if the main constituent to language is sound, do we actually need legible words? Can we make a speech, a poem, only using sound and rhythm? And there comes Zaum, the beyond-sense. Because their idea was when you read a text with words, the subconsciousness sets in and somehow you detect the rhythms. That is the history of Zaum, it started around 1913 and 1914 and was influenced by the general avant-gardist attempt to abstraction and nonobjective representation.

Generally, “Yanko” is a legendary piece for all who were part of avant-gardism.

Where and when did you discover the play initially?

I came across his work, when I was invited to an artist residency in Tbilisi, Georgia in 2014. By that time I was interested in what happened to the Russian Futurists who left the Soviet Union after the October revolution and went to Georgia. From 1918 to 1921 until Georgia was occupied by Bolsheviks from Russia, it was run as a country, in a socialist experiment. It was socialist leftist but unlike the Bolsheviks the idea of a democratic Socialist Republic of Georgia was coming out.

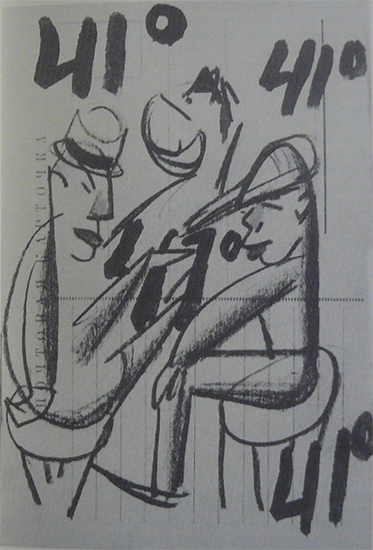

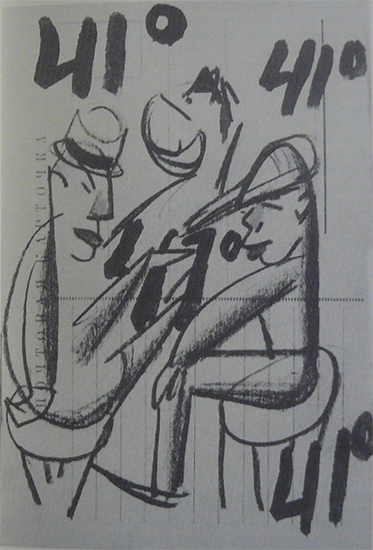

And it was exactly in this time, when Ilya Zdanevich was living there among other Russian avant-gardist poets, such as Alexei Kruchonykh, founded the publishing house 41 degrees.

Yanko, was part of the underground legacy and contextualized it. What was the reception of the play?

It was very good. Although Zdanevich did four more plays in Zaum language, which were far more complicated in the design, and far more advanced in the use of the language, he seemed to have a special dedication for his first play “Yanko.” Also his extended group of established avant-garde artists considered “Yanko” as a “classical Zaum.” Alexei Kruchonykh, always pointed at “Yanko” as the best example of Zaum enabling us to understand the social and political aspect of the avant-garde language.

Where did the play premier? Was there more than one staging?

It premiered in Saint Petersburg in 1916. Reconstructing the first performance, it seemed to have been celebrated with festive dancing afterward. It was quite brave to perform this in that time at the peak of WWI. Later in 1922, Zdanevich was invited by Viktor Shklovsky to Berlin. Berlin was the epicenter for Russian avant-garde and Shklovsky was a very important Russian Formalist and writer.

Although Zdanevich became admired for his more advanced “Zaum” plays, he performed “Yanko, Albanian King” in front of established personalities. A year later in a lecture in Paris, Zdanevich explained that Berlin had become “kitsch” popularizing the avant-garde, with “Yanko” he felt he performed an honest marginal original work. Generally, “Yanko” is a legendary piece for all who were part of avant-gardism.

Ultimately, “Yanko” is a singular piece from the Russian Futurism movement. Photo by Brilant Pireva.

Do you hope to find an audience in Kosovo and Albania too? Why do you think it is important nowadays to go back to avant-garde culture and Russian Futurism?

Well, my opinion about experimental art forms is very clear. Let’s say how we present history seems sometimes linear and parallel but avant-gardist, experimental approaches and artistic devices have the potential to multiply history. History is very dialectical, there is condensation, emptiness, you cannot tell history as a shortcut.

So, I think avant-garde forms can represent this better than traditional historical events. There are many more details than one aspect. See, just looking into Kosovo and Albania in 1916 we see the traces of Russia, Yugoslavia, Serbia, France, politics and economies all speaking about dynamics of power. So tell me which of them do you then explore first, which do you exclude, what do you prioritize?

Well the more you know, the less you can exclude.

Exactly. But you can have an idea on what is important, or focus on one device and circle around that. And that’s what experimental art does. It is an invitation to explore these dilemmas, to delve into the elements. That is why it is so important. It sounds like a cliché but the best to describe this is Walter Benjamin’s study of the 19th century, where he initiates a fragmentary research project pushing us to wake up from the “dream of the 19th century.” Zdanevich is part of that, he wants to speak from the margins through using distorted and unconventional elements and forms. I hope that all people will be interested in this, not only in Albania and Kosovo of course. It can bring a lot to many regardless of where they are from.

Do you think, if people would engage more with the avant-garde it helps to comprehend history in a way that is less influenced by Western ideology?

Yes, Western ideology and less of the nationalist ideology when it is very simplified. We have to learn to explain the history of the 20th century that debunks conventions.K

Feature image: Majlinda Hoxha / K2.0.