The PM’s draft agreement with Serbia reflects good intentions but may have dangerous consequences

An alternative to partition and territorial changes but still dangerous for Kosovo’s sovereignty.

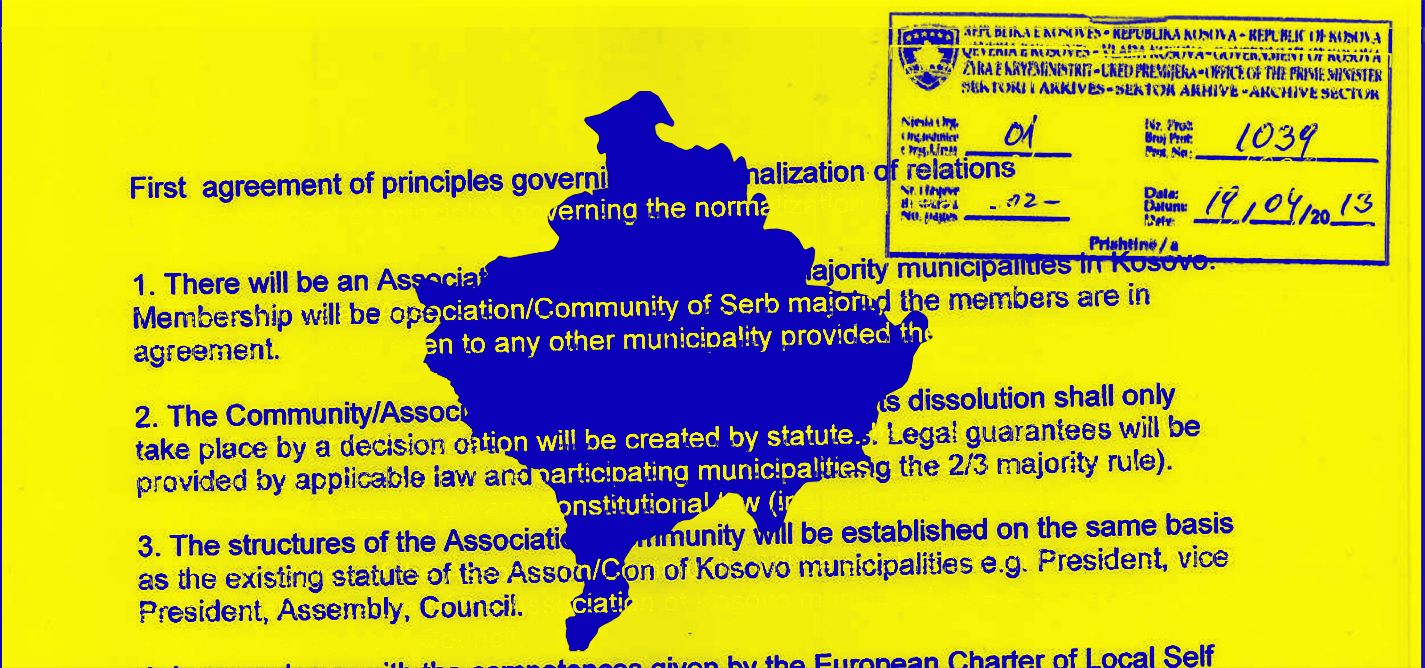

While the draft points in the right direction and has positive elements, it has certain shortcomings that may be politically and legally dangerous for Kosovo.

Robert Muharremi

Robert Muharremi is assistant professor of public policy and governance at the Rochester Institute of Technology — Kosovo Campus. Since 2000 he has served in various international organizations and government institutions in Kosovo as legal and policy adviser.

DISCLAIMERThe views of the writer do not necessarily reflect the views of Kosovo 2.0.

This story was originally written in English.