Gill Phillips knows a thing or two about the legal side of working in the media. Since the 1980s she has been an in-house legal adviser to world-leading organizations, from the BBC to The Times, and since 2009 she has been the director of editorial legal services at The Guardian.

During that time she has seen the media profession change enormously, moving from the daily routine of print editions, to wide scale digitalization, rolling news feeds and the birth of citizen journalists via social media. But the main pillars of her role have remained in tact: working with journalists and editors pre-publication to try and head off any potential legal difficulties, and dealing with any legal cases post-publication.

In recent years, she has been at the center — although behind the scenes — of some of the world’s biggest stories. She provided legal advice to the editors and journalists working with Edward Snowden as he leaked classified National Security Agency material detailing intrusive government surveillance, as well as working on cases including Julian Assange and Wikileaks, the Pentagon Papers and the Paradise Papers.

In the wake of these cases, she points out that the role of a journalist is becoming increasingly dynamic, and that it also has an ever-wider number of potential dangers.

State surveillance of journalists has significantly added to the pressure of the job, while a number of high profile murders in recent years have added to the impression that journalists are increasingly endangered in their profession; Europe alone has recently witnessed the brutal killings of journalists in Denmark, Malta, Slovakia and Bulgaria, as well as the disappearance of a Saudi journalist and dissident in the Saudi Embassy in Istanbul.

And states, she says, seem to be becoming increasingly paranoid. Governments of countries around the world, including countries with advanced democracies, do not hesitate to put pressure on investigative journalists, especially when investigations are looking into cases of corruption at the highest level of government, or issues that are seen as too sensitive.

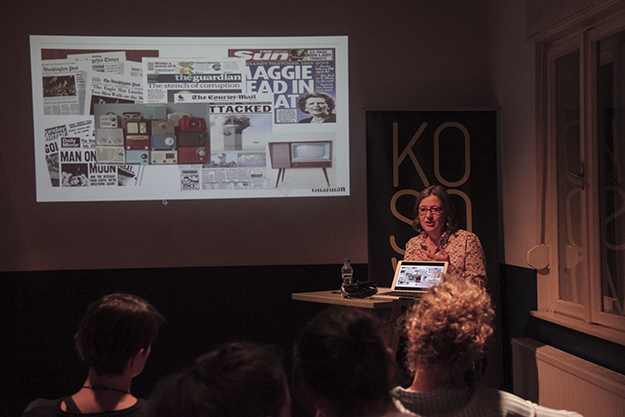

Photo: Atdhe Mulla / K2.0.

In the latest edition of K2.0’s Volume Up program, Phillips came to Prishtina to deliver a public talk on the lessons learned from years of ensuring the legal safety of world-leading journalism, and to deliver a training session for Kosovar journalists and legal experts.

K2.0 sat down with Phillips to talk about the role of a media lawyer, her experience of working on the very biggest whistleblower cases and the changing dynamics of holding states to account.

K2.0: This week we have heard about the murder of a journalist in Bulgaria. She’s the fourth investigative journalist to have been killed in the European Union this year, and while the motivation behind this murder remains unclear it adds to a sense that it is becoming more dangerous to do this job. So how does that affect the media in general and what is the message that is sent given that these crimes have so far gone unpunished?

Gill Philips: I think that there are all sorts of messages. One, it makes journalists, and indeed anyone who falls within that quite wide definition, whether they’re citizen journalists, it’s got to make them worry about what they write and the consequences of what they write.

I think that there’s a failure of governments to even look properly as if they’re investigating these things, and there’s sometimes a sort of flurry of activity and then nothing happens and they rarely seem to find the perpetrators. If they do, there is a tendency, I think, to say, ‘Well, hang on a minute, that’s a stooge, that’s not really the person behind this, it’s someone whose been paid or set up.’

Another thing that worries me when I read about these stories is that quite a lot of them sound as if they’re state sponsored acts, as though states are behind them in some way, whether directly or indirectly; the murder of the journalist in Malta last year, what’s going on with the Saudi Arabian journalist who has disappeared in the Saudi Embassy in Turkey… All of that sounds like states doing things and that’s very worrying.

"I think what Snowden showed was the extent to which states survey journalists and private citizens and the extent to which that impacts on journalists."

I mean, it’s always been the case. Journalists’ primary duty is to hold power to account and that often now reflects on the states, so to that extent these things are as they always have been, but the level of violence and intimidation used is much more worrying.

Is this the post Edward Snowden world that we’re living in? Can you connect it in any way even with what’s happening with Julian Assange?

That’s a big question, really. On one level, no, because these things have always been there and organizations with a mission to protect journalists like Reporters Without Borders have been counting journalists’ deaths and threats long before Snowden, so those problems have existed before that.

I think what Snowden showed was the extent to which states survey journalists and private citizens and the extent to which that impacts on journalists. And the fact that that’s sort of what was brought out — these mechanisms that states are using.

Even in the UK we had the Investigatory Powers Act, which really all it’s doing is making more open what they were doing before, but they were always doing it: gathering up data, snooping, checking, using side alleys to get to journalists.

I think that what he did was that he brought it much more out into the open, but I think that Snowden was much wider than just journalists — it was about private citizens. And, being in the Balkans this may resonate more. One of the things I read about why Snowden has more impact in some parts of Europe than it did in the UK was because we have never been occupied by a country for hundreds of years, whereas most of Europe has very recent experiences of having governments imposed on it that they didn’t want; so people’s levels of suspicion and appreciation of the dangers of government surveillance — knowing what you did and what you’re looking at — is much more real.

And that’s why I said some of it resonates more here, more so than in the UK, curiously, where people sort of seem to go: “I don’t really care, I’ve done nothing wrong.” And we all know the dangers of saying that until someone says: “You have done something wrong.”

If we can continue a little with the Balkans now, since you mentioned it. The reality in the Balkans is that investigative journalism, if it exists at all, is generally in a very bad shape. We have presidents that are autocrats, we have Aleksandar Vučić in Serbia who was head of propaganda during the Milošević era. We have states that are semi-protectorates and that are not very stable, and we don’t have many lawyers who are dealing with the media. How much is this really something that the world and Europe should look into more carefully?

For the last five or six years I have had the chance to come over to this area quite a lot; I’ve been to Serbia and talked to Serbian journalists, I’ve been to Bosnia, I was also in Montenegro in the summer, and I do have a sense, but I don’t have a sense of the difficulties that are part of the new democracies — the youth coming through into the old established regimes, which are resistant. Autocratic regimes never like free speech because it’s challenging them.

I think that we have to put that into a wider context of what’s going on now with journalists generally in the world, the commercial pressure with the fact that print everywhere is suffering, so it’s hard commercially, and that also if you add the fact that the level of violence and intimidation, not just here but in other parts of Europe where you might not expect it, like France — America has also seen journalists been killed — so it is a very hard place to play your part.

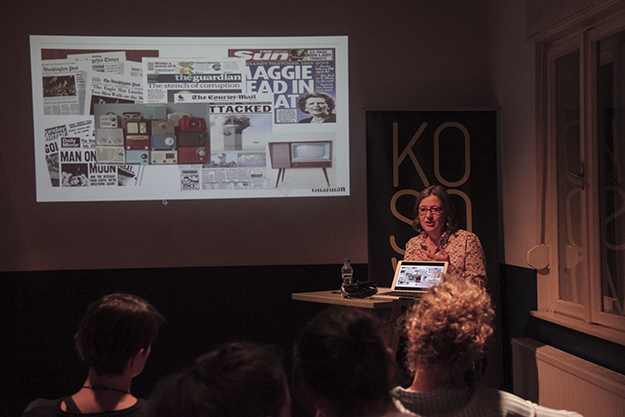

Photo: Atdhe Mulla / K2.0

When I was in Belgrade there was a whole story going on about redeveloping the Belgrade Waterfront, and people had come in there one night — this is what I have heard — and just sort of completely run riot through it, and people had been saying, ‘What’s going on? What’s happening?’ And none of it has been reported, other than a very small number of outlets who were then threatened.

These sort of things seem to happen more in the Balkans than in Western Europe, where they may have happened years ago, but you are experiencing these things in a much tougher commercial environment, and timewise it’s all much more compressed, so it’s happening in two years rather than over 30 years. That creates a very difficult landscape, particularly here.

But I have been impressed by the youth and energy of those investigative online journalists; again on the Serbian side, it was clear that people have been targeted, probably by the government in various ways. The privacy of investigative journalists was being attacked.

Since we mentioned Snowden, what can we learn from the challenges and the risks that you and your team went through during these cases? And what can we learn from them here in the Balkans?

I think the one big message that has come out of Snowden and these other big data stories is collaboration, which is different from the past where journalists would not share the exclusivity. All these stories — Snowden, the Paradise Papers, the Panama Papers and other tax leaks stories — have been collaborations, where journalists around the world have worked together on stories and they are sharing the exclusive.

They have an embargo and they agree on certain basic things; they don’t interfere with each other’s content but that allows them to properly explore these enormous amounts of data, which are huge, and to share their expertise, to spot things that others may not spot because they know about something, and to do it in a reasonably timely way. And I think that gives you the ability to interrogate the data and it gives you a considerable amount of safety in numbers — if everybody is doing this, the fact you are not just one lone voice. And I think that’s something for the Balkans — being part of these bigger projects.

Because, at the end of the day you are still an individual, but when you are with a group of people you sort of hope that governments may say, ‘There’s no point in us trying to knock them out’ because it’s going to come out here, here, here and here. I know that governments may still feel that they can do that on a local level, but internationally that has become much harder.

For The Guardian when we started doing these stories, the Wikilogs was probably the first one that I did personally, and back in those days one of the big threats in the UK was pre-publication injunctions, which are still a threat, but the fact is that when you’re working with a group of people the government recognized there was really very little point in saying ‘We’ll stop The Guardian publishing this story,’ because the reality was that American papers and other European papers were going to publish these things.

"There’s more willingness now from the government to have discussions, rather than threats."

So, [the government] weren’t going to stop the story coming out so actually what that meant was that they probably needed to have more of a dialogue with the journalistic organization. And that has to be a good thing. If there’s some particular bit of information that the government is worried about coming out for safety reasons, they can tell you and you can decide not to publish it. But you can also put the difficult questions to them.

In America, pre-publication threats in America are pretty non-existent, and so what that means is they have a much stronger dialogue — I’m not so sure if it’s the same thing now with Trump, because he’s not particularly a man for dialogue.

Generally, what they say in the UK is, ‘Go away, we don’t need to talk to you, we’ll injunct you if you go anywhere near this.’ Whereas when you do these big collaborative stories, that has no effect. And I think that has also spread more generally, so there’s more willingness now from the government to have discussions, rather than threats.

But also one of the other big things that came out of Snowden is that you don’t just need journalists but you need people that understand data and who can work out how to search it.

So, just the technical side of data searching and analysis and words and all that — clearly that has been a big development that has come out. Modern journalists need to be able to go out on the streets and be able to do the old foot-leather stuff, but they also need to have an understanding of those sorts of techniques or know people who know how to do them.

What is the role of media lawyers, because we don’t have many in the Balkans?

It’s a luxury, I know. When I started in the mid-1980s, most national newspapers and the BBC had small teams of lawyers but they didn’t always employ in-house lawyers, but gradually they realized that there was a benefit to it — financial, speed, knowledge, knowing the journalists, being available — so they started employing. But most regional papers in the UK don’t have any in-house lawyers, they have an outside lawyer they can go to.

My job now, as it’s always been, is mainly twofold. One is doing pre-publication work, because the UK has quite restrictive libel laws and we have to be quite careful about what we publish; in my small team we look at what we are publishing and make suggestions on how to change articles — little words.

For example, if you use the word ‘lie,’ that suggests that someone has knowingly told an untruth and that they know that it’s wrong, whereas not everybody lies. Sometimes they say things that turn out to be wrong, but that doesn’t make them a liar, mentally, it just means they made a mistake.

"We don’t want journalists to be lawyers, but we want them to know when the alarm bells are ringing and to know when they have to talk to a lawyer."

So using different words, instead of saying that someone is a liar, but saying, ‘They said this, and it’s not right’ just gives you a little more flexibility. Because if you’re sued for calling someone a liar, you have to show a mental intent, and that can be really hard. We can make suggestions like that, to maybe make things safer to publish, and we work with journalists to do that.

We also deal with complaints afterwards — that’s the second main part.

Another thing that has changed enormously is that we used to just look at defamation and a bit of copyright; nowadays we look a lot at privacy and data protection, which are big new problems. When I started it was mainly print, whereas now with online there is so much volume that you can’t possibly lawyer everything that goes up online so we need to do more training of journalists, to make them aware of the problem areas. We don’t want journalists to be lawyers, but we want them to know when the alarm bells are ringing and to know when they have to talk to a lawyer, and to talk to a lawyer early.

On stories like Snowden, or the big data stories, there’s not a lot that we can input early in those processes, but we can have conversations about public interest, and where public interest generally lies. But we can be with the journalists all the way on that journey, right the way up to publication, available for them to chat to, to look at stories as they start being written, as drafts start coming out and saying, ‘Well that’s really tricky, maybe we need to look at different areas.’

And one of the great things about dialogues between lawyers and journalists — or should be — is that the lawyer can say, ‘This is what my concern is,’ and good journalists can listen to that and do what they want to do but solve the legal problem, so you work together trying to tease out these things and find a safe route through them.

There aren’t many of us; we are about 30-40 media lawyers in Britain, still a relatively small number of people.

Photo: Majlinda Hoxha / K2.0.

Some deputies here in Kosovo are planning to propose a law that will stop journalists from publishing classified information, which is intended to ‘regulate media reporting.’ The media and other experts consider it to be more for media censorship, to discipline media reporting, particularly of online news sites. What are your thoughts on this, on the interaction of the law with media regulation?.

I think there’s a tendency everywhere for states to be worried about their official information, and that goes back to Snowden and data leaks. Governments are too paranoid about what they’re doing and saying, and it being made known; they over-classify too much data. If they were less sensorial about classifying information in the first place, then there wouldn’t be all this secret data around.

In the UK and in Australia they are doing the same thing, using quasi-terror laws to say, ‘We need to have more powers over the press,’ and the fact that this is being discussed in Kosovo does not surprise me.

It’s a difficult climate. When it comes to terrorism, we understand why governments are worried and why they need to have proper powers — and it’s a balance. It just strikes me that they are trying to take too much on their side and not give enough back.

It’s not an easy question, because one of the things that came up in the UK in this discussion is that if you give the journalists some sort of protection and you have a public interest defence for journalists you build into this legislation, there are two big concerns about that: How do you define the public interest or when someone is acting in the public interest? Is that a journalist’s decision or a court decision?

"Part of democracy is that you get criticized, and you don’t always like what people say about you."

And the second question is: Who does it apply to? Who is a journalist? How do you define the people who get the benefits of these things? Does it apply to every single journalist who has ever written one blog, or do you narrow it, and where do you narrow it to?

So it’s one of those things that I think they go, ‘Yeah, we sort of understand where the problems are but it’s far too hard a problem for us, we don’t want to go there because if we have too wide a definition of journalist, that’s going to let the terrorist that posts a video online be protected, and we don’t want to get involved in difficult court cases on whether an ISIS video is speech.’

Those sorts of questions, governments are going, ‘It’s too difficult — it’s far easier to just go down this route,’ which is too sensorial. I think that’s a problem. Increasing regulation is also happening everywhere, because of what’s going on on the internet — nobody knows what to do with social media.

It’s a very complicated landscape, there are no easy answers. What you hope is — and there was a period of time when I thought this was happening — that governments were big enough and brave enough to say, ‘We can take criticism.’ You think, you should be OK about this — part of democracy is that you get criticized, and you don’t always like what people say about you.

Whistleblowing is still a relatively new concept. Institutions and others are still trying to figure out the consequences and the impact of whistleblowing. How did The Guardian deal with this new phenomenon at the beginning?

Generally, the journalist has the relationship with the whistleblower and not the editor. It’s for the individual journalist to take upon themselves the burden of source protection — it’s an ethical thing, not a legal thing — and that can be hard for both the journalist and the whistleblower.

The whistleblower is still working inside an organization and leaking under enormous pressure, and sometimes the only friend they’ve got is the journalist. That puts pressure on the journalist — ‘How much do I help the whistleblower?’ — and that’s complicated.

The European Court of Human Rights has recognized all sorts of protection for sources, but none of that really matters if states can work out who the source is because you’re careless as a journalist because you give too much [information].

Technologically as well, we leave trails everywhere these days, so going back to journalistic skills, journalists need to be very tech savvy. They need to communicate through safe channels, to talk to people on the streets, go back to old fashioned ways, not use email, not use Google Docs where even when you think you have deleted them they are still there.

Journalists rely a lot on whistleblowers. They’re a very important part in holding power to account, bringing out corruption, and it’s not an easy role.

"We got on a ferry across to a park and we walked around a concrete park for an hour and a half while he tells me what’s been going on."

The first one I remember specifically dealing with, I was working at The Times and Sunday Times, and along with four or five other papers they were just sent brown envelopes that arrived with some documents that led to the case that is known as Financial Times vs. The UK in Strasbourg, which were leaks about a merger of two South African breweries. The breweries wanted to find out who was leaking, and there was enormous pressure applied legally through the courts — all the newspapers were sued.

At one point there was the potential that The Guardian could have been made subject to a rolling daily fine, so each day you don’t tell us who the source is — 5,000 pounds. Commercially, that’s just a disaster.

So, nobody should enter into agreements with sources lightly. They should also be aware that it’s very easy for source protection to be subverted behind the scenes. Here is where more experienced journalists need to talk with less experienced journalists about how to deal with it and what problems may arise.

When I did the Edward Snowden thing I was in Australia at the time because The Guardian was opening the Australian office. I was due to fly back via Hong Kong and they said: “Actually, we would like you to stay a few days in Hong Kong, there’s something happening there and we’d like you to be involved in it.” I had no Hong Kong money, had never been there before and knew nothing.

I arrived in the middle of the night in this hotel and there was a knock on the door in the morning from Ewen MacAskill, the Guardian journalist, and he says: “Come on Gill, leave all your electronics behind, just don’t take them.” We got on a ferry across to a park and we walked around a concrete park for an hour and a half while he tells me what’s been going on. No trees, nothing, because they are paranoid about every possible listening device, anybody overhearing, and sometimes you have to go back to just talking to people verbally.

Was it worth it everything that you and the team did?

It has absolutely been worth it, although some were accused of being traitors, and there was an enormous amount of pressure on The Guardian politically, being accused of being a treacherous organization, of being a terrorist organization… it’s got to be better out than in, letting the sunlight in. But people don’t like it.

There was a huge amount of criticism from the government that we put people at risk — there was never any evidence of that, we were extraordinary careful about that. We chose stories that were embarrassing to the government, that exposed all those problems that we’ve been talking about, not stories that showed where spies were located.

During the presidential elections in the U.S., when Trump became president, a city in Macedonia, Veles, was revealed to be one of the main sources of fake news. How can this phenomenon of fake news be dealt with, and what’s the difference between fake news and propaganda?

I think the answer is that the number one ethical thing for journalists must be to tell the truth. But the truth is a not an easy concept and it’s not two dimensional. It can be quite subjective.

For example, how many people died in the bombing in Dresden [in World War II] is still open to argument because it is hard to verify. That doesn’t mean that you get all the things right, you make mistakes, but you have tried your best and this is a moving process.

Fake news is deliberately putting out falsities, and this is a big difference and it comes down to trust. I’m not very impressed by anonymous journalism. If you are going to say something, put your name to it. There are risks, but we discussed that and that is the way to hold yourself accountable.

"It’s not just hearing it and reporting, it’s sending someone over there to interview people and finding out what did go on."

Another area that creates difficulties is around opinion, because that’s not fact and not news. It’s people giving their own personal views based on certain events and they can say quite extreme things on the basis of a set of facts — and it’s not necessarily fake news. Steve Bannon can express quite extreme views and a lot of it isn’t fake, a lot of what Trump says isn’t fake — it’s just his opinion, which is quite extreme.

On social media, there have been numerous cases of people saying things, misreporting, rumors, and they spread, despite there being no basis in them. The internet is an echo-chamber. So what proper newspapers should be doing is taking those stories, stopping, not publishing, and going and checking them. It’s not just hearing it and reporting, it’s sending someone over there to interview people and finding out what did go on. There’s still a physical element to journalism.

We had a very small data leak by a local authority on the back of the Grenfell Tower disaster [in which a tower block in London burnt down in 2017]. Kensington and Chelsea Council accidentally leaked information about the number of vacant properties that were in a place where people [who had been living in the tower] were going to be rehoused.

We could have just published that database but we sent a journalist out to knock on doors, and it turned out that these records were not right. We only found out that the leaked records weren’t true because people would come out of their places in their pajamas and say that they had been living there for more than 20 years.

Propaganda may be true, but it’s spin, and it’s usually put out by governments or commercial interests. It’s what [journalist and author] Nick Davies called ‘churnalism.’ You have got to stop and you’ve got to ask questions.K

This conversation has been edited for length and clarity. The interview was conducted in English.

Feature image: Majlinda Hoxha / K2.0.