Not far from the center of Tirana, on the opposite side of the road from where the Orthodox cathedral stands today, the pallid contour of an old building can just about be discerned. The abundant leaves of an ivy have surrounded the second-floor windows and left traces of green on the red bricks that make up the decorative balconies.

This building, for a long time known as “The House of Leaves,” has taken on a new function today: the former headquarters of the ‘Sigurimi’ — the state security, intelligence and secret police service of Albania under Enver Hoxha’s totalitarian communist dictatorship — has now become a museum. In June, its newly appointed director met me in the leafy courtyard, and showed me around.

Along the narrow corridors, on both floors of the house, the doors of the rooms are open. A weak illumination exposes unknown objects… and then, suddenly, a painting appears where a window should be. It’s a piece by Edison Gjergo, a formerly convicted painter who spent eight years imprisoned after being arrested by the Sigurimi. The victim and the hangman were now together, both under the same roof.

After being used by the gestapo during World War II, the House of Leaves then became a security office used for investigations by Sigurimi. Photo: Artan Rama.

Of course, it is not by chance. I knew the painting, “The Epic of the Morning Stars” — the magical blue of its dramatic background and the white beard of the rhapsodist shadowed the group of partisans. It is an “Epic” that marked the rise and fall of its author, leading to his arrest. Underneath the painting, in a display case, was placed file number 6095.

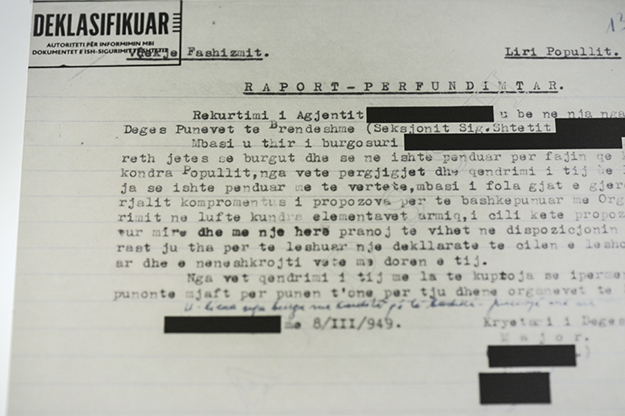

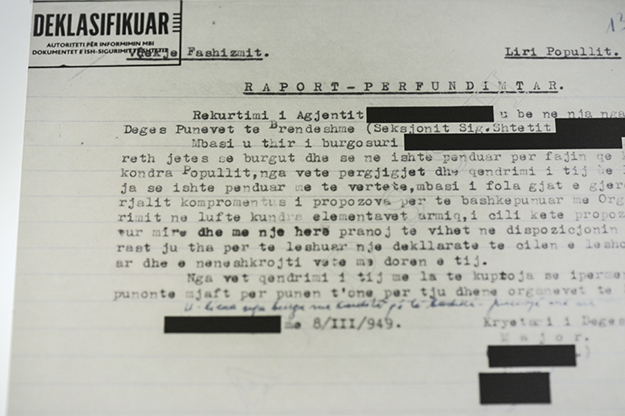

The advice in file number 6095

The Sigurimi’s operational data, cleared of dust, are now exposed to the public for the first time, but the names are missing. The names of the operatives, the names of the collaborators, and the names of the investigators are all deleted by a smear of black ink. In their place are pseudonyms: “Big cupboard,” “The Artist,” “Fatmiri,” “The Plan,” “The Stick.” Agents and secret informants are still hiding behind the black stains.

I look closely at the documents, and read… “Edison! You must forget what your taste is — and what good taste is! We have to work on what the taste of everyone is.” It was a piece of ‘advice’ from the Secretary of the Writers’ League, reported on by secret agent “Big cupboard.”

Operational file number 6095 contains 148 reports in total, dozens of them provided by “Big cupboard.” Another document reads: “The source reports that he has gone several times to meet Edison Gjergo in his studio, and on July 1, 1974, at around 19:00, found him together with his fiancee…”

I ask the director whether they knew that Edison had been engaged. She shook her head, smiled politely and said that the selection committee did not deal with private affairs — according to her, the museum was interested in the phenomenon and not the names. Then she added suddenly: “But down at the exit, a lady left a note in the visitor’s book… she said she was his fiancee.”

The idea that a person mentioned in the file had come to the museum and moreover, the fiancee herself, pricked at my curiosity. I went downstairs and leafed through the book, starting from the back. This is what I found:

“I am a victim of these terrible interceptions, they destroyed my life’s dream. I was engaged to Edison in May 1974 until he was arrested in January 1975. Edison remains unforgettable in my heart.”

A phone number was left at the bottom. I called her and fixed a meeting.

We met two days later in a quiet cafe. The lady in front of me had a portrait that conveyed a warm color. I took out my notebook and jotted down everything I heard.

“I first met Edison when he was at a mature age, and with clear views about life,” she told me. “I did not manage to know his early youth, but his artistic maturity, yes. I studied architecture, while he was an extraordinary artist. He could create plans and volumes by colors.” She spoke slowly, and in short sentences, but also freely, and with a timid longing hidden behind every word she said, so much so that I was afraid to break it.

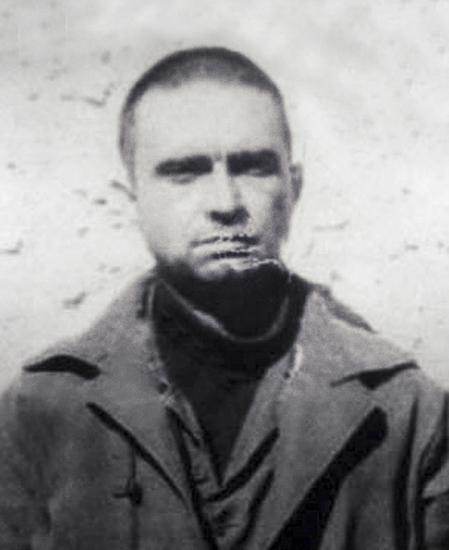

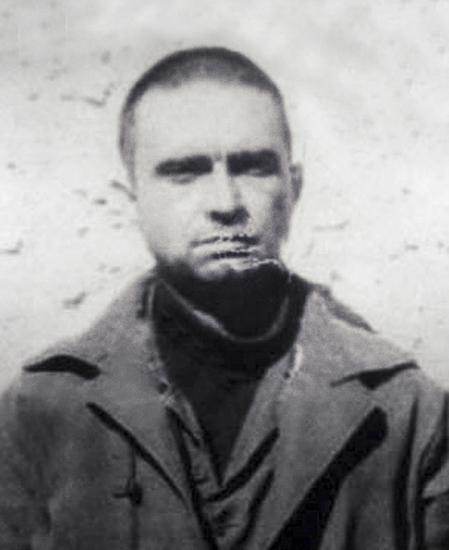

Edison Gjergo in his first year of detention, after being arrested in Jan. 1975 on account of his “The Epic of the Morning Stars” having a “pessimistic outlook.” Photo: Artan Rama.

Seven months of love

“Once he made a portrait of me. I posed for three sessions. We were at the studio and suddenly he ordered me to lie down on the couch. ‘Find a comfortable position and hold your hand up, like this… You will have to stay like that for a few hours,’ he told me. The portrait was a miracle. It was in Modigliani’s style,” she paused and looked at me.

“Were you together when he composed the Epic?” I asked.

“No, he had just finished it when we became acquainted,” she replied, full of certainty, before continuing the narration:

“We stayed together seven months. On January 2, 1975, we got engaged and it was wonderful. They arrested him two weeks later. It was 7:30 in the morning. They got him from the bed. He was in his pajamas when they took him. Then they asked me to hand over the key to Edison’s studio. When I went to the Writers’ League at noon, the secretary came out onto the stairs and said to me: ‘Edison is an enemy of the people and the party!’ He took the key and went inside. My entire world was in that key.”

Silence followed. It was unclear to me whether I should continue to ask questions. The woman looked outside, but it seemed to me she was looking elsewhere. We were both immersed in the past of a man with no future, though with an extraordinary talent. I recalled his words written in one of the declassified facsimiles: “I am in a state of constant boredom. Not only me, my friends feel the same. No one says a word of joy. Even when it seems that a new life begins, conditions and circumstances are immediately created to suffocate it.”

The quote was part of a piece of information that “Big cupboard” reported to the operational officer several months before Edison was arrested. I tried to imagine what hope his engagement to the then 24-year-old architecture student might have given the painter, what power she might have given to his art.

The Sigurimi’s reports on their targets are now available to the public, though the names are redacted. Photo: Artan Rama.

I asked her what had happened next. She breathed deeply and thought a little. More than 40 years had passed, but her memory was still fresh.

“I met secretly with Edison’s mother in his aunt’s house,” she began. “It was not easy for her either. Edison needed clothes and food in prison. So one day I collected our engagement gifts and handed them over to Kornelia — that was his mother’s name. I told her: ‘You can sell these.’ She did not accept them, but I insisted. ‘Take them because you have a lot of expenses,’ I said. ‘And Edison is in need of the money.’ I gave them to her again. She became silent and her eyes filled with tears. We continued to meet in this way for five years. I communicated with Edison through her, using codes. But he became more silent as time passed. We met less and his mother said that it was for my benefit, that he himself was demanding it from prison. He wanted to protect me.”

Suddenly the woman stopped, but I kept writing. My thoughts flew far away, into the cells of Spac, where the prisoner had protected the only good thing he had received from this life by driving her away, by giving her an opportunity to continue.

Love beyond measure

“Did you meet afterwards… when he was released?” I specified.

“No. Never. When he got out of prison I was still unmarried. But he never approached me. It was a terrible time. He knew he was being followed by the Sigurimi. Then he married. We both got married, with others. My husband is a good man, but I kept this story inside. Edison loved me beyond measure, he respected me, and I had an extraordinary impact on him. I had a premonition on the day that he died. I was sluggish and tired. A friend of mine told me the news. I’d finished my work and was returning home. On my way, somewhere near the center, a bus stopped. I recognized someone among the people when they were getting off. It was the bus that came back from the cemetery. It was the only one. I mourned for a whole month, and it became noticeable.”

The woman paused and looked at me. Maybe she expected me to say something, but I felt powerless. Then she withdrew and searched in her bag. I had many questions, but I chose to keep silent. I started to think of one of the declassified papers in the museum dated September 8, 1989. It read: “The operational processing file 2B was archived at Section IV, because the target had died.” Edison Gjergo died of acute pancreatic inflammation at Tirana Hospital in the summer of 1989, so, paradoxically, surveillance was only officially terminated a few months after his death.

“What about the portrait, what happened to it … you sitting on the couch?” I dared to ask.

“It was not found! Everything was confiscated by the Sigurimi. I made a request once to the Ministry of Internal Affairs. I did not get a reply. It seems as though it has been stolen,” she concluded, and remained silent for a while. “I only have the engagement ring from him, which he made himself. But in one of his paintings, there are some girls working at a factory. I am one of them, he drew my portrait.”

“Have you been able to move on?,” I asked.

“It’s a pain and a blessing to experience it. Life takes you away. You have a sort of desire that keeps you alive, but when it is not realized until the end, it is a great, permanent pain. The only things I have gained are my two children, my daughter, and my son who is a talented sculptor.”

I closed my notebook. I had an excitement and a sense of guilt within myself.

“I have a last question. What impression did the Museum leave on you?”

She thought and did not move for a while.

“I saw there the mirror of vanity that took a man’s life. I saw the evidence of hate and ambition… an entire list of people against him! That is why I wanted to speak out against the rascals who harmed Edison, who followed and testified against him when he was at his peak, when we were in love. But they had hidden the names! It’s good not to hide the names.”

Sigurimi had the most modern technology available to conduct their activities, including equipment imported from Germany, Russia, Japan and China. Photo: Artan Rama.

Three hours had passed as she told me this sad story but on leaving, I knew exactly what I had to do. It only took me a few days to find the names of the Sigurimi informants and officers involved in Edison’s case.

I still had to make a final verification, so I went back to the “House of Leaves.” The excitement had passed, and the sense of inexplicable guilt had been replaced by an inner belief. I had fixed a meeting with Edison’s fiancee, but this time I would do most of the talking. She should know. She should learn, who the zealous agent, this “Big cupboard,” was, who the real names covered in black were; whether they were alive, whether they were indemnified as former persecuted people, whether they had received a supplementary pension as retired military. Oh, how many things she would learn. I had no dilemma anymore. Silence helps the guilty and not the victims.

A light breeze blew on the square in front of the house. The leaves rose noiselessly and dropped again softly. In the courtyard covered with leaves containing the facades with decorative balconies, behind which the former Sigurimi secrets were kept, everything seemed peaceful.

Feature image: Artan Rama.