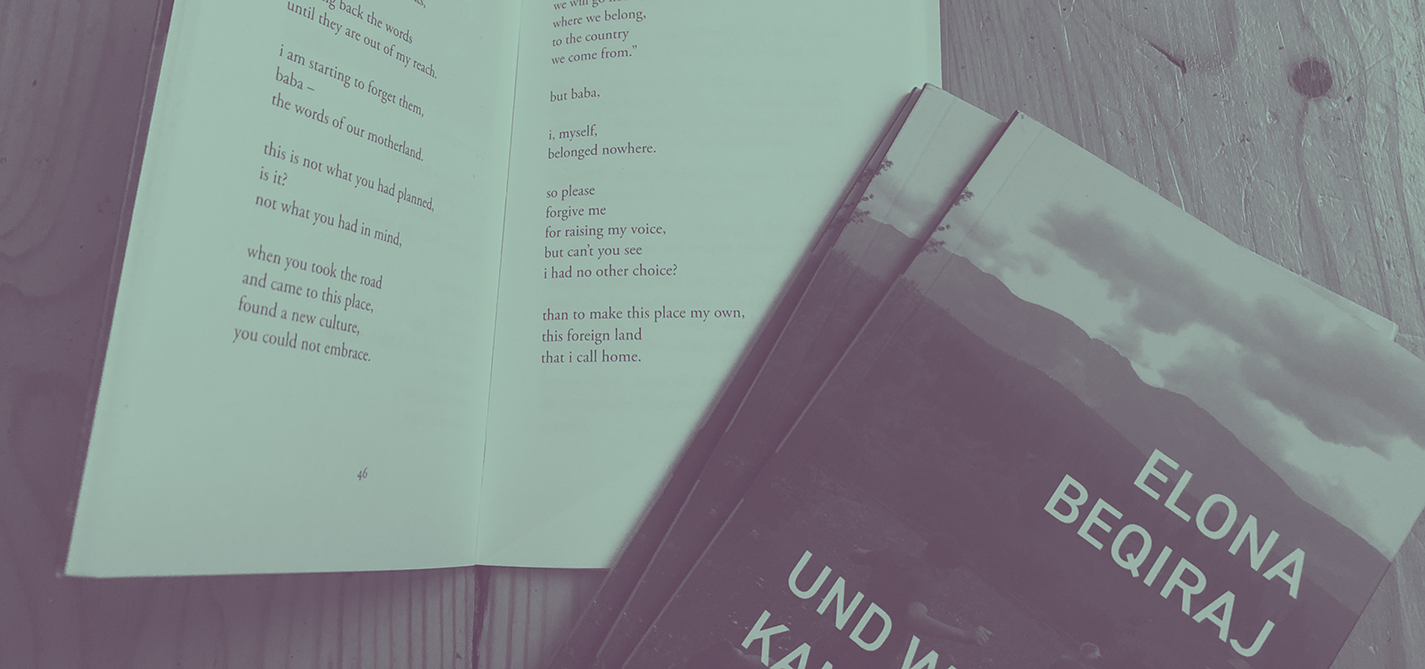

Elona Beqiraj: Today, I decide not to decide and live my hybrid identity

The poet and photographer talks about the consequences of migration and finding her place.

I waited all year to come to Kosovo in the summer and when I was there, I realized how differently I was viewed by the Albanians.

A part of my identity was being taken away every time Germans acted as if it is so hard to pronounce my name but then they know how to pronounce every "Game of Thrones" character’s name.

Edona Kryeziu

Edona Kryeziu was a journalist covering Arts & Culture at K2.0. She holds a Bachelor of Arts from Maastricht University, the Netherlands, and a Masters Degree in Migration & Diaspora Studies (Visual Anthropology) from SOAS London University, UK.

This story was originally written in English.